How generations of Detroit visual artists are feeling about the rise of AI

As AI use continues to grow, Detroit’s creative community is navigating what it means for the future of art, and the conversation has many layers.

Is it a tool? A threat? An abomination? Or something else entirely?

Artificial intelligence is changing the way the world makes, sees, and thinks about art. Detroit’s creative community is no exception.

Some artists lean on AI as a collaborator, others reject it altogether, and many fall somewhere in between, trying to figure out what it means for their creativity and their livelihoods.

In just one year, more than 15 billion images have been generated using text-to-image AI tools.

While there isn’t a clear generational divide, many local artists agree on one thing: Detroit’s art community is split on the topic — sometimes strongly.

And the future? Completely unknown.

For 63-year-old artist Chazz Miller, AI hasn’t replaced creativity — it’s reignited it.

“I always wanted to be a painter,” says Miller, who co-founded Detroit’s Artist Village and has painted murals across the city. “That’s what’s so ironic about AI. It actually makes me want to paint even more. It’s just a nice yin and yang type balance.”

Miller remembers being “anti-computer” when digital billboards started replacing hand-painted ones, but curiosity eventually won out. “I’ve just always had a desire to learn,” he says. “I’m an eternal student.”

When he first encountered Google’s DeepMind beta tester program years ago, he began experimenting and never stopped.

“It’s a tool,” he says. “And it’s about the individual and how you use it. A fork can feed you; a fork can stab you to death. It’s not the AI — it’s the guy with the AI that other artists got to worry about.”

For Miller, the artist’s intent matters most.

“The idea is the art,” he says. “All these people are going to have these tools, and they’re going to be cranking out so much AI slop that it’s going to be hard to sort through the noise. You’ve got to develop your own brand.”

That “AI slop,” as many are now calling it, is one of the things that worries Naomi Sharp, a 24-year-old Detroit artist who founded The Creative’s Oasis, a group supporting artists’ mental and creative well-being.

“I think it’s an abomination,” she says plainly. “The kind of sh*t people are making with AI is deplorable. The little good it has done and can do is exponentially outweighed by the harm it is doing and will continue to do.”

For her, the issue isn’t just aesthetic. It’s ethical and existential.

“I have not used that once, and I stand on that,” she says. “Who has your data now? Who are you actually talking to? This thing doesn’t have feelings. It was made by people. And those people don’t have your best interests at heart.”

She adds, “It’s so ironic that after all this time of us telling older folks to understand the internet, they decide to accept the worst thing that has come out of it. You’re over here trying to generate sh*t and think that’s reality. I’m scared.”

Yet, her fear hasn’t led to despair, but rather strengthened her commitment to originality.

“I think this has given me the opportunity to really appreciate how creative I am and how powerful imagination is,” she says. “This is the deepest opposite of originality ever. It just combs what already exists to make something without any sort of intention.”

Somewhere in between is another Gen Z artist, 25-year-old illustrator and designer Dehvin Banks, co-founder of The Vision Detroit.

“Everything is looking the same, everything is feeling the same,” he says. “So, as far as my creative work, specifically, I try to use it as little as possible. In the ways that I do use it, however, are like ideas. If I have an idea that isn’t the most fleshed out, oftentimes, I will drop it into ChatGPT, or, even more recently, Gemini, to see if it will flesh it out, see what type of paths it could give me. And then once it gives me those, I’ll use my own creative brain to figure out what that would look like.”

When it comes to what he’s heard from other local artists, Banks says, “There’s definitely a split. Some people are embracing AI fully, others are completely against it. And then there’s a fair amount in the middle, which is where I am.”

He calls AI “a tool that you pull when you need it, and if you don’t need it, leave it in the toolbox.”

“I think it’s only a threat if you’re unwilling to learn the processes and learn what the hell it can do,” he says. “I think when you’re oblivious to those facts, you get left behind. Not saying that you necessarily need to use it in your work, but you need to be aware of where your pitfalls are and where AI may be able to pick up.”

Banks has also seen how AI affects perception in the art world.

“People have been getting called out because others think their art is AI, even when they have time-lapses showing they actually made it,” he says. “There’s been a huge decline in people buying digital because it’s hard to tell whether someone did it by hand. But there’s also been a resurgence of people seeking out more human experiences — handmade drawings, handmade crafts, handmade clothing. They want real experiences.”

