After the closing of GM’s Detroit plant, what lessons can be learned?

In the 1980s, the city of Detroit used eminent domain to clear a large swath of the Poletown neighborhood for GM to build a new assembly plant. Late last year, it closed. The saga requires us to to ask how Detroiters can make sure big development deals of the future are fair.

To watch the 1983 documentary “Poletown Lives” is to travel to another Detroit. One that’s bigger, but quickly getting smaller, and acutely aware of what’s slipping way. The film memorializes Poletown residents’ desperate, losing battle against Detroit and General Motors to prevent the forced sale and razing of their homes — and even their church — for a new factory.

That factory, officially known as GM Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly, faces closure next year, which raises the question of whether the city’s residents got what they paid for. And, more importantly, how Detroiters can make sure future big development deals are fair.

“All of us need to realize, this is still happening,” Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib told a crowd at the Wayne State Law School auditorium after a December screening of “Poletown Lives.” “You see it now even with the hockey stadium.”

Detroit has changed a great deal since Mayor Coleman Young, in a last-ditch attempt to retain auto manufacturing jobs, used eminent domain to clear land for a new GM manufacturing facility. For one thing, the local economy is less dependent on automaker jobs (Detroit-Hamtramck is now one of only two active car assembly lines in the city).

But with big developments breaking ground — be it Bedrock skyscrapers downtown, Ford’s fledgling campus in Corktown, or a new Henry Ford Cancer Institute in New Center — it’s worth evaluating what we can learn from Poletown.

Eminent domain

One of the most direct — and profound — changes in the wake of the factory’s construction has been in what’s considered appropriate use of eminent domain.

The city had been able to force the sale of homes to build the factory under the belief that creating and preserving jobs in Detroit constituted “public use.” That is to say a factory, like a highway or park, serves the greater community and thus overrides the concerns of a few individuals. The Michigan Supreme Court agreed to this argument in 1981, ruling in favor of the city and against the Poletown Neighborhood Council.

However, the public debate continued and largely turned against GM and the city. “The Poletown fallout occurred and grew until the Hathcock case,” says John Mogk, a Wayne State law professor who specializes in urban development.

In the 2004 Hathcock case, the Michigan Supreme Court considered whether Wayne County could use eminent domain to create space for a business park near Detroit Metro Airport. It was, the court conceded, similar to Poletown. Only now it argued the Poletown decision represented an “invalid reading of our Constitution.”

“In the twenty-three years since our decision in Poletown,” the majority stated in its ruling against Wayne County, “it is a certainty that state and local government actors have acted in reliance on its broad, but erroneous, interpretation.”

A subsequent 2006 referendum to amend the state constitution made Michigan’s eminent domain law even more restrictive. No longer can it be used to transfer private property to another private entity if the public “use” is jobs.

The changes were widely hailed as a victory for citizens over government and corporate overreach — the referendum passed with more than 80 percent of the vote. But not everyone’s sure it had the desired effect.

“I think it’s kind of unfortunate how Poletown set this precedent for overreach, and the reaction to that has ostensibly taken a lot of the teeth out of eminent domain,” says Francis Grunow, former executive director of Preservation Detroit and now chair of the Neighborhood Advisory Committee in the Little Caesars Arena district. “A stronger version of eminent domain might have been used effectively, creatively, in subsequent decades.”

One of the unintended consequences has been to hamper the city’s ability to pool land and attract re-development to areas outside downtown.

“You have to ask yourself, does the city need land assembly to be rebuilt outside of downtown? And I answer ‘yes,'” argues Mogk, who authored a legal opinion critical of the Hathcock ruling. “If you’re negotiating lot by lot, you undoubtedly are going to run into a lot of holdouts … Show me someone in the neighborhoods who has that kind of deep pockets and patience if we’re expecting that kind of development to happen anywhere else.”

And when businesses have proven willing to play the long game and negotiate, it hasn’t necessarily worked out for the benefit individual property owners. The Illitches, for instance, spent more than a decade quietly acquiring (and demolishing) homes and businesses on Lower Cass Avenue for its arena district.

