SimmerD: Serving up love (and PB&Js) at Corktown soup kitchen

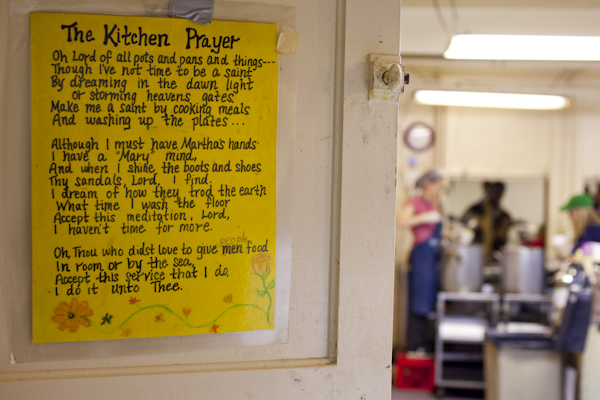

Our food writer gets over a fine dining hangover by volunteering for service on the food line at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which has been helping feed the needy since 1976. Noelle Lothamer reports from the inside.

The orders ring out:

“Two potato, three mac ‘n’ cheese.”

“Four potato noodle.”

“One of each.”

In

a basement kitchen on Trumbull and Michigan, I dole out scoops of

noodle soup and macaroni and cheese with a pert blond eighth-grade

volunteer named Kristy. This is a far cry from the well-loved and lauded

mac ‘n’ cheese served just up the street — it’s made with

industrial-sized cans of processed cheese sauce, in which I suspect

there may not be any actual dairy. But this is what’s being offered, and

no one is complaining. Many come back for seconds and thirds; most take

extra, in Styrofoam containers, either to put in the fridge at home or

to take to friends or family. In addition to the soup and macaroni,

there are peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, American cheese

sandwiches, doughnuts, muffins and bagels.

Visiting so many

swanky restaurants for Detroit Restaurant Week last month, while a fun trip,

left me with a fine-dining hangover of sorts, and got me thinking about

what a tiny percentage of Detroiters would ever be able to actually have

a meal at any of the places we visited. By coincidence, a couple of

weeks later I was introduced by a mutual friend to Jeff DeBruyn. For the

last five years, DeBruyn has worked with Manna Meal, a soup kitchen run

out of the basement of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, where he acts as a

“peace-keeper” in case of any incidents. I asked him if they could ever

use a hand, and he replied that I was welcome to come by any time and

they would find something for me to do.

And so I find myself at 7

a.m. on a warm Friday slathering stiff peanut butter onto uncooperative

slices of too-soft Wonder bread while chatting with a retiree named

Marge. Somewhat surprisingly, she is quite “food-aware,” asking me

whether I use refined salt and whether I know about A1 and A2 milk (I

did not, so I Google it when I get home). It feels more than ironic to

be discussing the unhealthiness of the Western diet and then proceeding

to serve a meal in which there were no fresh fruits or green vegetables

and the only protein was in the peanut butter sandwiches, but there we

are. It’s a catch-22 because Marge intimates that in her experience,

even if we were to serve a vegetable, most diners would pass it over in

favor of the carbs.

I ask one of the other volunteers where the

food comes from. She tells me that Marianne Arbogast, who co-manages the

kitchen with Father Tom Lumpkin, gets the food from various sources

such as Costco and day-old bread stores, shopping around to stretch

their dollars. The bottom line, quite obviously, is that the cheaper the

food, the more people they can feed. I ask if they ever run out of food

and am told that if they run out of the “main dishes,” they just make

more sandwiches.

Sometimes there are food donations. The day I am there,

a man shows up with several boxes of Dearborn brand

hot dogs left over from a UAW picnic. These are cut up to be added to

the next day’s bean soup. One of the men in line, seeing the meat,

cajoles us to give him a cup on the sly, but is refused. “If I give some

to you, everyone will want them,” the volunteer says apologetically.

After

prepping the PB&Js, we get ready to open for business and I take my

place in the serving line. The people who come through, the majority of

whom are men, are mostly friendly and in good spirits. One sings

commercial jingles to us; another gives us a few bars of harmonica. One

man remarks cheerfully that “every day I wake up alive is a good day.”

Everyone seems to be courteous to each other and there is no unruliness.

It’s a slow day for DeBruyn, who sips coffee and reads the paper,

glancing up occasionally to survey the room.

My station is right next

to a telephone mounted to the wall, and during the course of service,

several people come to use the phone. I overhear the conversation of one

man who is having trouble with his Social Security checks and has been

kicked out of a group home because they couldn’t get his checks cashed.

For many of the people it serves, the soup kitchen is more than a place

to get a free meal: it’s a “home base” where they can receive mail, make

calls, and get assistance with finding medical care.

As the

neighborhood develops and changes, Manna Meal’s presence has been the

object of some controversy with business owners and residents, some of

whom would prefer to drive out (or at least discourage) the indigent

element. But many the people it serves have been in Corktown since well

before its revitalization, and the soup kitchen, open since 1976, isn’t

going anywhere.

Although I used to live just up the street, I had

been unaware of Manna Meal prior to meeting DeBruyn. An online search

turns it up on a listing of soup kitchens on the Archdiocese of

Detroit’s website, but that’s about it. Curious as to how they are

funded since they seem to have little or no publicity, I ask Marianne.

Unlike the widely-known Capuchin Soup Kitchen on the East Side, which

has a well-developed website where people can donate online, Manna Meal

is funded entirely on personal donations and a once-a-year charity golf

outing. Many of the volunteers have worked there for 20 or more. In an

age where everyone is pushing their cause via a Facebook page, I marvel

at the fact that this organization moves along quite nicely on good

old-fashioned word-of-mouth community involvement.

Still, there

are needs that are not always filled. As I serve up cups of soup, a man

asks whether there is any “hygiene.” I don’t understand what he is

referring to so I ask another volunteer, who explains that there are

sometimes items on hand like toothpaste, soap, deodorant, and razors in a

drawer for people to help themselves to. Today there are no toiletries

to be had. The man thanks me for checking and wanders off with his soup.

For

anyone interested in assisting Manna Meal in their mission, donations

can be sent in care of Manna Meal at Most Holy Trinity, 1050 Porter St,

Detroit, 48226. In-person donations can be made at the soup kitchen

during the hours they are open (Monday-Wednesday, Friday-Saturday, 7-11

a.m.). Currently, they are most in need of toiletries, socks, and men’s

t-shirts; they do not, however, accept bags of clothing. Anyone

interested in sponsorship or participation in their annual golf outing

(held this year on Sept. 10) can contact Paula Belanger at 248-561-0468.

Food writer Noelle Lothamer pens a food blog that goes by the tasty name Simmer Down! Look for her monthly Model D contributions in SimmerD.

All photographs © Marvin Shaouni Photography

Contact Marvin here.