Changing lives from the very start: Report identifies best measures to help at-risk kids

More than half of Michigan's kids from birth to age 3 are at risk of showing up to kindergarten unprepared to learn. A new report outlines measures with the most evidence of success and highest return on investment to help them.

The 3-year-olds attending The Children’s Center‘s Head Start preschool program in Detroit are all giggles and smiles, exploring their surroundings with that special brand of bright eyes, innocence and curiosity that only toddlers possess.

These chubby-cheeked kids face big hurdles, though: poverty, parents with low educational attainment, parents who don’t speak English, developmental delays, disabilities or having a history of “toxic stress” from witnessing violence and trauma.

Statistically, kids with these problems are shown to be less likely to graduate high school and college, will earn less money as adults and are more likely to be incarcerated than kids from the general population.

But by their very presence in this Head Start program, these kids are receiving one of the interventions shown to reduce the risk of those outcomes.

That’s why funding for Head Start was boosted in 2013, with a $65 million funding infusion for the Great Start Readiness Program by the State of Michigan.

The boost focused on kids one year older than these ones, affording preschool to an additional 10,000 4-year-olds in the state. It represented the largest public preschool expansion in the nation but still left approximately 20,000 Michigan 4-year-olds unenrolled, according to an analysis by Bridge Magazine.

Early childhood advocates know birth to age 3 is a critical period for brain development, so they are increasingly turning their attention to that window of opportunity.

To be effective, they need to know two things. First, how many kids in Michigan are at risk? And second, which interventions have the best evidence of producing results?

“In public policy, we often invest in programs where we think the program works, but we don’t necessarily have a high-quality research study to know for sure,” says Jeff Guilfoyle, vice president at Public Sector Consultants, a Lansing-based public policy consultancy. “There’s a little bit of doing stuff on faith, and we need to have good, solid data to be able to help any population. There was a real knowledge gap on the number of at-risk children in Michigan and where Michigan should turn to next.”

To address this knowledge gap, PSC joined forces with Citizens Research Council of Michigan, a nonprofit public policy think tank, to answer these questions. Their report, Policy Options to Support Children from Birth to Age 3, was released late last year. The report was funded by a number of philanthropic organizations with an interest in early childhood education.

“We have significantly better evidence for early childhood programs than we do for the typical public program,” says Guilfoyle. “In this report, we use that evidence to outline the things policymakers should be considering if they want to tackle this issue. Compared to other things we frequently do in public policy, the evidence for early childhood investment is much more solid.”

What does the report tell us?

Childhood poverty in Michigan exceeds national average

Michigan’s poverty rate for kids in the age category birth to 5 exceeds the national average, according to 2013 American Community Survey data.

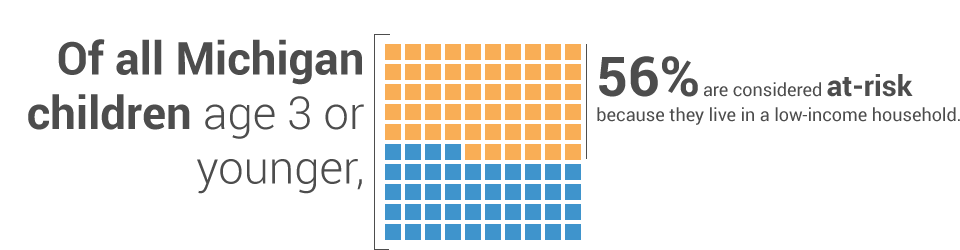

The PSC/CRC report found 56 percent of Michigan children from birth to age 3 —

260,000 kids — are considered to be at-risk for showing up to kindergarten unprepared for success, based on a family income threshold of 185 percent of the poverty line. This is the same threshold used to qualify families for reduced-price school lunches and Medicaid.

Making a difference through interventions

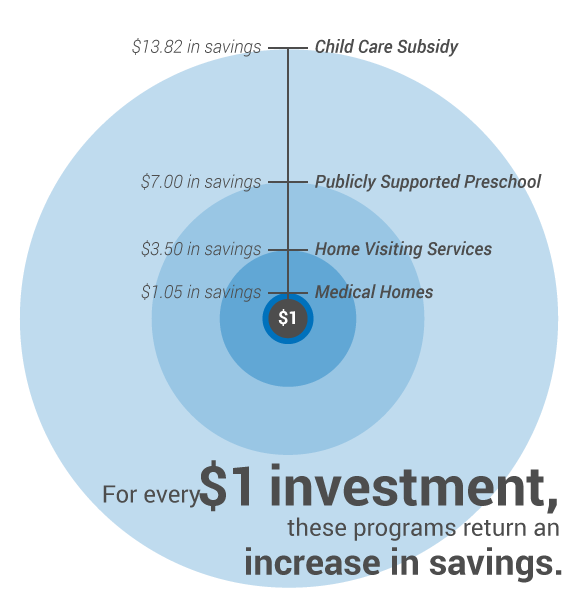

The PSC/CRC report identifies four interventions that have solid, research-based evidence of effectiveness and return on investment: home visiting programs, access to medical homes, high-quality child care and preschool for 3-year-olds.