Community benefits agreements

Regardless of what carrots are available to the city, most agree it should have a bigger stick.

“It’s not so much about granting the tax break, or incentives, or whatever it is,” Grunow says. “It’s the ability to have some amount of common understanding that if the developer doesn’t do what it says, what are the repercussions?”

Were the Detroit-Hamtramck factory built today, GM would be subject to the Community Benefits Ordinance, approved by Detroit voters in 2016, which requires large developers to report to a Neighborhood Advisory Council, like the one Grunow chairs, “to identify community benefits and address potential negative impacts of certain development projects.”

The councils, however, have limited ability to slow development — or take back tax subsidies — if its demands are not met. “There needs to be teeth and some sort of accountability,” Tlaib says.

She, like Grunow, cites community benefits agreements — binding contracts in which a community neighborhood association has legal standing — as a possible solution. “Mayors come and go. Elected city council members come and go. And they forget what these promises were.”

Successful community benefit agreements in other cities include the Oakland Army Base in Oakland, California which Model D wrote about in 2018. “The 2012 agreement with the city contained a living wage policy; requirements that 25 percent of jobs be reserved for the disadvantaged, low-income, and long-term unemployed; 50 percent of jobs be filled by Oakland residents; the creation of the West Oakland Job Resource Center that connects workers and employers to ensure community members get hired; banning of pre-screening for prior felonies; and a Mayoral-appointed oversight commission on which Revive Oakland has two seats.”

Others include the Los Angeles Staples Center and the new Pittsburgh Penguins arena. For an international example, Volkswagen’s plant in Dresden (see sidebar) showcases what can happen when a strong union and municipality work with a developer to secure a long-term commitment.

Mogk agrees contracts might work in certain cases, but cautions that they require a motivated developer — not one merely lured in by incentives.

“GM was really not interested in doing the Poletown plant. They would have preferred, as I understand it, to have built in some kind of green pasture outside the city,” Mogk says. “So, when Coleman Young is trying to exact promises from GM, when GM is not particularly interested in building in the city, you don’t have a lot of leverage.”

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to gaining more leverage, though, is not the developers but rather, the inherent appeal of development.

“The political and economic essence of virtually any given locality, in the present American context, is growth,” stated sociologist Harvey Molotch in an influential 1976 study, “The City as a Growth Machine.”

Vested interests including business, labor, and politicians of all stripes will, he wrote, always favor development and the jobs they promise. That’s why, despite the disaster the GM factory foretold for Poletown, it earned support from the UAW, along with the mayor.

Grunow recalls running into such sentiments when trying to get the city council to require a community benefits agreement for Little Caesars Arena. “Going into that vote, the carpenters, who on the surface would be on our side … came out very hard in support of the project,” Grunow says. “Because at that point we were potentially standing in the way of jobs.”

Ultimately, big developers might only be compelled to meet promises if citizens demand it.

“We gave up too much. We have to demand they don’t abandon us,” she says. “I think there’s the power of leverage. Power we haven’t used.”

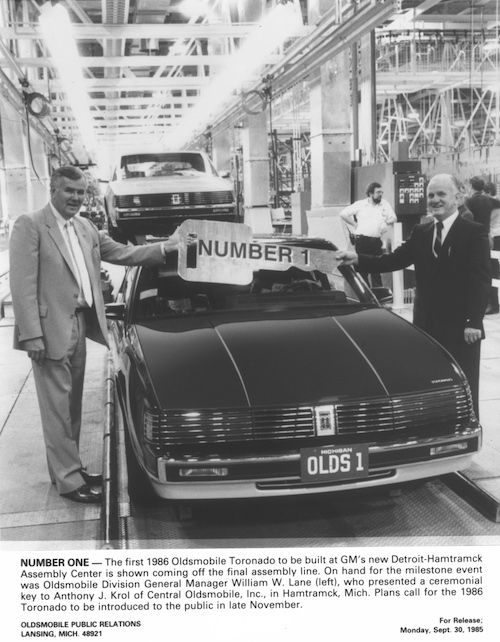

All photos courtesy of General Motors.