Parking lot Gerry

A portrait of a Detroit parking attendant who's been keeping vigil on the same block in New Center for the last 30 years.

From where he sits in his tiny booth on the north side of the Fisher Building, Gerry can see about half of a city block. Gerry is the attendant for Tony’s Parking on Lothrop Street. He has spent at least 60 hours a week here for the past 30 years, and he knows this place and its people with an alarming intimacy, though he is oblivious to what occurs just around the next corner. When I moved into the apartment building adjacent to the lot that is Gerry’s province, I had no idea that this outspoken parking attendant would have such a persistent, if minor, role in my life.

Above all else, Gerry is a witness to this neighborhood. His official territory includes only the parking lot, but his domain extends as far as his vision. He is the type of figure that Jane Jacobs would herald as the best kind of “eyes on the street,” with mutual trust, if not affection, on the part of the observer and its subjects.

Gerry arrives to work every day before 7 a.m. He calls “information” to make sure the time on his clock is perfect so no one can say he overcharged. He surveys the area, shoveling snow away from the sidewalk or sweeping puddled rainwater into the sewer. As people arrive, he files cars in rows according to the duration of their stay to maximize capacity and minimize block-ins. It’s an endless game of horizontal tetris.

“How long you gonna stay?” he says in his faintly antagonistic way. Gerry is so severely gruff that it’s almost endearing because he seems to care so little about what others think of him. In Gerry’s eyes, everyone has an agenda and he’s not in it. He preempts others’ dismissal with casual conspiracies about people who look at him the wrong way “I know what she’s about.” Gerry knows that the people who visit his lot aren’t there for him; they are there for a service. After a brief exchange of money and words, Gerry is left to watch people’s prized possessions, alone, like an underappreciated nanny.

Gerry is famous for his non sequiturs: “Good morning!” might be answered with “My life is more complicated than yours” or “Ain’t nobody else could do this job.” Sometimes he just repeats himself by way of extending a conversation that lacks momentum: “You gotta go? You gotta go now? Where ya going? You gotta go?” This elementary form of interrogation actually works to the point that Gerry is the keystone of gossip in the surrounding social landscape. (You’d be surprised how much personal information you give away when everything you say is answered with “what else?” five consecutive times.)

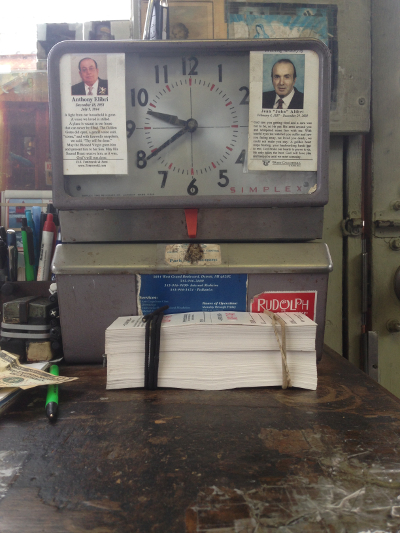

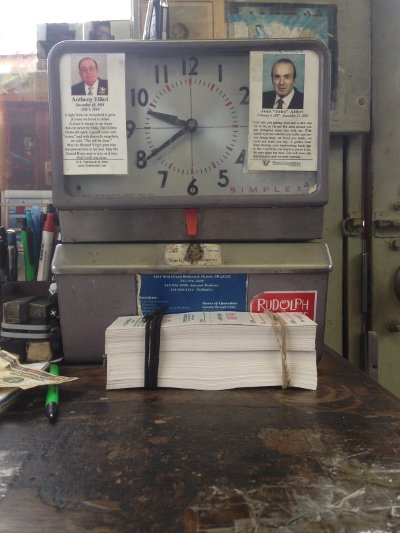

Gerry’s booth is about 10 feet square, with a porta-potty in the back. The interior is clean but worn, tidy but full. Everything has a purpose. Two walls contain pegboard grids of hooks for keys of valeted cars; their burdens wax and wane with the flow of traffic and the general economy of the area. The windows contain discreet mirrors that allow Gerry to surreptitiously observe whatever’s going on behind and beside him. There is a clock that sounds on the minute every minute with a slot to stamp the time on parking stubs as people check in and check out. There are baseball cards with Jesus on them sprinkled about – too many to count politely. There are small placards with photos and mini-eulogies from the funeral services of the former parking lot owner and his brother, immigrants whose last names were both assimilated to the New World, albeit differently (“Alibri” and “Elibri”). They taught Gerry Catholicism, Arabic, and how to run the business.

