Michigan nonprofits are asking their communities to comment on maps for state redistricting process

We voted for this process so now we need to participate in this process,” says Norman Clement, founder of the Detroit Change Initiative, a member of the MNA coalition of nonprofits. As the public hearings near, read how Michigan nonprofits are helping their communities do just that.

Community Redistricting is a series about how Michigan communities are working together to end gerrymandering so that all residents have a voice at the local, state, and federal level. This series is made possible with funding from the Michigan Nonprofit Association.

Scrolling through the comments on the newly released draft maps from the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Committee and one thing’s for certain: Michigan has opinions. And community organizers want to see more of them.

When Michigan voters approved Proposal 2 in 2018, they elected for an independent commission of citizens to draw our voting districts, rather than our elected officials. Voters opted for a more transparent process, one that will, ideally, help solve issues of gerrymandering and underrepresentation. Over the past several months, residents have drawn and submitted their own maps to the commission. These are maps made by everyday people — perhaps not experts in redistricting itself, but certainly able to provide a wealth of knowledge about the communities in which they reside.

Last week, the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) released ten draft maps, ostensibly taking into account those maps submitted by the general public. There are three draft Senate maps, three draft House maps, and five draft Congressional maps, each named after a tree — Elm, Oak, and so forth — to help distinguish one from the next.

Now that the draft maps have been released, it’s time for the public to provide comment. That’s already begun to play out online, where residents can view the maps, select a district, and comment on its borders. A series of public hearings will take place in five cities beginning Wednesday, Oct. 20, in Detroit.

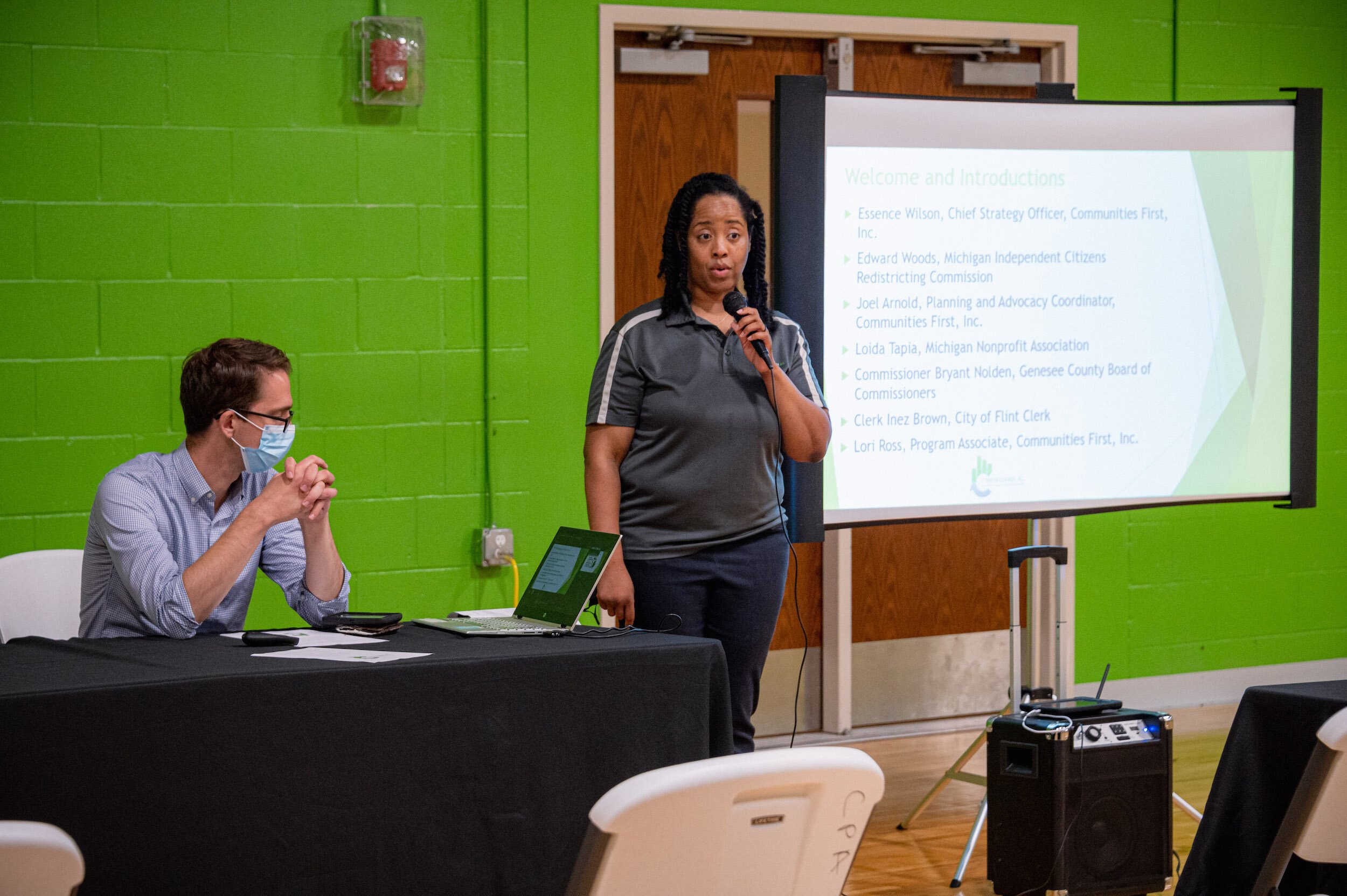

For Essence Wilson, co-founder of the Communities First, Inc. nonprofit organization in Flint, the message she’s been sending to her community is clear: Whether you hate a map, like it, or fall somewhere in between, just be sure to let the commission know what you think. That’s the important part.

