From glorious to inclusive: The past, present, and future of Detroit’s LGBT spaces

In the '70s and '80s, Detroit had a strong and proud gay presence with a hub in Palmer Park. While that "gayborhood" no longer exists, the city is steadily reclaiming its LGBT heritage, and becoming more inclusive as a result.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Jeff Montgomery, longtime Detroit LGBT activist and founder of the Triangle Foundation, which worked to combat anti-LGBT crime and discrimination nationwide. He died last week.

In the aftermath of last month’s attack on Pulse in Orlando, many LGBT people took time, amid our grief, to reflect on our experiences in gay bars, the spaces we’d always thought of as “safe.” We wrote or posted on social media about our first gay bar, about the thrill of being suddenly surrounded by people like us, about dancing until 4:00 a.m. We discussed how our communities were built and sustained in these spaces. We talked about the clubs that have come and gone, and the ones that have persisted. Our conversations were something good that emerged from something horrific. They presented opportunities to celebrate and honor a part of our culture that we might otherwise take for granted.

The notion of the “safe space” dates back to the women’s and gay liberation movements of the 1970s. And while the murderous rampage at Pulse reminds us of the literal physical danger that so many in the LGBT community still face, “safe” in this context also means something other than safe from the threat of violence. It means safe to be yourself, to express yourself—or, perhaps, to express parts of yourself that you might hide in other places. Safe to touch someone you care about without worrying who might see, and what they might say or do if they did. It means being released from the otherwise unblinking gaze of what we have learned to call heteronormativity: the destructive, socially reinforced illusion that “straight” is good and right and true, while “queer” is wrong. A secret. A shame.

While LGBT Americans have made great political strides in recent years, the need for our own spaces has not diminished. Not only have those advances been unevenly distributed among our people, many of us still face discrimination (some of which remains enshrined in law in Michigan), as well as isolation. And let’s face it, even if all of us get all of the rights to which we’re entitled and feel 100 percent socially accepted all the time, we’re still going to want to spend time among our own people, our queer family, with whom we’ve shared so much.

“Glorious” Palmer Park

In Detroit, many LGBT people will tell you that we don’t have as many spaces in which to be our full and authentic selves as we ought to. But the folks who’ve been around for a while will remind you that this was not always the case. In the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, there were an abundance of spaces within the city limits that gay and lesbian people thought of as their own. (Back then, it was “gays and lesbians”—I don’t think people with bi-attractional tendencies were taken very seriously, transgender people were even more misunderstood and marginalized than they are today, and “queer” was still just an insult, not a proudly reclaimed declaration of sexual nonconformity)

Lifelong Detroiter Gary Eleinko—who, when I ask him what year he was born, rolls his eyes and tells me to “just say 1950″—remembers a lot of those places. When I meet him at his Corktown home to learn about the city’s gay history, he presents me with a prepared list of about 30 now-closed establishment that he frequented over the decades that catered to a largely gay clientele. His first gay bar was the Woodward, which, happily, is still around (these days, the crowd is primarily black; back in the early ’70s, it was mostly white). Eleinko describes the feeling of walking into the crowded bar as “magical, mystical, mysterious. Just to see all those gay people, to realize there were so many!”

Between 1972 and 1982, Eleinko lived in Palmer Park, Detroit’s fabled gay neighborhood. He recalls this time, when there were “easily a dozen gay people” in every apartment building, not to mention a smattering of busy, walkable, gay-friendly bars and restaurants, as “glorious,” and says that most of his friends today are people he met there.

But Palmer Park declined over time, for complex reasons that are intertwined with the wider city’s reversal of fortune: some mix of disinvestment, crime, racial tension, and the siren song of the suburbs and other major metropolitan areas. Today, the neighborhood remains home to both the popular gay bar Menjo’s, as well as Hotter Than July, the annual gay black Pride festival that’s taken place there since 1995, but it’s hard to think of Palmer Park as a functioning “gayborhood” much after the ’80s; it lacked commercial vitality and queer population density, both of which largely went the way of the people who chose to move out.

Broadening the umbrella

In the years since, a variety of queer spaces have continued to operate throughout the city, but they’ve tended to be far-flung and physically nondescript, de-centering and reducing the visibility and vibrancy of the LGBT population that has remained.

Robbie Dwight, 27, who was also born and raised in Detroit, doesn’t fault the queer folks who chose to leave under these circumstances. “Why would they stay here and struggle when they could go somewhere else and immediately set up shop?” he asks. “I have a very strong will. I’m from here, I want to stay here, I have a vested interest. But it’s sort of irrational to put that expectation on someone else, because it’s a lot of work!”

To Dwight, who leads an inclusive, LGBT-friendly fitness class every Sunday morning at Proving Grounds Strength and Konditioning, our relative lack of spaces is a self-fulfilling prophecy: “As a major metropolitan area, we haven’t done enough for our community. We don’t have enough spaces—but we also don’t have the clientele to support them.”

And while more and more LGBT people do seem to be riding the revitalizing wave back into the city, Dwight worries that we’re still not doing enough to integrate and uplift our diverse communities, pointing to the “internalized racism and xenophobia” that continue to keep us apart.

The LGBT umbrella is broad, and it’s true that the communities that gather beneath it have long had a tendency to stick to their own. The queer history of Palmer Park, for instance, is largely a story of gay white men, not lesbians, people of color, or transgender people. But, Dwight argues, “It’s a very different world now than it was in the ’80s, ’90s, or even early 2000s. I really think more than ever, we need to start collecting together and making this one big machine that advocates for not just every color in the rainbow, but every flag we identify with, for every letter of LGBTQ plus. It’s a time when we need to say, if all of us aren’t getting equal rights, then none of us are.”

