RecoveryPark rehabilitates a neighborhood and the lives of returning citizens through farming

A commercial-scale agriculture nonprofit, RecoveryPark also employs Detroiters who have prison records, literacy issues, substance abuse recovery issues, and other past struggles that make it difficult to find work.

Having spent 24 years in prison, Clinton Borders was more than ready to make a fresh start when he was released in 2011. But most prospective employers had no interest in giving him the second chance he needed.

“When I came home, I was in my fifties,” Borders says. “With that box on the application for ‘felon,’ I found it very difficult to get employment. You can get employment, but it’s not meaningful. And not anything where you could make a livable wage.”

But last year Borders found a solution for his employment woes at a fledgling urban farm called RecoveryPark Farms. It’s the first major project of RecoveryPark, a nonprofit that aims to employ Detroiters who have prison records, literacy issues, substance abuse recovery issues, and other past struggles that make it difficult to find work. Full-time jobs at RecoveryPark Farms start at $11 per hour and offer full health benefits. In addition to seven core staff, the nonprofit has so far hired two staffers with prison records; it will add four more soon.

RecoveryPark CEO and founder Gary Wozniak’s passion for this project is deeply personal. Wozniak is a former stockbroker who served three and a half years in federal prison in the late ’80s after using clients’ money to support his own drug addiction.

Wozniak is now sober and has decades of entrepreneurial experience under his belt. In the early ’90s he became one of Jet’s Pizza’s first franchisees. But he hasn’t forgotten the struggle of reestablishing his life when he got out of prison.

“We tell people you’re going to prison, you’re going to do your time, you’re going to come out, and you’re going to become a productive member of society again,” he says. “But that’s not what society does. It’s almost like Hester Prynne in ‘The Scarlet Letter.’ You’re always going to be branded.”

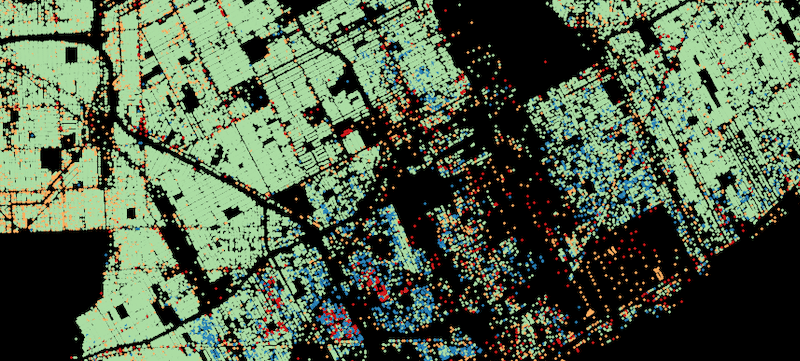

While volunteering with Detroit rehab organization Self-Help Addiction Rehabilitation in 2008, Wozniak hatched a unique concept to attack that problem while also addressing two other major needs in the Detroit community. He envisioned a commercial-scale agriculture project that would repurpose a blighted neighborhood as a farm, reinvigorating its surroundings while also serving Detroit restaurants’ growing, often unfilled demand for Detroit-grown produce. The result is RecoveryPark Farms, a nearly 50-acre plot on the city’s lower East side, just south of Hamtramck and east of Midtown.

“Tomatoes don’t care if you can’t read or write,” Wozniak says. “They don’t care if you’re coming out of prison. They’re basic skill sets you can teach anybody, and you get immediate feedback from growing.”

Rethinking a neighborhood

The RecoveryPark Farms project began in earnest in late 2015, when RecoveryPark finalized an agreement to lease nearly 40 acres of city of Detroit-owned property for five years at $105 per acre per year. Since then, RecoveryPark’s small staff has worked quickly to meet a variety of requirements imposed by its agreement with the city. They must maintain a staff that’s at least 51 percent Detroit residents, demolish all blighted structures in its new footprint within one year of taking possession, and operate at least three acres of greenhouses or hoop houses within two years.

Wozniak and his team have had to work harder than expected to stay on track to meet those deadlines, partly due to the massive hidden amounts of rubble left behind from many ’70s and ’80s demolitions in which homes were bulldozed into their own basements.

