This Dearborn Heights resident is helping non-English speaking voters bring power to their voices

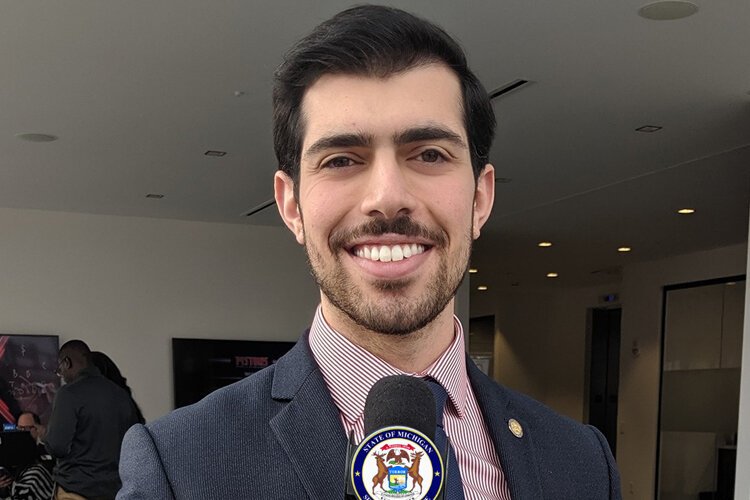

Model D caught up with Bilal Hammoud, public engagement associate with the Michigan Department of State, to ask about voting access and how it feels to be able to raise the voice of his own community on a statewide level.

Bilal Hammoud serves as the public engagement associate for the Michigan Department of State (MDOS). Appointed in 2019 by Jocelyn Benson, the second generation Lebanese American is the first Arab American to serve inside the Executive Office. During COVID-19, Hammoud created the Language Access Task Force aimed at removing barriers that detour limited English proficiency (LEP) communities from voting.

