HISTORY LESSON: At Detroit’s first Thanksgiving, gratitude was about being alive

During the second half of the 19th century, Thanksgiving traditions in America varied from region to region. Michigan’s observance began in 1834.

Ninety years before Detroit’s first Hudson’s Parade, a century before the Lions first took the gridiron on Thanksgiving, and three years before Michigan became a state, the city of Detroit paused for its very first Thanksgiving.

But the holiday was not the waistline-expanding familial celebration that we know today. It was more of a thank you from the living that they weren’t one of the hundreds who died in the long hot summer of 1834.

Only weeks earlier, a terrifying wave of cholera swept through the city, claiming as much as 10 percent of the population. When the crisis finally broke with the arrival of cold weather, 23-year-old acting territorial governor Stevens T. Mason declared Thursday Nov. 27 a day of thanksgiving. He urged the residents to pause, pray, and acknowledge what they had endured.

Pumps, wells, and buckets

In 1834, Detroit was a small but growing frontier metropolis. Less than 30 years removed from the Great Fire of 1805, Detroit’s population was in the process of growing by more than 300% in a decade. Spurred by the opening of the Erie Canal, which connected the Great Lakes to the East Coast, waves of migrants from around the world, including New England and New York, poured into the city, helping to transform it from a Western outpost into a 19th-century boomtown. But the rapid growth of Detroit severely outpaced its infrastructure, especially when it came to water and sanitation.

The City’s water system was still little more than pumps, wells, and buckets. Most residents relied on shallow public or private wells, the Detroit River, or the small rivers and streams that used to run through the city. There was no proper sewer system, no filtration, and almost no thought given to the proper way to dispose of wastewater. Two years shy of any real effort to build waterworks in Detroit and over 30 years from any real successful filtration system, the Detroit water system was primed for a waterborne disease to thrive.

Cholera is caused by bacteria that flourish in warm, contaminated water. It doesn’t spread person-to-person, but through ingesting water tainted with human waste. In a city water system based on shallow wells and poor drainage, it can move quickly.

