HISTORY LESSON: The significance of the Palmer Park Historic District

Palmer Park’s 57 apartment buildings represent one of Detroit’s clearest examples of intentional, high-quality multifamily planning.

Six miles north of Campus Martius, closer to suburban Ferndale than it is to the city’s central business district, sits the Palmer Park Historic District, built during Detroit’s automotive boom years, when single-family neighborhoods were popping up all over the city. Arguably, the most distinct residential district in the city, the collection of apartments offered a different vision for Detroit’s growth. A dense, elegant community of multi-family buildings built for urban life rather than suburban sprawl

That alternative vision now stands at risk. Aaron Mondry’s recent Outlier Media investigation, “Arizona investors bought up a historic Detroit neighborhood — then left it in ruins,” details how a speculative real estate gamble has left nearly a third of Palmer Park’s apartment buildings abandoned, stripped of wiring and plumbing, scarred by fire damage, or trapped in foreclosure and receivership. County auctions for some properties drew no bidders. Inspection reports describe buildings so deteriorated that returning them to livable condition will require massive investment.

But the crisis unfolding in Palmer Park is not merely a story of mismanagement and housing instability. It represents an existential threat to one of Detroit’s most unique and ambitious residential communities, a dense, architecturally rich apartment district that once offered a cosmopolitan alternative to the city’s dominant landscape of single-family homes.

Detroit is not without preservation victories. The Book Tower, Michigan Central Station, and countless grand mansions in Boston Edison, Indian Village, and Brush Park have been saved through vision and investment. These landmarks rightly command attention and resources. But it has proven a far easier task to elicit the investment required to restore grandiose buildings of commerce and enviable single-family estates than it has for the dense, multifamily communal living that once was commonplace in historic urban life. The Palmer Park Apartment Building Historic District stands as one of the clearest expressions of the high-quality, dense craftsmanship that has been forgotten in modern development.

A cosmopolitan oasis in a city of homes

Detroit’s physical identity was forged through the single-family house. In the midst of Detroit’s roaring twenties boom, houses were springing up all across the landscape. In 1925 alone, nearly 12,000 permits were issued for single-family homes, cementing low-density development as the city’s dominant pattern.

The Palmer Park Historic District presented a deliberate break from that pattern. The neighborhood featured landscaped courtyards, gently curving streets, and planning concepts inspired by English New Town communities, all designed to support walkable, community-oriented living. Its close proximity to Palmer Park and the Detroit Golf Club gave it a feel of country elegance while preserving its urbaneness. It demonstrated that you didn’t have to be in a Boston-Edison mansion or a downtown high-rise hotel to live a refined life.