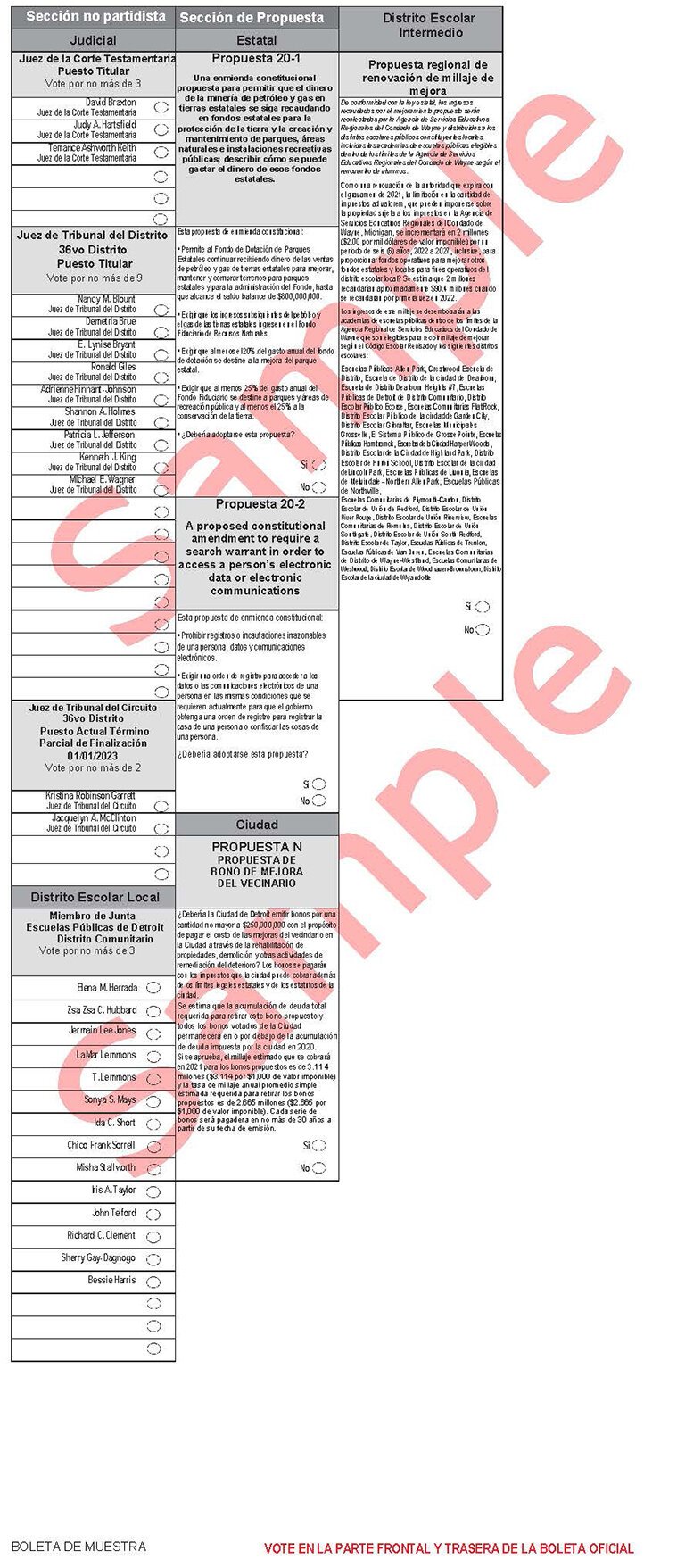

This includes creating and distributing voting materials in nine languages among LEP communities statewide. He also launched a pilot program in five different communities: Southwest Detroit and Hamtramck as well as Dearborn, Pontiac, and Grand Rapids, translating sample ballots in Spanish, Arabic, and Bengali.

As public engagement associate, he leads outreach with marginalized communities, including “returning citizens, housing-insecure individuals, and the LEP (Limited English Proficiency) community, where we’ve used our language access programs to support our immigrant and refugee populations,” he says. He also conducts voter education town halls and student drives as well as develop partnerships with stakeholders and organizations across the state.

Prior to his role at the state, Hammoud, 24, worked as community engagement liaison with Forgotten Harvest, project manager for the city of Cheboygan and community relations manager with Communities First.

With Tuesday’s election looming, Model D caught up with Hammoud to ask about voting access and how it feels to be able to raise the voice of his own community on a statewide level.

Model D: What work have you been doing in the Language Access Task Force?

Bilal Hammoud: I created this task force just after the pandemic hit as a way to expand I.D. and branch services to LEP communities. But as the election drew closer, we focused our lens directly on creating, translating and distributing voting materials: voter registration forms, absentee ballot applications, toolkits and videos, all of which is accessible on our website.

This task force is one of the first of its kind in Michigan and in the country. Under the guidance of Jocelyn Benson, we’ve partnered with more than 50 organizations across the state that work with non-English speaking communities, and been able to distribute voting materials in nine languages: Spanish, Arabic, Bangla, Burmese, Mandarin, Tagalog, Hindi, Korean, and Urdu. We’ve streamed statewide events in these languages and connected with communities through social media, WhatsApp, group chats, Facebook groups, and with media and radio that works with non-English speaking communities including New Michigan Media.

Model D: Who are some of your local partners in the Language Access Task Force?

Hammoud: Asian Pacific Islander American Vote (APIAVote), Global Michigan, Global Detroit, ACCESS, Labor and Economic Opportunity (LEO), and Michigan Voice. We also partner with local leaders like Councilwoman Raquel Castaneda-Lopez from Detroit who has been a big part of this movement and instrumental with her immigration task force.

Model D: Why is creating this type of access for people important to you?

Hammoud: The idea of empowerment is important to me. I come from the Arab American community and I know how tough it is to not be recognized. We’re not on the Census. So we’re not federally protected, our jobs aren’t federally protected, there aren’t grants or research for my community.

Yes, protections by the Federal Voting Rights Act gives power to some LEP communities by mandating that cities translate if a language is spoken there among a minimum population of 5%, but because Arab Americans aren’t on the Census, we aren’t given that right. Even in Dearborn, where 50% of the population is Arab American, we don’t see those services being offered. I’m excited because this program isn’t just a step toward accessibility — it’s giving power to voices who haven’t been catered to by their state, their community. They should be given the tools necessary to practice their democratic right as citizens.

Model D: How did you navigate translating materials accurately for our region?