“It’s really important that if there’s a map that people really like, we want them to comment and say that this is a great map, it represents my area well. That’s just as important as when people comment and say that, nope, we think you got it wrong and we want you to change this in a particular way,” Wilson says.

“That’s important because as the commissioners look at the comments, they need to know that not all people have a tendency to complain about the things they don’t like. But if we can affirm a particular map, then that goes a long way in letting the commission know that a community is in agreement with what’s been proposed.”

Communities of interest

Wilson’s Communities First, Inc. is one of 38 Michigan nonprofits that make up a coalition formed by the Michigan Nonprofit Association (MNA). The initiative has worked to organize underrepresented populations and provide them a stronger platform in the redistricting process. Each of the nonprofits represent a “community of interest,” a phrase built into the new redistricting law that, though loosely defined, gives voice to a group like, say, the Latinx community of Southwest Detroit.

The MNA initiative leverages the trust an underrepresented community might have in their local nonprofit to help get them involved in the redistricting process, a process that they might not have otherwise engaged.

“At every level of government, there’s disenfranchisement among minority communities,” says Hayg Oshagan, founder and director of New Michigan Media and associate professor of Media Arts & Studies at Wayne State University.

“From the political system to the political process, there’s a level of mistrust or a lack of trust. And all of that affects any project that comes around that has to do with political participation. Whether it’s voting for something, whether it’s the census, or whether it’s redistricting, these are all issues to overcome in these communities.”

Under the new redistricting law, identifying as a community of interest helps to strengthen a community’s efforts to represent themselves as one district, rather than the multiple districts that they may have been split into in the past. They are then that much more likely to have a representative that responds to their needs.

Preparedness is key

The maps Wilson submitted as part of the MNA initiative identified the city’s majority-Black population and its North Flint neighborhood as communities of interest, communities that have experienced significant disinvestment over the years. Those maps submitted aim to ensure that those communities are properly represented in the new political districts, something that Wilson says isn’t necessarily the case in some of the draft maps recently released by the MICRC.

“Some of that has been reflected in some of the draft maps. But there’s also some concerns in those drafts, as well,” Wilson says. “There is quite a bit of concern about the 34th district — one of the maps showed it physically not existing. And that’s been a majority-African American district so folks have expressed a good amount of concern about that.”

