HISTORY LESSON: Paper Lion and the birth of modern NFL media

Before Hard Knocks, there was Paper Lion — George Plimpton’s wild Lions experiment that made football a content machine.

Welcome to History Lesson, a recurring feature in Model D led by local historian Jacob Jones, in which we delve deep into the annals of Detroit history and nerd out over a different topic each time. This month, we’re talking about how George Plimpton gave fans unfiltered access to the NFL, long before Hard Knocks and Netflix.

Football content has become inescapable. Hard Knocks is decades old. Streaming platforms pump out multi-episode series about quarterbacks and wide receivers. Glossy behind-the-scenes documentaries spotlight Notre Dame football. A new hagiography about the Kansas City Chiefs just dropped on ESPN, and their star tight end made national headlines for getting engaged to the world’s biggest pop star. If you’re anything like me, you’ve spent the last couple of weeks scrolling through the hilarious U-40 adult football clips on TikTok.

Football is no longer just a sport. It’s a genre all its own. The NFL, more than any other league, has transformed into a content machine. But that machine wasn’t first built by a TV network, a glossy sports magazine, or a billionaire team owner. It was sparked by a patrician New York writer who simply wanted to see what it was like to play quarterback.

That writer was George Plimpton. Born in 1927, raised in New York privilege, and educated at Harvard and Cambridge, Plimpton was one of America’s literary stars. If you missed his heyday, you may know him from Ken Burns’ Baseball or as one of the therapists Matt Damon outsmarts in Good Will Hunting. Plimpton built his career on “participatory journalism.” He boxed with Archie Moore, played percussion with the New York Philharmonic, and even tried out for the Boston Bruins. But it was his foray into football that became his most influential stunt.