Hammoud: Coincidentally, the task force was created in part because we received a complaint in Hamtramck about accuracy in the Bengali language. We looked into it and saw that translations were coming from a one-stop shop — you send the stuff and they translate it into any language and format. I realized this wasn’t an accurate way to do localized translations. So the task force initially worked to translate official state documents to ensure that people could get information in the languages they need.

In response to that complaint, we partnered with APIAVote to translate our APIA languages including Bengali. They have their own team of certified translators. Now we make sure everything we do goes through the entire task force to allow all expertise to be heard. For the sample ballots, we conducted interviews and chose the organization with the best formatting and language accuracy. The whole process helped us connect on a deeper level with organizations and most of them have joined our team.

Model D: Will sample ballots be available in all nine languages?

Hammoud: This is just a pilot program with minimal resources, so we’ve focused on five municipalities: Pontiac, Grand Rapids, Southwest Detroit, Dearborn and Hamtramck. In Detroit and Grand Rapids, we’ve done sample ballots in specialized precincts. In the other three, we’re covering the entire city. The ballots are translated in Spanish, Arabic, and Bengali as needed, and we derived these languages with a data driven focus by looking at population, voter propensity, and languages centralized around polling locations.

We’re thankful that many clerks are on board for this. It’s a huge help for people to see ballots at their polling locations. They can also reference it on our site while filling out an absentee ballot or while voting in person if it is not posted. In addition, we’ve worked with our partners to recruit 250-plus bilingual poll workers to ensure the municipalities we’ve highlighted with large LEP populations are receiving the resources they need to succeed.

Model D: Do you plan to expand this program to cover more communities in the future?

Hammoud: I feel confident in the success of this program. We want to lobby that success into future funding and potential translations. I’m honored that I’ve been able to lead all of our language access services, lead the task force and make this available. I’m excited for the future because if we could do this much with minimal resources—and a lot of the restrictions we’ve had in funding comes from the pandemic and restricted state spending—imagine what we could do with a fully funded initiative behind this.

Model D: Are you surprised at how much you’ve accomplished at the age of 24?

Hammoud: I don’t think I’m breaking barriers when it comes to age. There are people younger than me who have accomplished more. I do appreciate the opportunities that have been provided to me and the environment my parents have created for me. I think the big thing behind the age factor is that sometimes people immediately want to jump to that to determine your level of success, but I never let it be something that defined me.

I am thankful to be able to lead in this sort of work at my age. This administration really opened up that opportunity, along with the partnerships and colleagues I’ve been able to develop throughout my career across the state. Anything I’ve accomplished is only because I was able to bring those relationships into my work. Then I was able to bring my community into the fold.

Model D: What does it mean to you to be the first Arab American in the Executive Office?

Hammoud: Being Arab American is something I take a lot of pride in. I’m thankful to have grown up in a community like Dearborn and Dearborn Heights where I get to see my culture around me. But I also spend time in other communities and see how little representation there is for my people. So when Jocelyn Benson appointed me to this position, I was absolutely honored. I get to stand as a representative of my community, my culture, and tackle the issues I think are important. Thankfully, this administration was built around the ideas of innovation and proactivity in our work so I’ve been able to really actualize my ideas as you’ve seen through the Language Access Task Force and a lot of our other initiatives.

I’ve spent a lot of my career focused on accessibility, trying to bridge a gap between government and community. I’m grateful to get to put the knowledge I’ve gained to work on a statewide scale.

There are people who’ve laid down the framework for me to be here and have made us a community of interest and focus. Elected officials like [U.S. Representative] Rashida Tlaib and [State Representative] Abdullah Hammoud bring power to our voice and consistently push the norm and the conversation. Abdul El-Sayed is a great example of someone who’s just been steamrolling the idea of Arab Americans and health and research. He served as a role model for the beginning of my career, demonstrating the potential we have to sit at the table. I think it’s important that we find a seat at the table, at every table, so we have representation at some level. I know if we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu.

Model D: What do you want to tell voters who’ve been discouraged by our voting systems?

Hammoud: Bring power to your voice. Bring power to your community. You’re not just voting for yourself, you’re voting for your neighbors, for your friends, and for your culture. If you want the Arab American community to be looked at, if you want your community to be looked at, catered to by the electeds chosen, you need to vote. Even if you are discouraged by the system, even if no one there represents you, you need to vote so that someone there will represent you, and that you’ll be a voice and a source of power.