Rabbi Ariana Silverman finds new ways to connect the Jewish community in Detroit amid the pandemic

Faced with the unprecedented challenge of closing the Downtown Synagogue amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Rabbi Ariana Silverman discovered new ways to keep her congregation connected while following thousands of years of Jewish tradition.

A lot has happened in the decade since Rabbi Ariana Silverman moved to Woodbridge. After relocating from New York in 2010 with her husband, Wayne State University law professor Justin Long, Silverman says she was the only rabbi living in Detroit at the time and quickly became involved with the Isaac Agree Downtown Synagogue — the city’s last freestanding synagogue.

In 2016, following a half-decade of growth for the synagogue, Silverman was appointed its first rabbi in over 16 years. Since then, the synagogue’s membership has expanded to include over 360 households, representing more than 500 members. During a normal week of programming, Silverman says the synagogue keeps a lively schedule with worship services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings, holiday services, programs, classes, and “all of the good stuff you would expect.”

In early March, though, as news began circulating about the spread of COVID-19 in Detroit, Silverman says everything changed. Faced with the unprecedented challenge of having to close the Downtown Synagogue, Silverman suddenly found herself struggling to align thousands of years of Jewish tradition with modern ways of keeping her congregation connected.

Anticipating a looming crisis, the Michigan Board of Rabbis, which meets quarterly, scheduled a meeting to discuss the potential implications of the pandemic. “It was March 12, before [Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s shelter-in-place] order came in,” Silverman recalls. During the conference call, the rabbis consulted with a physician and discussed the virus. “Remarkably, we all decided to shut down our synagogues on the same day,” she says. By the end of that day, Silverman says “all of the progressive synagogues in Metro Detroit were closed.”

Although the decision was abrupt, Silverman says she doesn’t think the members of her congregation were particularly surprised. “I think people were expecting that there would be a change,” she says, adding that the decision to move services online was far more complicated than the choice to close the synagogue.

“The question of whether we would meet online is a little bit of a complicated one,” Silverman says. She explains that Jewish law forbids the use of technology on Shabbat, which falls just before sunset on Friday and lasts through Saturday night. Silverman explains there is also a requirement that in order to have a worship service, a quorum of 10 adult members of the Jewish religion be present to say some of the prayers — including memorial prayers for communal mourning.

“For most of history, you’ve counted those 10 people by having them stand in the same place. But that couldn’t happen,” Silverman says. “So it wasn’t just the format. All of the thousands of years of Jewish law had to be thought about and interpreted, because the decision to meet online also was a decision to count people online toward that quorum of 10 people.”

Silverman says the choice to move services online was further complicated by the synagogue’s lack of affiliation with any specific Jewish movement. (In the Jewish faith, the three major movements, or streams, include Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism, and Reform Judaism, which is also often referred to as Progressive Judaism.)

“For some [Jewish] communities, the answer was simple — they simply couldn’t do it because there’s no way they would use technology on Shabbat,” she says. “We sort of fell in the middle. The Downtown Synagogue is not affiliated with one of the Jewish movements. […] We’re one of the few synagogues that doesn’t subscribe to a specific movement.”

In the absence of a denominational affiliation, Silverman says the Downtown Synagogue had to make its own decisions about the use of technology on Shabbat. “A lot of the decision [to move online] was mine,” Silverman says. “I felt it was important for our community to continue to be able to see each other, and to continue to be able to feel a sense of the sacred on Shabbat.”

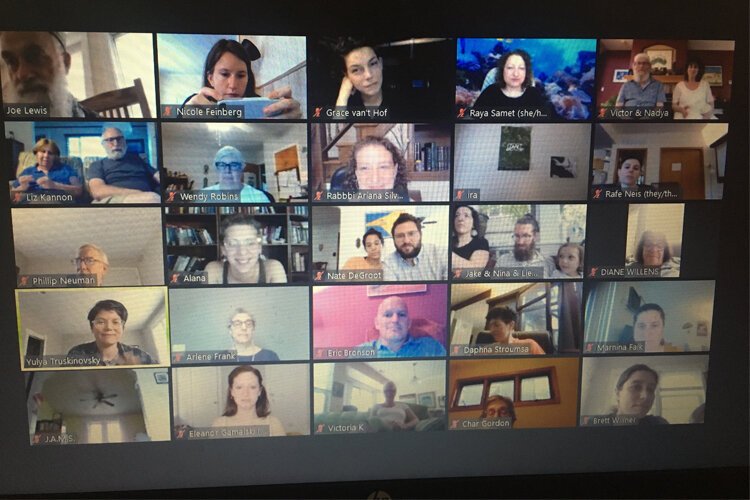

With only 24 hours before the next worship service, Silverman worked quickly to choose an online platform and organize her congregation around it. She says she chose Zoom because she “wanted people to be able to see each other.” Still, Silverman admits the platform has had its own set of benefits and disadvantages, particularly when it comes to group singing. “It’s this incredible cacophony because of the sound delays,” she says, laughing. “I always tell my congregants that I think it’s a beautiful sound — the sound of people trying to sing together.”

The synagogue’s online worship schedule includes Friday services at 5:30 p.m. and Saturday morning services at 9 a.m. Silverman says each service includes additional time for socializing, and study time is built into the schedule for Saturday mornings.

“The pivot continues even beyond our regular Shabbat worship services into things like how we do our programs and how we do our holiday celebrations,” Silverman says, adding that this year’s celebration of Shavuot, from May 28-30, presented a particular challenge.

“One of the traditions of the holiday is to stay up all night studying,” she says. “[Shavuot] celebrates getting the Torah — getting revelation at Mount Sinai.” During a normal year, Silverman says about 75 people would usually meet at her Woodbridge home around 6 p.m. to study, then scatter to homes around the Woodbridge neighborhood where they would attend classes and study Torah together until 2 or 3 in the morning.

Instead, this year Shavuot was celebrated on Zoom, utilizing breakout rooms for some of the classes. Silverman says the turnout was their biggest yet, drawing around 90 participants including some from around the country and even Ontario.

In addition to worship services and holidays, the synagogue has also added online services geared toward families and children. “[Children at the synagogue] suddenly couldn’t see their friends anymore, so it was a joy to see that it was actually helpful for them to be able to see each other, even if virtually, a few times a month,” Silverman says.

The question of how children have been impacted by the pandemic is one that hits close to home for Silverman. As a mother of two — Rebecca, 5, and August, 2 — she’s been forced to balance her responsibilities as a rabbi with those of a parent suddenly tasked with homeschooling her children. “One day [Rebecca] walked out of [school] and then she didn’t go back,” Silverman recalls. “That transition was incredibly abrupt. She’s been remarkably resilient, but it’s very hard.”

Still, Silverman is in no rush for things to return to normal. For the immediate future, she plans to continue services through Zoom until they feel it’s safe to hold them in-person again. Although she says the Downtown Synagogue is tentatively considering outdoor worship services toward the end of summer, there are no plans to reopen the building any time soon.

“I feel very strongly that it’s our obligation to protect the health and safety of our members,” Silverman says. “There’s a Jewish value called pikuach nefesh. It means ‘saving a life.’ The idea is that all the laws that come with Shabbat get nullified if it’s a question of saving a life. […] And as long as it seems that is what we’re dealing with, that’s where we’re going to put our emphasis.”

This story is part of an ongoing series done in partnership with Woodbridge Neighborhood Development to highlight stories of resilience in the neighborhood.