Detroit’s most exotic architectural experiment

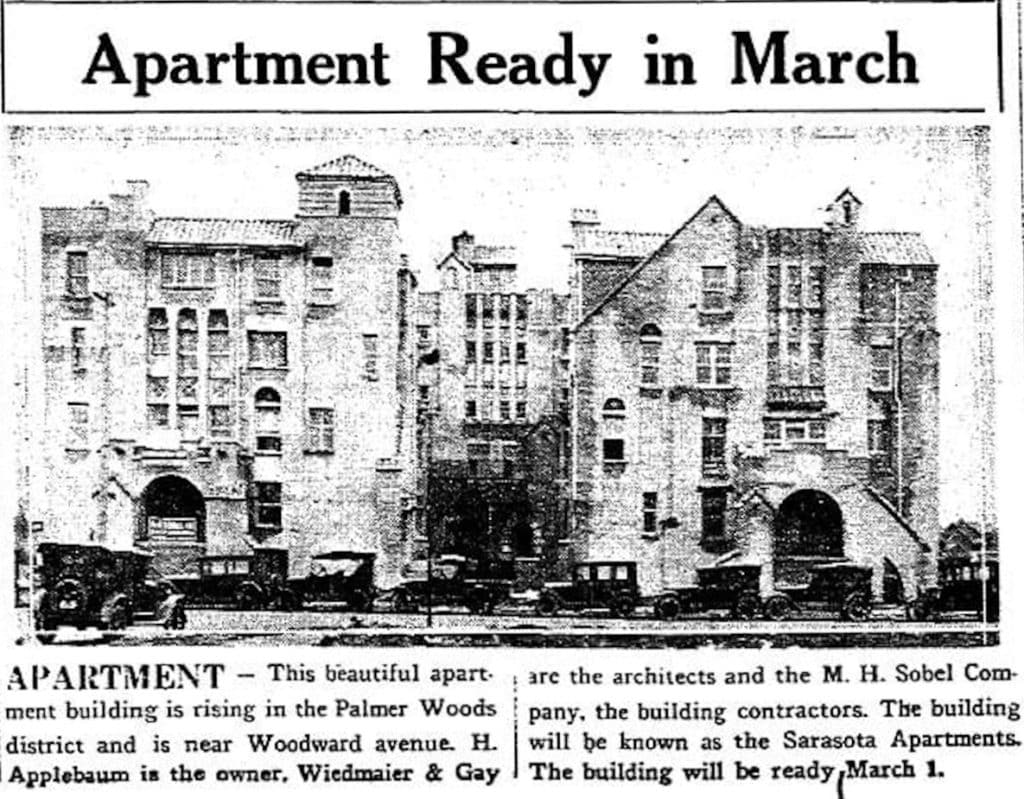

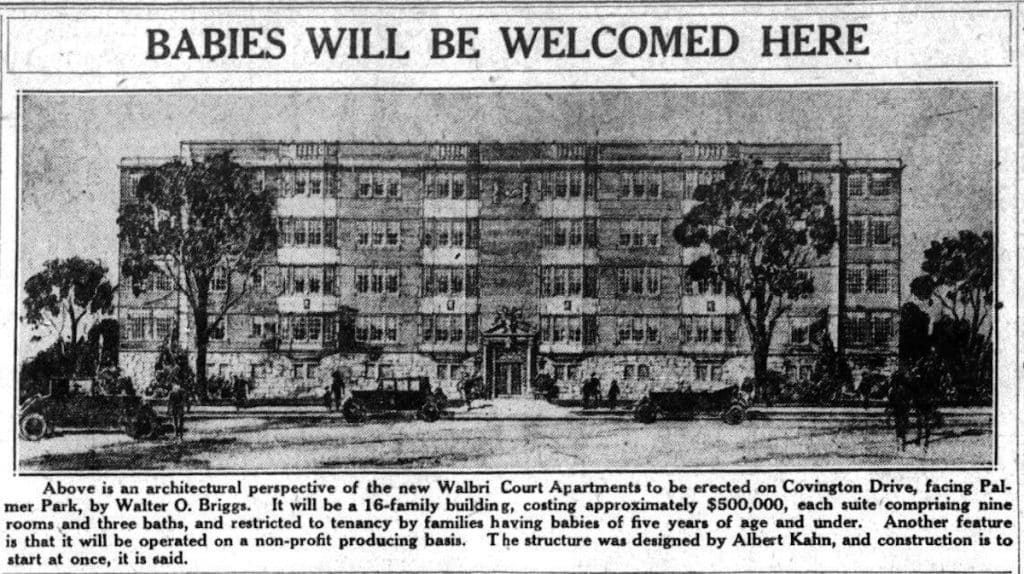

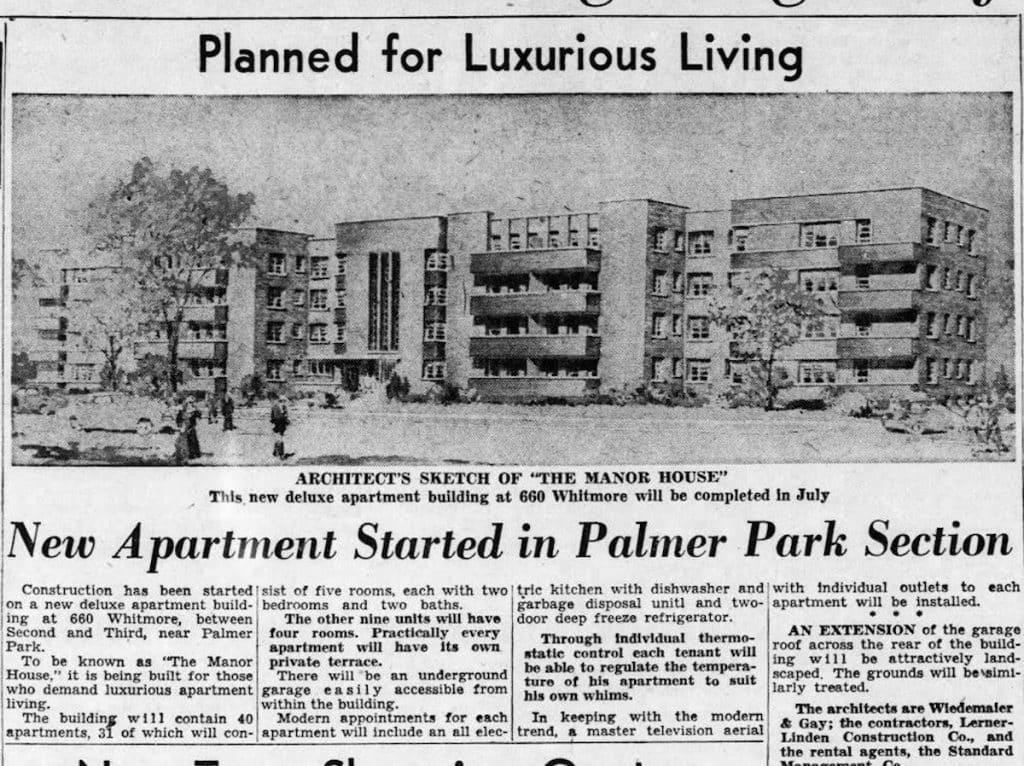

Formal development began in 1925 with the Walbri Court Apartments by Albert Kahn. Over the following decades, leading architects such as Robert West, William Kapp, and Weidmaier and Gay transformed Palmer Park into one of Detroit’s most architecturally diverse residential districts.

Rather than repeating the city’s typical brick forms, the neighborhood embraced a striking mix of global influences: Egyptian motifs, Moorish Revival arches, Venetian detailing, Spanish Colonial elements, and Tudor-inspired structures — all within a compact, walkable area.

Architectural innovation continued into the mid-20th century. The Balmoral Apartments of 1937 introduced corner casement windows to maximize light and airflow. The Covington Arms, completed in 1953, reflected modernist design principles and became one of Detroit’s earliest luxury cooperative apartment buildings.

Together, these structures elevated multifamily housing to the level of architectural expression usually reserved for civic buildings and elite residences.

A neighborhood with a social soul

The district’s density fostered a strong community life. In the 1930s and 1940s, Palmer Park became a major center of Detroit’s Jewish population as families moved northwest from older neighborhoods. Religious and cultural institutions anchored daily life and reinforced the neighborhood’s role as a thriving urban enclave.

By the 1970s, the area evolved again, emerging as the heart of Detroit’s LGBTQ community. A network of gay-owned bars, bookstores, and restaurants transformed Palmer Park into one of the city’s most visible and vibrant cultural districts.

Why preservation must be vigorous