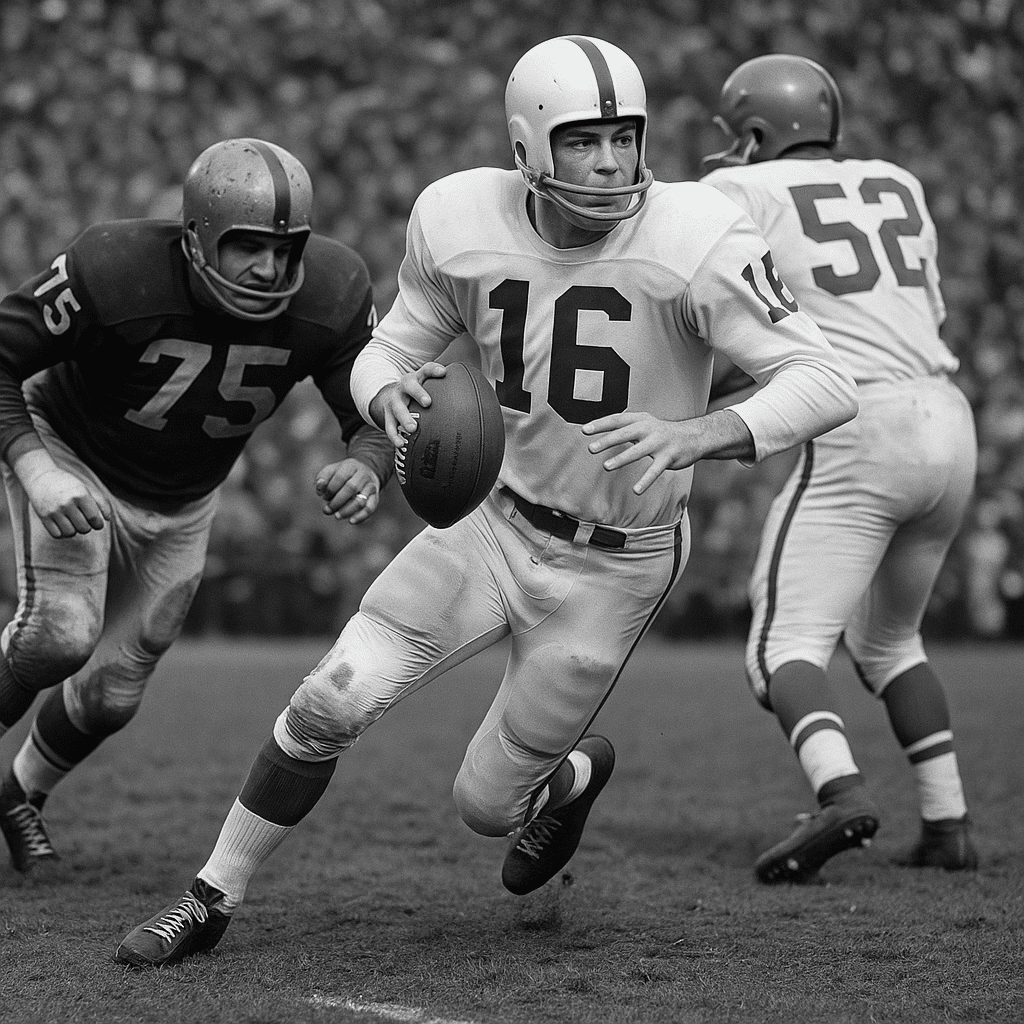

In 1963, Plimpton brought that approach to Detroit. The Lions gave him unfiltered access to training camp. His goal: see if a regular man, however smart, could survive in the NFL. What came out of that experiment was Paper Lion, a book that changed how America thought about football and, arguably, how the NFL thought about itself.

The Lions of the early ’60s were in transition. The suspension of Alex Karras, the face of the franchise, revealed just how human football heroes could be. The rest of the roster were blue-collar grinders; tough, industrious, unflashy. An extension of Detroit itself. Plimpton, on the other hand, was a gangly, patrician, New England aristocrat. Yet Cranbrook, the prep school that hosted the Lions’ training camp, was probably more familiar to him than to the rugged players.

Plimpton’s experiment was unsuccessful on the field. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle banned him from playing in a real game, so his only snaps came during the Lions’ intra-squad scrimmage in Pontiac. He took five snaps and lost yardage on each. But the access he provided fans was revolutionary.

Plimpton’s ineptitude wasn’t what made Paper Lion compelling; it was the way the Lions embraced, teased, and protected him. Readers got an unprecedented look into football culture: the banter, rituals, camaraderie, and constant undercurrent of violence. Plimpton showed fans the conversations in the huddle, rookies’ struggles, egotistical receivers, punchy offensive linemen, the work of equipment managers, and the monotony of daily practice. Fans wanted the messy, human side of the NFL as much as the highlights, and Plimpton delivered.

One major difference from today: the team had no editorial oversight. Plimpton included stories of autograph-obsessed players, prima donna wide receivers, hard-partying and gambling Karras, and crude sideline commentary about teenage fans. Today, teams and players tightly control their image. Even Hard Knocks has become a puff piece, and with the NFL owning a stake in ESPN, real journalism is rarer. Plimpton’s Lions were unvarnished.

In many ways, Paper Lion anticipated everything from Hard Knocks to Netflix’s Quarterback. Mic’d-up Jared Goff or Amon-Ra St. Brown jawing on the sidelines, rookies breaking down during cuts, these are all descendants of Plimpton. He even hosted the Lions’ rookie talent show and sang his school’s fight song, now a late-summer NFL media staple today.

Plimpton also introduced the concept of player-owned media. Long before Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube, he was the ultimate “player-forward” experiment. Not a real NFL player, he embedded himself in camp and became a living lens for fans. He included stories that would be impossible today: wide receivers intentionally removing helmets for fan attention, offensive linemen making crude remarks about teenage girls on the sideline, and coaches sharing unfiltered opinions about players on other teams. Modern teams carefully manage every word, every camera angle, every social media post, but Plimpton’s Lions were unvarnished.

The connection between past and present is uncanny. Plimpton recalls All-Pro wide receiver Gail Cogdill sprawled on the training table during a game, seemingly to separate himself from the sideline crowd and catch the fans’ eyes. Fast-forward six decades, and you see Micah Parsons, Cowboys All-Pro defensive end, lying on the sideline training table mid-game, apparently napping, fully aware the cameras and fans are watching.

Cheeky or self-conscious, it’s undeniably performative, echoing the same human vulnerability and fan access Plimpton captured in Detroit. The NFL content machine has grown exponentially since then, but the DNA is the same: intimacy, humor, humanity, and the way moments off the field can become as memorable as those on it, and it all started here in Detroit.