“The programs we describe in this report have enough evidence behind them to warrant serious consideration by policy makers,” says Guilfoyle. “We looked at programs that were evidence-based, and paid a return on the investment. These would be a logical place for Michigan to go to next.”

Home visiting leads interventions

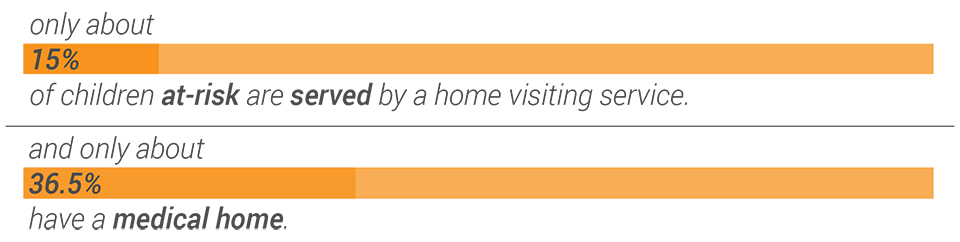

Of the four areas, evidence for home visiting programs is strongest, according to Guilfoyle.

“The evidence is fairly overwhelming,” he says. “We’re clearly not the only people who recognize this; the federal government is investing in these programs. They have some of the best evidence I’ve ever seen looking at any public policy programs in the course of my career.”

A home visiting program is a voluntary program that connects parents with service providers, like nurses or social workers, who help address challenges. In August, the United States Department of Health and Human Services issued $106 million in grants to support the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program established by the Affordable Care Act. As of November, Michigan has been awarded $34.4 million in federal funding for this program.

The Michigan Council for Maternal and Child Health is working to help build a systematic approach to Michigan’s home visiting program, making sure a variety of models with quality professional resources are available to meet families’ needs.

“We’re very involved in trying to make sure that home visiting has the support it needs in Michigan,” says Amy Zaagman, executive director. “If we don’t build a system of home visiting in Michigan with a number of models available to families, we don’t think that we’ll ever see the full benefit. That will require additional investment.”

The report recommends a suite of policy options to improve access to home visiting, including providing grants, technical assistance, serving the neediest children first and assisting in community outreach programs.

Medical homes show promise for investment

Access to medical homes is another promising area for investment, according to the report. The American Academy of Pediatrics defines a medical home as a home base for a child’s medical care that provides better outcomes than sporadic, disjointed care in emergency departments, walk-in clinics and urgent care facilities.

Maureen Kirkwood, president and executive of Health Net of West Michigan, helped launch and oversee the Children’s Healthcare Access Program (CHAP) in Kent County.

“We knew the data showed a disparity between health outcomes for children on Medicaid versus kids with private insurance in Michigan,” says Kirkwood. “CHAP was formed in 2009 as a demonstration project in Kent County, under the theory that if we could work to provide access to high-quality primary care to children on Medicaid, we would decrease their hospitalization rates and their use of the emergency room, and see better health outcomes.”

The pilot succeeded in these goals, according to Kirkwood.

“We showed positive outcomes in cost reduction, quality of care, and health,” she says. “We were able, over the course of a two-year period, to show $1.53 in savings for every $1 invested.”

The CHAP program works as an intermediary, connecting families with medical homes in the area and with other services as needed. It functions as a shared resource for private medical practices in the area.

“We provide something that a lot of communities still do not have –a centralized, neutral resource that family practices can refer families to,” she says. “We function as a parent education and engagement arm of the private practices. We contact the family and give feedback to the practice to let them know what we did. It saves busy practices from having to dial a bunch of different phone numbers to find an agency that might be able to help.”

The report recommends providing matching grants to communities to develop CHAP programs, funding technical assistance and long-term evaluation.

High-quality child care and preschool for 3-year-olds are the final two areas recommended for investment. According to the report, the cost of child care is high and rising, and the benefits of early preschool and high-quality child care are well documented. It recommends increasing reimbursement rates for high-quality child care, evaluating Great Start to Quality, the system used by the state to rate child care, and raising awareness of Great Start Connect, the Michigan Department of Education’s web resource to access child care ratings. The report also recommends the state conducts a pilot to study the effectiveness of preschool for 3-year-olds, such as the studies at The Children’s Center.

Report serves as a good start

“This report is not an exhaustive list of what we need to do, but it includes the four strategies that have the most research to support investment,” says Susan Broman, director of Michigan’s Office of Great Start, which oversees early childhood efforts in the state government.

“There are other strategies and other things we would support, but these are the four that emerged as the strongest,” she says.

Broman points out transportation as another need that must be addressed to allow all four of these measures to be effective.

“We need to increase access to transportation, and that cuts across all of the services,” she says.

Erica Hill, education specialist with The Children’s Center, agrees.

“Our families struggle with transportation issues,” she says. “Especially when we had issues like the weather — they can’t stand out at the bus stops or get out of their driveways because the streets haven’t been plowed.”

Integrating these services is also important, according to Hill.

“That’s something that we do really well because we are part of a center with an array of services to support children,” she says. “We don’t have to go through a lot of red tape to get families the services that they need if children are experiencing trauma or have some cognitive issues.”

This piece was made possible through a partnership with Public Sector Consultants.

Photos by Amy Sacka at The Children’s Center.