The significance of Palmer Park’s Apartments lies in the collective urban landscape they form. Its 57 apartment buildings represent one of Detroit’s clearest examples of intentional, high-quality multifamily planning — a neighborhood designed around density, walkability, and architectural ambition that brought a different type of urban living to Detroit’s residential neighborhoods.

But as vacancy and deterioration spread, the district’s historic integrity weakens building by building. When infrastructure is stripped, neglect takes hold, and when structures are emptied, the damage compounds, making restoration more difficult and eroding the sense of place that gives historic districts their meaning.

At the same time, Detroit, like cities across the country, is confronting rising housing costs and a growing need for stable, attainable places to live. Multifamily housing has long been one of the most effective tools for meeting that need. Apartment communities allow more people to live near jobs, transit, parks, and services while reducing infrastructure costs and supporting walkable neighborhoods. Historically, districts like Palmer Park offered middle-class housing that balanced density with quality, proving that urban living could be both affordable and dignified.

Preserving these buildings, then, is not simply an act of historical stewardship. It is an investment in housing forms that have consistently supported economic and architectural diversity, community life, and urban sustainability.

Detroit’s powerbrokers have often privileged monumental architectural preservation over that of everyday urban housing. Yet apartment communities like Palmer Park tell essential stories about the city’s growth and design sensibilities while offering real lessons for addressing today’s housing pressures.

If preservation is truly about protecting the city’s full history and preparing for its future, then multifamily districts like Palmer Park deserve the same urgency and investment as our most celebrated landmarks.

History Lesson is a recurring feature in Model D led by local historian Jacob Jones, in which we delve deep into the annals of Detroit history.