Gerry is fond of pointing out a gap in the ornate marble façade of the Fisher building that he watched crumble to the ground with his own eyes. He won’t walk on that side of the street to this day. Similar, though less dramatic, fascinating observations like this go on all the time.

The lot that Gerry manages holds about 100 cars and is filled by the daily traffic of people who are visiting the area to go to work, run an errand, see a play, or do whatever it is people do in New Center. When he started running things, however, the neighborhood was a different kind of busy. Just a block away, GM’s world headquarters provided vital fluid to the area until they moved downtown in 1996. In those days, Gerry fielded hundreds of cars a day, expertly maneuvering each vehicle to maximize the space in the lot without parking anyone in. Up until a few months ago, Gerry also controlled the lot for residents of the neighboring apartment building, but a new fence was put up.

To hear Gerry tell it, people try to dodge him in all kinds of ways. He calls it “playing psychology.” They sit in their car awhile before approaching the booth to see if they can slip by unnoticed. They hold cell phones to their ears and carry fake conversations to bridge the gap between car and apartment without having to interact with him. They visit the apartment at night and try to slip out in the morning without paying, but Gerry’s already at work, and he doesn’t give freebies to no Romeo. “That’ll be $5, was she worth it?”

Gerry is a prime example of small-town social politics in Detroit – its best to treat someone right, because you never know when you’re going to need them later. Gerry is called upon to help people who’ve locked their keys out of their apartment, who beg a favor for their guests when they have a party, who aren’t home when a package is being delivered, or who fail to notice that their back right tire is going flat. The benefits are many, but they are not meted out to those who don’t have the time of day to return the volley of rhetorical questions and small talk.

Sometimes I pick up coffee for Gerry at the donut shop in the New Center One Building. (They give Gerry a discount, which I find ironic because he is glued to his post so he can rarely can get it himself. )I like doing these things but, no matter how much time I give Gerry, I always leave feeling guilty. It’s as though my freedom is an affront to his fixation. I make conversation, I fetch the coffee, I give a friendly honk, but, always, it is I who leaves, not the other way around.

In this neighborhood, people have options for parking. There are the meters, a Russian roulette of parking fares – sometimes you can go for free if its out of service, sometimes it’s just a couple of quarters, other times you pay a sacrifice to the Parking God in the form of a ticket. Nowadays, you have to enter your driver’s license into the meter just to park, and not every Detroiter cares to alert the city to their whereabouts. There is a parking garage in the Fisher Building itself – once famous for its luxurious services including car detailing, gas-tank filling, and, of course, valet. It’s more expensive than the other options, the perks have dried up and not everyone seems to realize that “Detroit’s largest art object” is largely comprised of parking space. There is free parking with no meters just two blocks north of the Fisher, but most people don’t seem up for the walk.

Then there’s Gerry.

Gerry does not fear that his job will become obsolete, nor does he feel threatened by the changes afoot in the city. He knows that no machine can do what he does, and he’s right. It’s often easier to sail through the self check-outs in life and avoid human interaction, but don’t forget that Gerry will let you stay an extra 15 minutes without slapping down a $45 ticket. He will walk you through the ice between his booth and the sidewalk if you’re an old lady. He will tell you if you left your window down and watch out if you leave valuables in the car. He will tell you who left the flowers on your doorstep, and he will let you know if there are extra tickets to the show at the Fisher Theatre. Then he will almost spoil it all with some over-the-line comment about getting you pregnant, and then he will knock on the door with coffee the next morning at 6:30 a.m. by way of apology. He will let you know when a cat has escaped the 4th floor window, and he will chat with the cops about what’s going on down the block. He will treat you fairly and he will never be late.

The only real problem with Gerry is that he is human, too. He has feelings, which means that the cost of parking with him is slightly higher than the stated fare, and he has needs, which is why, every day, one of the spaces in the lot is reserved for his own car.