Curtis Lipscomb, 51, founder of Hotter Than July and executive director of education and advocacy nonprofit LGBT Detroit, echoes Dwight’s sentiment. “Just because I’m OK,” he says, “doesn’t mean that everyone’s OK.”

When I ask him to reflect on the diversity within the LGBT community, he says, “As a gay man, the issues that would affect me are different than the issues that would affect my sisters who are lesbian, my trans brothers and sisters, and my bi brothers and sisters. They just are. But we do band together because we’re treated in a similar way by law. And so I celebrate our differences, and I celebrate the fact that we’ve learned to coexist because of the things that unite us.”

Lipscomb, who grew up in Detroit, is in a celebratory mood. That’s because LGBT Detroit has just taken a big step toward creating a new safe space in town that will continue their work of advocating for and uniting queer Detroiters and our allies; they’ve purchased a building, a formerly vacant, one-time dentist office in northwest Detroit that they’re converting into a brand-new LGBT community center, a place for conversation, resources, support, and learning.

On the day of my visit, Lipscomb and I meet outside the building, on Greenfield just off the Lodge, and he periodically jumps up from our conversation to supervise a work crew. He’s excited, not just because of the fact that his organization is getting its own home, but because that home is in a Detroit neighborhood.

“Everyone’s talking about getting out into the neighborhoods,” he says, referring to the looming question in Detroit of how the current revitalization can uplift the whole city, not just the handful of places in which development is currently concentrated. “Well, we’re in a neighborhood, and we’re leading in this area of developing outside the two or three specific places that people would expect. We’re bringing some attention to this under-acknowledged area, and I’m excited about the possibilities.”

For Lipscomb, the fact that Detroit no longer has a gayborhood is an opportunity, not a liability. It means that LGBT people here are integrated, and that as a result, we have the chance to work within the wider community to forge mutually beneficial alliances. Lipscomb has lived in a gayborhood, on Christopher Street in New York City, and while he has fond memories of those days, he’s also come to think of it as “Disneyland—and I don’t mean that in a good way.”

“Let me be clear,” he continues, “I love being around my queer brothers and sisters. But how can you fight for equality when you live separately? How can you change hearts and minds if you live in an isolated world? How can straight folks march with us if they don’t even know us?”

An inclusive future

I found myself reflecting on these questions of inclusion and integration at two different events in recent weeks: a picnic on Belle Isle organized “for homosexuals and friends,” and the latest incarnation of Macho City, an itinerant, eight-year-old queer dance party that’s taking place every Saturday night this summer on the upstairs patio of Briggs, a new-ish gay sports bar downtown.

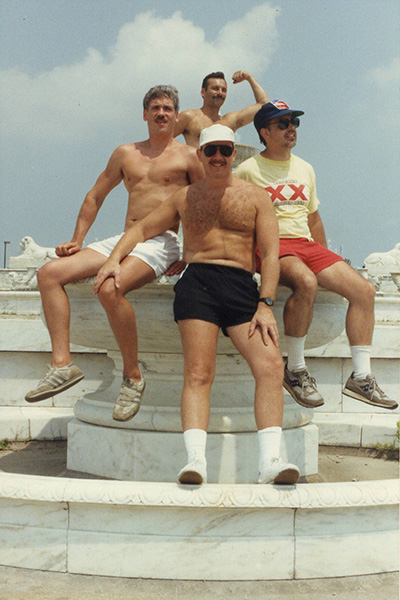

Both are contemporary iterations of events I’ve been attending in Detroit, off and on, for nearly a decade. (And both have local precedents that reach much farther back than that; Gary Eleinko remembers the ’70s and early ’80s in Detroit as the time of Mannis, a jam-packed disco club on Holden St., as well as “huge gay picnics” that took place—where else?—on Belle Isle.)

The two recent events were well-attended by habitués and new folks alike, and there was a palpable feeling, at both, of the old magic, that exhilarating sense of queer camaraderie and belonging.

But there was something different, too. The people, notably, didn’t all look the same. The assembled groups weren’t monolithic in terms of ethnicity, sex, or gender expression. Instead, it seemed that very different kinds of people were getting together and choosing to make good on what Robbie Dwight thinks of as one of the unexpected gifts of heteronormative culture: “As a queer person, once you meet another queer person, they’re family. Someone you know. Someone you can trust.”

The diversity on display at Briggs and at the picnic, along with the development of LGBT Detroit’s new Northwest headquarters, are heartening signs of the times. They point, perhaps, to a future in which Detroit is full of places where LGBT people can set aside our differences and come together, be ourselves, be visible, organize, and engage with the communities around us.

Our work, however, is far from done. For now, we need more of those places—not to mention more kinds of places, more people to use them, and more leaders to catalyze their development. But as we continue to build that better future, we would do well to remember that we’ve come a long way to get where we are now. And that, even if we sometimes have to dig a little to find them, our roots here are deep.

Hotter Than July takes place July 35-31 at and around Palmer Park. Macho City takes place every Saturday this summer from 9 p.m. – 2 a.m. at Briggs Detroit. The Belle Isle picnic happens on Sundays from 1 p.m. – 10 p.m., just past the lighthouse; remaining dates are 7/31, 8/14, 8/21, and 9/4.

All photos, except “Friends on Belle Isle,” by Matthew Piper.