Which Detroit neighborhoods are most vulnerable to major change? New reports uses data to find out

Data Driven Detroit just released Turning the Corner, originally an attempt to develop a predictive model for resident displacement. The final result, however, is possibly more interesting and useful.

As Noah Urban puts it, determining a predictive model for resident displacement is the “holy grail” of urban planning research. Figure that out, and cities would be able to anticipate and mitigate the effects of transformational change brought on by the forces of gentrification, well before it happens.

Yet try as they might, researchers and academics the world over have yet to develop an effective predictive model for such a thing. Of course, that hasn’t stopped them from trying.

Urban is senior analyst and project lead at Data Driven Detroit, the Detroit-based data collection and analysis firm headquartered in TechTown Detroit. He and his team are celebrating the release of Turning the Corner, their own attempt at developing the predictive model for resident displacement.

As in many scientific pursuits, D3’s report turned out to be something different than initially intended. While not the predictive model researchers hoped for, Turning the Corner is instead an explanatory model, one that is still very much useful in getting ahead of the type of transformational change that leads to resident displacement.

A more complete picture

D3 took a four-prong approach to gather its data, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative research techniques, as well as citizen advisory groups and the cross-site sharing of information.

“We had explored displacement from the other side when working on the Blight Removal Task Force, exploring the downward spiral of disinvestment,” Urban says. “Now we wanted to look at how investment affects displacement.”

In building their model, D3 wanted a system that reflected the state of the city in real time, or as close to it as possible. Rather than rely on federal data bogged down by a five-year lag, D3 used data from sources more regularly updated, like the city of Detroit’s Open Data Portal.

In addition to the more traditional hard-number sets of quantitative data, D3 also built their Turning the Corner map and analytical report using qualitative data. D3 convened community advisory groups and held one-on-one conversations with actual residents and business owners to create a more complete picture of Detroit neighborhoods.

“Community change is best understood by those who it’s directly happening to,” says Keegan Mahoney, an advisor to the project on behalf of the Hudson-Webber Foundation, one of its local partners. The Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and The Skillman Foundation also provided local support.

“This data is most important to the people watching it happen outside of their windows.”

Two areas of the city, the North End and southwest Detroit, were singled out as places already undergoing a transformation as a result of the influx of new residents. Amanda Holiday, executive director of the Chadsey-Condon Community Organization, which represents the Chadsey-Condon neighborhood in southwest, believes the information will allow community groups to be proactive in the face of transformational change.

“I think this has been very important because we’re one of those neighborhoods that is on the cusp of changing,” Holiday says of her neighborhood, which straddles Michigan Avenue, from I-96 to Wyoming Avenue. “It’s been very informative to see the data because we can say, ‘Look, it’s happening here.’ That way we can be more on top of it in a way that other neighborhoods haven’t been able to.”

With the help of the Community Development Advocates of Detroit, Chadsey-Condon has already held community meetings to develop a neighborhood plan to guide future development.

The pros and cons of growth

Community change can be a tricky line to walk. As more people move into a neighborhood, long-time residents can be affected in both negative and positive ways. Some residents may be forced to move as a result of higher rents and property taxes, while others may want to start making extra income on their properties.

D3 hopes that people use Turning the Corner as a guide in their decision-making.

“I think it can help inform people who want to invest in a thoughtful manner,” says Urban. “You can’t guide market forces; a lot of things go into that. But this is great information for people wanting to be conscientious about development.”

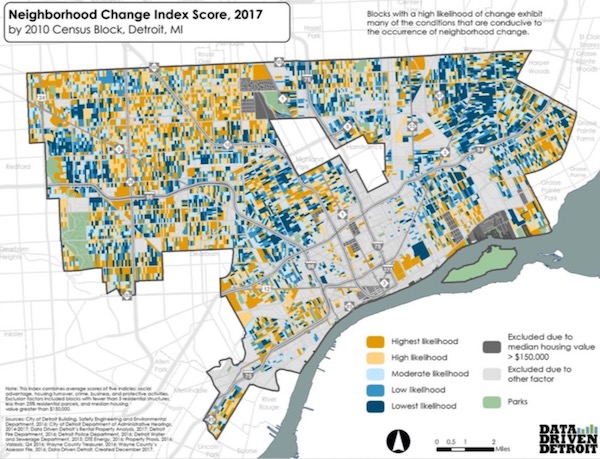

The map identifies which city blocks are more susceptible to transformational change and resident displacement. Foundations, block clubs, CDCs, residents, and other stakeholders can then take that information and introduce new measures to stanch displacement in the targeted areas, be they short-term interventions, long-term investments, or both.

An example of short-term intervention, says Mahoney, is the Stay Midtown initiative from Midtown Detroit, Inc. The Midtown district, removed from the Turning the Corner study because it was determined that transformational change has already taken root, launched the Stay Midtown residential assistance program to help current residents meet the rising costs of rent in the popular and increasingly expensive neighborhood.

Long-term investments, like adding more low income and affordable housing options, can help eliminate the need for short-term interventions in city neighborhoods deemed more vulnerable to transformational change. The idea is that Turning the Corner will provide early signals of resident-displacing transformational change, before it’s too late.

“With the investments occurring in different neighborhoods, you want to make sure that current residents are there long enough to benefit from the quality-of-life improvements happening,” says Mahoney. “Detroit is actually lucky to be ten to fifteen years behind the country in some ways because we can take lessons learned elsewhere and apply them here.”

While Detroit may be behind in some facets, be they economic or otherwise, the city is ahead in many other ways. The Turning the Corner project could become a guide for many American cities. It’s become part of a larger multi-city initiative from the Urban Institute’s National Neighborhood Indicator Partnership, the Funders’ Network’s Federal Reserve-Philanthropy Initiative, and the Kresge Foundation. Phoenix, Buffalo, Milwaukee, and Minneapolis/St. Paul are also conducting their own versions of Turning the Corner.

Researchers are curious to see if what’s true about transformational neighborhood change and resident displacement in Detroit is true in other American cities with similar demographics and markets. And while this Detroit’s iteration has been completed, the map and its data will be continually updated, providing as up-to-the-date information as possible.

“The goal is to understand neighborhood change. The earlier you get a handle on it, the better,” Mahoney says. “This is the beginning of a process, not the whole process.”