A recent Artsmart study found that 29% of digital artists currently use AI in their work.

To push back against growing skepticism around digital art, Banks has been returning to traditional methods, a shift he says has brought him closer to his craft than ever.

“Using real inks, real paper, real pencils,” he says. “You don’t have an undo button. You can’t move things around; you just have to redraw it. It’s been a learning curve, but it’s gotten me closer to my art than I’ve been in years.”

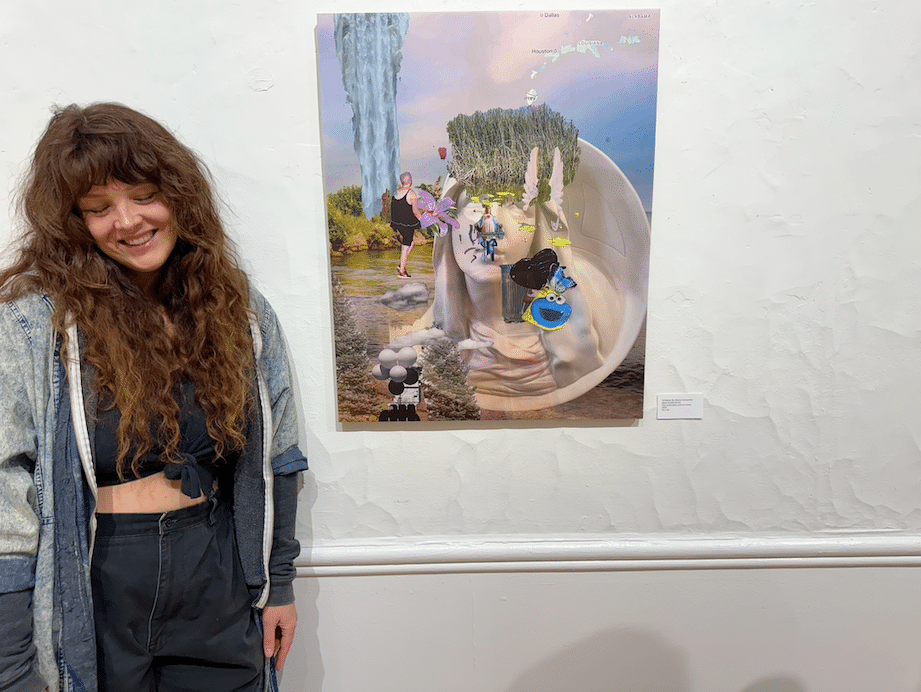

Many artists, not only Banks, find themselves somewhere in the middle on the topic, like millennial street photographer and collage artist Amelia Burns.

While her main concern is the environmental cost of AI, she believes “there’s no way to not use AI.”

“People are like, ‘Well, it’s ruining everything,’ and I think there’s no stopping technology to a certain extent,” she says. “You can use any technology and make it your own and use it to make your work, so I don’t tend to be upset about technology generally moving on. I think it’s just the natural way of things, and you can integrate it into your practice or not.”

She’s open to using AI for logistical tasks or built-in Photoshop tools, but the environmental impact still gives her pause.

For example, generative AI models have been shown to significantly increase electricity and water demand — one MIT analysis warns of surging data center emissions triggered by AI workloads. In some estimates, a single AI request can require ten times more electricity than a typical Google search.

Overall, she believes it risks dulling creativity as time moves forward.

“I think there’s a risk of people not taking the time to think about their ideas, so it diminishes the need for critical thinking,” Burns says. “If people are taught to think critically about media from the beginning, it’ll be easier to differentiate that and have people still be critically thinking.”

At The Well, a community gathering hosted by Sharp’s organization, conversations about AI come up often. “We’ve had conversations about what it’s doing, what it could do, and how we feel about it,” she says. “It’s not the focus, but people are figuring out what it is — or trying to.”

Miller believes curiosity, not fear, should guide the conversation.

“If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at will change,” he says, quoting Michigan philosopher Wayne Dyer. “I want to teach other artists how to think out of the box.”

Banks emphasizes balance: “Learn the fundamentals. Know how to do it well. But also, look at the benefits of AI and know how to use it responsibly.”

Sharp, meanwhile, insists the future depends on discernment. “If you use AI, just investigate,” she says. “Ask yourself, is the convenience worth the sacrifice?”