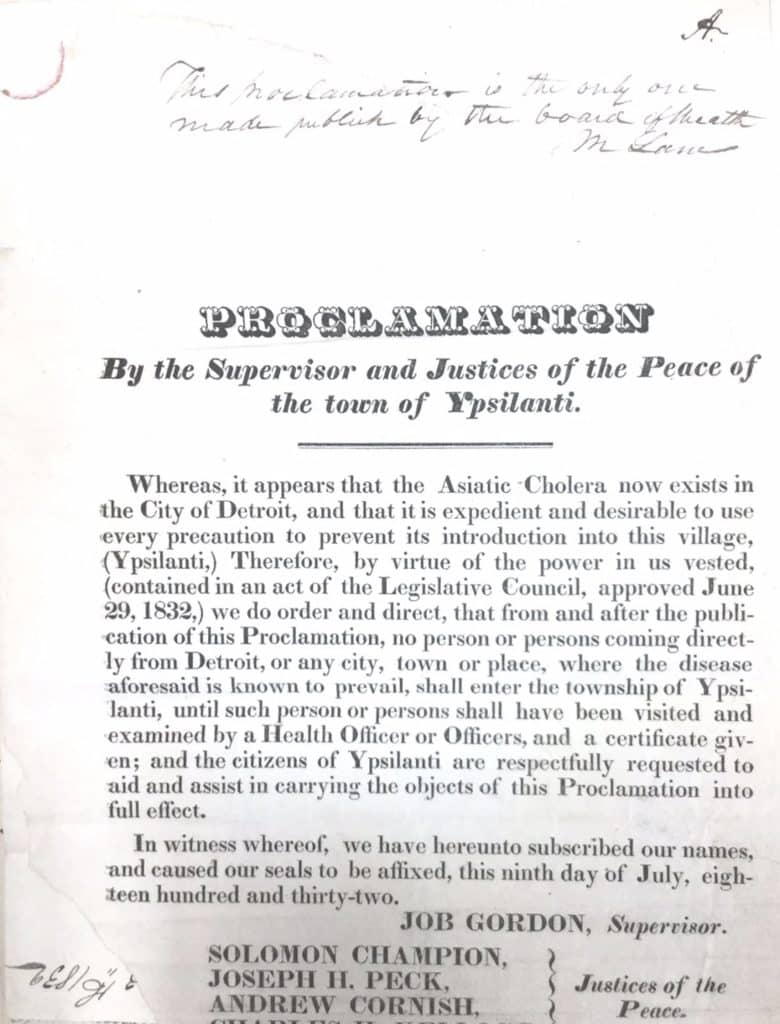

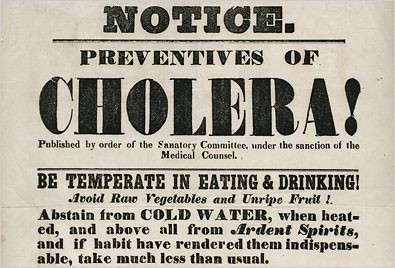

Cholera first hit Detroit in 1832 and it terrified Detroiters. In turn, the city took some precautions. Officials ordered that streets be swept and garbage removed. Pools of standing water were drained. Residents were ordered to purify their houses. But many attempted to flee the city. Usually unsuccessfully. As far away as Monroe, towns and villages began banning Detroiters from their borders. None took greater steps than Ypsilanti, who sent armed men to the roads leading into town. At one point, a group of deputized Ypsilanti residents shot at a postal worker, killing his horse, and committing a federal crime in the process.

Panic spreads

Without an understanding of germs, residents blamed bad air, summer heat, immigrants, the poor, or moral failings. But as neighbors began collapsing from violent dehydration and seemingly unable to leave, the panic began to spread around them.

An eerie death notice began to pass through the city. Traditionally, in Detroit, church bells rang out when a parishioner died. But as the disease spread, the bells began ringing again and again and again. On the worst day, a reported 16 Detroiters died, and one can only imagine the sheer terror that those bells brought across the city.

Eventually, the churches agreed to stop the ringing. By the time they resumed, at the end of September, more than 700 Detroiters had fallen ill with cholera and upwards of 10% of the City’s population had died.

Cholera and the terror it created would be ushered out along with the hot summer air that it thrived in. For many Detroiters, especially the newcomers from New York and New England, the moment seemed to naturally call for the kind of civic pause that had occurred back home.

Giving thanks

In the early 1800s, governors across New England regularly declared special days of Thanksgiving after fires, epidemics, droughts, or military victories. These observances were not the festive holiday season kickoff as we think of them today, but a collective moment of reflection and gratitude.

So, with Detroit, the seat of the Michigan territory still reeling from the outbreak, its acting Governor, Stevens T. Mason, proclaimed Thursday, Nov. 27, 1834, as a day of Thanksgiving and prayer:

…contemplating with reverence and resignation the dispensations of the Supreme Ruler of the Universe in the destructive pestilence that has visited our territory… we may present our prayers of gratitude for being permitted still to enjoy a participation in the blessings of his providence.”

Mason was known as the Boy Governor. He was just 23 years old when he issued this declaration. He had been appointed acting governor July 6, 1834, when he was 19, just as the cholera was multiplying in the city’s water supply.

Mason would go on to help bring Michigan from a territory into statehood, serving as our first governor. Although his life was brief — he died at just 31 — his influence on the state’s early identity was lasting. His 1834 proclamation wasn’t intended to launch a new tradition; it was just a practical approach to a difficult year and started Detroit’s a long line of Thanksgiving observances.

Today, Thanksgiving is one of our signature days. The parade and the Lions are broadcast into people’s homes across the country. For many, here and elsewhere, Detroit is synonymous with Thanksgiving. It is fitting that our first Thanksgiving came from a young leader trying to steady a struggling city. Mason couldn’t have imagined what Thanksgiving would become in Detroit — he helped create a tradition.

History Lesson is a recurring feature in Model D led by local historian Jacob Jones, in which we delve deep into the annals of Detroit history.