“There’s a lot of buried stuff here,” Wozniak says.

But if you drive RecoveryPark’s main artery along Chene Street, numerous signs of rejuvenation are now visible. RecoveryPark has repainted and renovated the long-defunct Chene-Ferry Market, where it will cosponsor a concert series this summer with the Chamber Music Society of Detroit and the Raven Lounge. Makeshift bus shelters dot the sidewalks along the property, built and designed by RecoveryPark and Challenge Detroit fellows. A group of raised beds across the street from RecoveryPark’s office on Chene form a community garden, from which neighbors are welcome to pick free produce. A block west of Chene, there are freshly dug swales and catchment ponds, part of a stormwater reuse project sponsored by the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

But of course this is a commercial-scale farm, and signs of its predominant function are visible as well. RecoveryPark recently erected its first three acres of high tunnels—steel-framed, plastic-covered, self-heating greenhouses also known as hoop houses. The nonprofit is required to complete three more acres of hoop houses by its three-year mark, and another three by the four-year mark. And construction will begin this spring on what will eventually be almost 40 acres of heated glass greenhouses.

RecoveryPark hydroponic greenhouse grower Jeff Gilbert says the farm will focus on specialty produce.

“Chefs want something unique,” he says. “They want something fun. We’re not growing huge tomatoes that taste like nothing. We’re going to be focusing on taste and quality. We’re going to stretch ourselves to have some unique products, but that’s a fun challenge to have.”

The power of collaboration

RecoveryPark went through a lengthy development period in the seven years between Wozniak’s original concept and the acquisition of the RecoveryPark Farms plot. Wozniak says countless partnerships with other nonprofits, community organizations, and government bodies were instrumental throughout that process.

“If I had to replicate the services I’ve gotten through these partnerships, I couldn’t find enough money to do that,” he says. “A lot of the partnerships are just kind of ad hoc meetings, pro bono arrangements, where we’re just cross-sharing ideas … We just wouldn’t have the financial capacity to hire all the contractors and subcontractors to get that work done.”

Wozniak rattles off a list of organizations who have assisted RecoveryPark: Wayne State University, the Detroit Collaborative Design Center, Gleaners Community Food Bank, TechTown Detroit, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, and more. On the capital side, the Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation was a major supporter, awarding the project a $1 million grant over four years starting in 2012. And, of course, RecoveryPark worked at length with the city of Detroit to assemble the 851 parcels of land that comprise RecoveryPark’s footprint.

RecoveryPark has also worked hard to build relationships with its neighbors, holding numerous community meetings and going door-to-door in the neighborhood to make local residents aware of the project and engage them in it.

“We want to be part of this community,” says RecoveryPark soil-based grower Michelle Lutz. “We are not here to run a business and not be good community neighbors and partners. I do not want people to feel ostracized from what we’re doing.”

The road ahead

RecoveryPark is preparing to scale up distribution quickly in 2017 as production increases with the new hoop houses and greenhouses. The nonprofit recently signed a contract to sell 100 percent of its produce to Del Bene Produce, which distributes to 440 restaurants within a 200-mile radius of downtown Detroit. Wozniak says the Detroit food industry is ready for a local supplier for “things that you’d want to see on your plate if you go to a high-end restaurant.”

“They’ll get them from wherever in the world they’re grown and charge appropriately,” Wozniak says. “So our value proposition is local growing of the same specialty produce, stabilizing the price so the restaurants aren’t subject to the highs and lows of where it’s coming from.”

Perhaps no one is looking forward to the coming scale-up as much as the formerly-incarcerated Borders, who has done much of his work so far in a single, training-oriented high tunnel operated by RecoveryPark near the Russell Industrial Center. He’ll be responsible for multiple hoop houses on the main RecoveryPark site when they get up and running this year.

“It’s so much fun,” Borders says. “You enjoy getting up in the morning and going to work. I’ve never had a job where I was excited to come to work.”

This article was underwritten by business accelerator and incubator TechTown Detroit.

All photos by Nick Hagen.