Stabilizing Detroit’s neighborhoods, one house, one family at a time

For Detroiters who cannot qualify for a traditional mortgage, community development organizations use creative means to help individuals and families finance their first home.

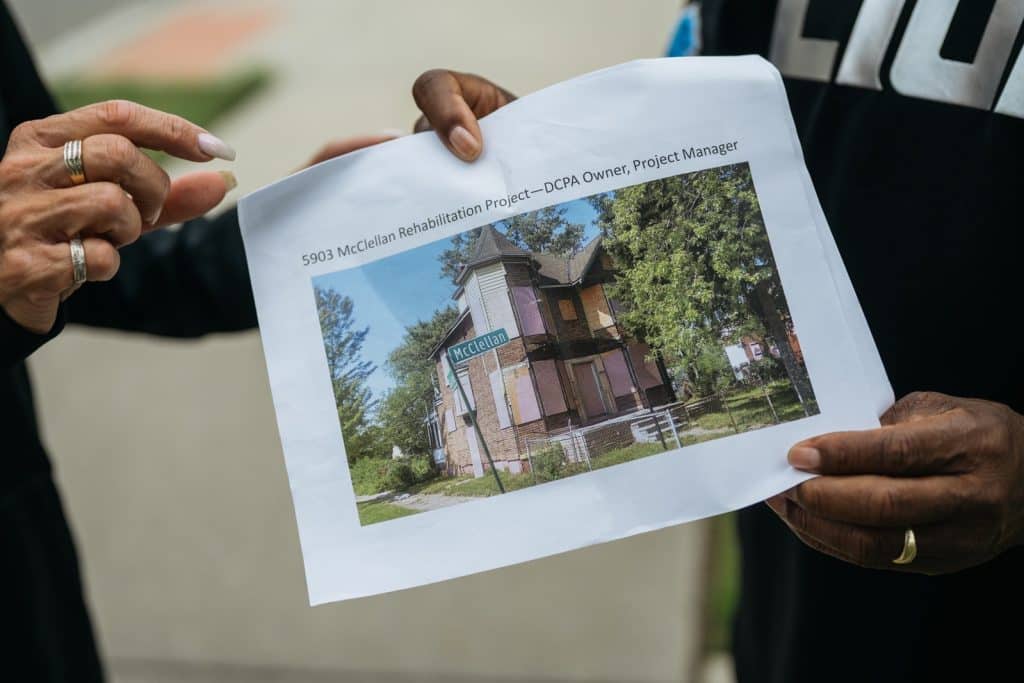

To see the beautiful house on McClellan Ave., impeccably kept with colorful flowerbeds in front and a charming gazebo in the back, you’d never imagine it was once just another abandoned Detroit house awaiting a wrecking ball.

Thanks to a dedicated nonprofit, Detroit Catholic Pastoral Alliance, and a hardworking couple, Lynne and Johnnie Williams, the house that could have been fated to be a cloud of dust and an empty lot is a thriving asset in a stable neighborhood – and its owners, once in the grip of substance abuse, are assets to their community as well.

Detroit Catholic Pastoral Alliance has been buying and renovating single-family homes and apartments in Detroit’s Gratiot Woods neighborhood for nearly 20 years. Founded in the wake of the 1967 uprising, the alliance has worked to engage community members in the social, moral, and political issues of the day and to actively work against racism.

Housing connects to that in many ways – a lack of access to homeownership, for example, means Black families have exponentially less generational wealth available to them than white families.

For DCPA, creating safe, affordable, well-maintained housing means stabilizing a neighborhood that serves as an important gateway to the city. DCPA renovated its first home, donated by a parish member in 2006, and has since built or renovated five multi-family projects in the neighborhood and several more single-family homes.

Redeeming homes, redeeming people

One of those homes went to the Williams family, owners of the caringly maintained home on McClellan. Their own story parallels that of their home.

“We’ve always said this was the house God had for us all along because, just like us, it was on the demolition list, and, just like us, it was completely restored,” says Lynne Williams. She and her husband Johnnie were both struggling with drug addiction, but were able to get clean and sober 15 years ago.

Once they were out of treatment and trying to create a new and positive life for themselves, they wanted to leave the neighborhood they had been in and move away from bad influences. One day, Williams was driving down Gratiot and saw one of the apartment projects DCPA had renovated. She called, and they landed the last apartment available in the building.