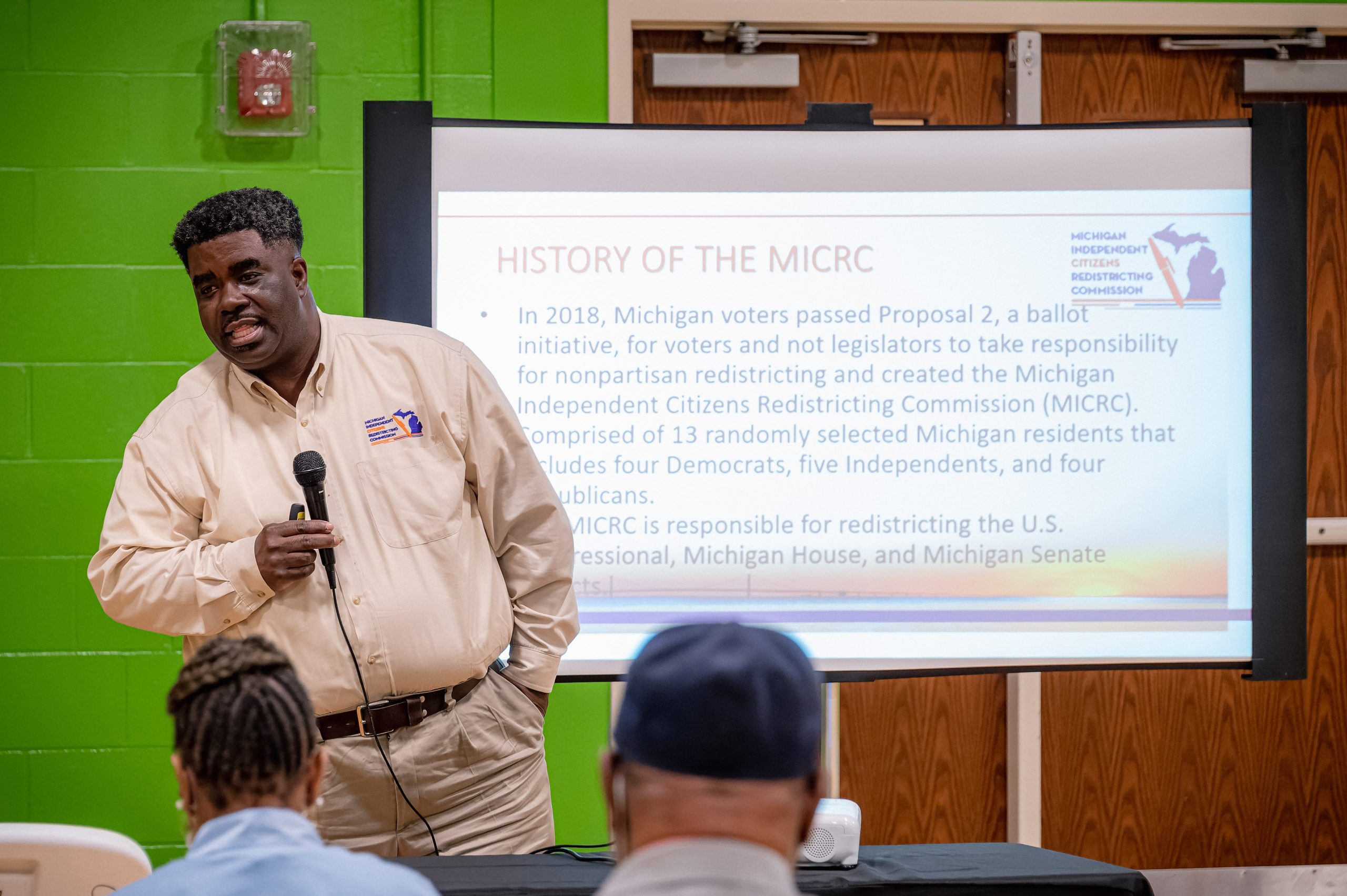

To further express that concern to the commission, Wilson and the team at Communities First, Inc. have been working with members of their community, not only directing them to the online comment portal but also providing information on what the maps represent and why that’s important. They hosted an informative workshop on Oct. 7, where they prepared guests on how to provide public comment.

The public hearing in Flint is scheduled for Tuesday, Oct. 26, at the Dort Financial Center. Outreach efforts from Communities First, Inc. have included reaching people by email, social media, flyers — whatever it takes to get the community commenting on these draft maps.

In addition to encouraging people to comment, Communities First, Inc. has also been assisting their neighbors in how to comment. Because each person attending the public hearing will be allotted just 90 seconds to comment, preparedness, Wilson says, is key.

“We’re providing tips and tricks to folks: they need to be aware of the time, they need to write out their comment, practice it. If they can’t summarize it in 90 seconds, they could also provide written comment, where the information can run a little bit longer. They could also comment online on those maps,” Wilson says.

“So we’re encouraging people to comment and participate in multiple ways to make sure that their message doesn’t get lost in the shuffle.”

Barriers remain

While the new system for redistricting may be more transparent and citizen-driven than in decades past, it hasn’t been without criticism. The redistricting process has been running behind schedule — something that officials attribute to delays in receiving U.S. census data, which itself has been blamed as a byproduct of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the ways in which the commission has made up for lost time has been to reduce the number of statewide public hearings from nine to five, cutting planned hearings in Kalamazoo, Marquette, Novi, and Warren. The closest hearing to Kalamazoo is now in Grand Rapids. With Marquette’s event canceled, which was the only public hearing planned for the Upper Peninsula, residents there will now have to drive to the northernmost public hearing planned for the Lower Peninsula, which is in Gaylord.

As the Novi and Warren public hearings have been cut, that means that the only public hearing planned for metro Detroit will be in the city itself, scheduled for Wednesday, Oct. 20, at the TCF Center. With everyone guaranteed their 90 seconds, it could make for a long night: Metro Detroit is home to roughly 40 percent of the state’s population yet only has one public hearing to show for it.

“I wish that the commission would add another day of public hearings for southeastern Michigan. It doesn’t even have to be in Detroit. It could be in Novi, it could be in Pontiac,” says Norman Clement, founder of the Detroit Change Initiative, a member of the MNA coalition of nonprofits.

“I feel that Oakland County and Wayne County especially need at least two days of hearings because those are the most populous counties and when the maps are drawn, those are the counties most heavily impacted. At the upcoming hearing, you go through the last speaker and it could go well up to two or three o’clock in the morning.”

In addition to attending the in-person public hearings, Michigan residents can provide comment at the meetings via phone or Zoom. Beyond the time constraints of the hearings, residents can also submit their comments online, through the portal or the draft maps themselves, and by mail.

Those may be more preferable options for many, though issues like barriers to technology or language could further limit people’s ability to provide comment. Organizations like the MNA, Communities First, Inc., and the Detroit Change Initiative are helping to knock down some of those barriers.

And that’s important. Even if you are the last person in line at the TCF Center at two o’clock in the morning.

“We voted for this process so now we need to participate in this process,” Clement says. “We fought to put this on the ballot and we overwhelmingly voted to have our own commission. So now we have to participate in that commission.”