A few years later, they decided they wanted to move into homeownership. Because their experience renting from DCPA was so positive, they reached out to the organization to see what else was available. The house on McClellan was under renovation, and Williams admits she was very skeptical at first. “I didn’t know how they were going to renovate it!” she said.

After extensive work on the house, they moved in during 2017 and have been making it their own ever since. They now have three rescue dogs and two cats, have put extensive efforts into beautifying the home, and they even hosted a wedding for Lynne Williams’ best friend in early September. Williams is also a community representative on the board at DCPA.

(Photo: Steve Koss)

(Photo: Steve Koss)

Due to the Williams’ history, they would not have qualified for a traditional mortgage. DCPA worked with them on a land contract to allow them to buy their home. DCPA also frequently uses what is called a “soft second mortgage,” where the organization is in second position in financing the house and will reap some of its investment when it sells.

Stabilizing a neighborhood

Because the nonprofit’s goal is neighborhood stabilization, it also requires that homeowners not sell the home for a designated period of time. This avoids issues with someone flipping the home quickly instead of investing in the neighborhood, as intended.

“The way that we’re looking at it now is mostly as a way to be able to complete these projects without a subsidy and to bring up property values in the neighborhood and also to encourage home ownership,” says Cleophus Bradley, executive director of the Detroit Catholic Pastoral Alliance. “We don’t want them leaving and cashing out any type of equity they may have in the home. You want them to have a stake in the community for at least five years.”

(Photo: Steve Koss)

DCPA accomplishes its mission through a variety of financing methods, including taking advantage of available subsidies through the City of Detroit and the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. A bequest from a priest at the Church of the Nativity in the neighborhood means they can currently complete most projects without a subsidy. This is advantageous, as subsidies create more red tape and can slow down development.

Previous building projects also help fund the work, either through profits from homes sold or from rental income at one of the apartment projects DCPA has renovated.

”We’ve survived throughout the years because we haven’t relied on one particular source of income the whole time. And even as it relates to income from our real estate portfolio, we have a good mix of commercial and residential,“ says Christopher Bray, DCPA director of housing and finance.

“We’ve got something special going on in the neighborhood, in terms of the different types of housing available and the kind of investment that we put in, both in terms of actual bricks and mortar, repaving alleys and neighborhood beautification, and then also community organizing and things of that nature,” Bray says.

Meeting the need for affordable homes

DCPA is one of several organizations in the city attempting to address the affordable housing crisis in a city that’s rapidly changing and with an uncertain federal funding environment. Lisa Johanon, executive director and housing director of Central Detroit Christian Community Development Corporation, says it’s unclear what the future might hold for affordable housing.

“We don’t know what the final outcome of the federal government’s funding is, as it relates to CDBG [Community Development Block Grant Program] and HOME [HOME Investment Partnerships Program] funds,” she says, noting that at one point this year those funds were entirely gone from the federal government and then were restored.

“That’s going to have severe implications on affordable housing going forward,” she says, “I’m not being optimistic, that’s for sure.”

Another issue is the rapidly rising home prices in the North End, where Central Detroit CDC is located. Johanon says it’s not as simple as pointing fingers at gentrifiers coming in and making neighborhoods unaffordable.

A $200,000 house that would have sold for half that a few years ago may be out of the price range of a traditional resident of the neighborhood, but it also means the longtime resident whose home may have been worth considerably less several years ago is now able to see a return on the financial and emotional investment they have made in the neighborhood over decades.

Central Detroit Christian CDC is focused on children, and housing is an outgrowth of that mission to educate and care for children. That’s because once a family finds stable housing, all sorts of other potential issues are headed off.

A stable home means children are not moving schools constantly, the family’s stress is lessened, and the parents can plan a future because they know what their housing costs will be and that their investment will most likely appreciate in value, allowing them to build wealth.

To that end, Central Detroit Christian CDC offers training and counseling for potential homebuyers, ensuring they understand the costs of homeownership, how financing works, and how to avoid foreclosure or eviction. The organization also provides other services, such as child care and after-school programs for children, that ease families’ overall financial burden.

“If we put you in a house and you’re paying 50% of your income, which so many Detroiters are, something catches up so that you can’t pay this bill or that bill. And eventually it becomes your rent,” she says. “We want to have enough services for you, if that’s what you need. We’d rather work with folks that way.”

Resilient Neighborhoods is a reporting and engagement series examining how Detroit residents and community development organizations work together to strengthen local neighborhoods. It’s made possible with funding from The Kresge Foundation.