HISTORY LESSON: The right-wing radio mogul who gave the Lions to Detroit – and revamped Thanksgiving

The same year that a leading right-wing station was receiving 10,000 letters of fan mail daily, its owner bought the Portsmouth Spartans, a struggling small market NFL team in Ohio, and moved them to Detroit.

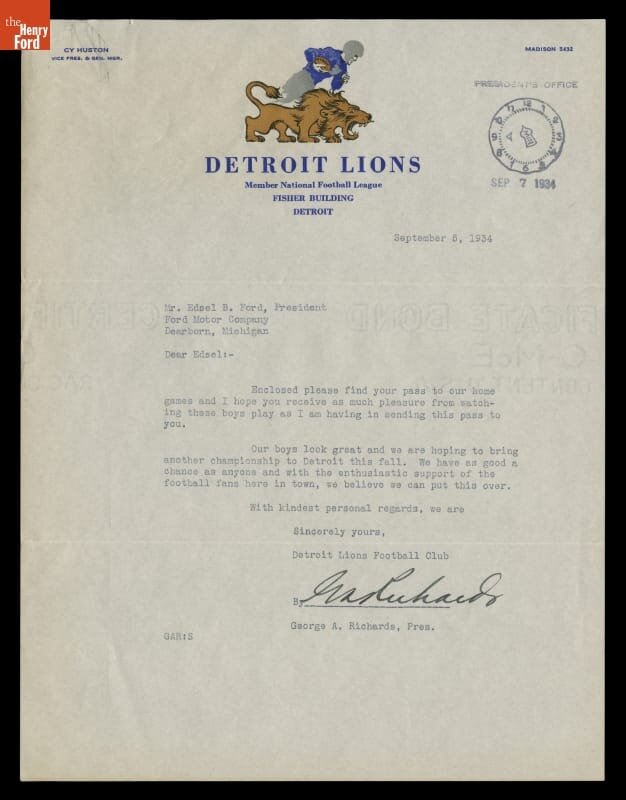

When George A. Richards bought the Portsmouth Spartans and moved them to Detroit, he had big plans. He was convinced that he was the man to take the NFL to the big stage. But he was going to have to be creative.

The good news for the league and for the team is that Richards had experience. Making a fortune in the auto industry, Richards then turned his sights to the radio business. He purchased Detroit’s WJR in 1929 and in 1930 consolidated Springfield, Ohio’s WSCO and Akron’s WFJC into a Cleveland-based station humbly named WGAR (his initials).

The stations would become some of the most powerful and popular in the country, largely in part because they all platformed America’s leading right-wing and antisemitic voice broadcasting live from the Detroit suburbs: Father Charles Coughlin.

Coughlin, the head priest at the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, had begun broadcasting weekly radio shows on WJR in 1926. But as his broadcasts became increasingly controversial, CBS demanded to approve his scripts before broadcasts. When Coughlin refused, CBS dropped him. But Richards was there to pick him up. A full-fledged antisemite and reactionary in his own right, Richards helped Coughlin go independent and encouraged him to drop most of the religion from his shows opting instead for increasingly right-wing politics. It worked.

With the financial backing of Richards, Father Coughlin became the nation’s first political radio star. His weekly broadcasts we’re listened to by a staggering 30 million people, roughly 25% of the American population. It made Richards a fortune and taught him an important lesson: You no longer needed to get people in a room with you to influence them, you could make reach them better than ever before through the radio.

Richards would bring this lesson to the NFL.

In 1934, the same year that his star talent Coughlin was receiving 10,000 letters of fan mail a day, Richards bought the Portsmouth Spartans, a struggling small market NFL team in Ohio, and moved them to Detroit.

Now rechristened as the Detroit Lions, the team got off to a hot start under the direction of head coach Potsy Clark and quarterback Dutch Clark (no relation), and were in contention for the Western Conference Championship. But the Lions were struggling to draw fans to their home stadium. In Detroit, in a town where baseball was king and the Tigers were in a pennant chase, the Lions were hardly ever able to steal away newspaper columns. Richards needed to make a splash.

And make a splash he did. Richards scheduled a game against the leading team at the time in football, the Chicago Bears, on Thanksgiving Day. The rationale was simple, people weren’t doing much on Thanksgiving, maybe they would be willing to attend a football game.

He was right. When the Bears and Lions took the field on November 29, 1934, they were surrounded by over 26,000 fans, a record number for a professional football game in Detroit. Another 25,000 were turned away at the gate. The Lions donated the funds raised through ticket sales to charity. They didn’t need the money.

Richards, the master of radio, knew the real value would be found elsewhere.

Thanksgiving, a day in which families hung out together at home, would be the perfect time to expose the country to a national radio broadcast of NFL football. Using the cache, he built up broadcasting Coughlin, Richards convinced the NFL and NBC to broadcast the game on 94 radio stations nationwide. Families across the country would have the Lions and Bears game broadcast directly into their homes. It was the birth of an American Tradition. Aside from a six year stretch during WWII, the Lions have played at home on Thanksgiving every year since and have been broadcast nationally on TV since 1953.

But Richards wouldn’t be a part of it. Although the Lions would win the championship in 1935, Richards was widely considered to be a poor owner and ultimately sold the team in 1940 for $200,000. He had fallen ill and claimed he sold the team on the advice of his doctors. But rumors persist to this day that he was forced out due to nefarious actions, including gambling on games.

Richards would spend the final 11 years of his life in court. Employees of his stations came told congress that his radio stations were rife with antisemitism, racism, political bias, and paranoia. He killed negative stories about Douglas MacArthur, claimed that his rivals at CBS were part of a “Jewish plot” against him, and mandated to his staff that “the CIO, Negroes, Jews, the Roosevelt family, and the New Deal never be presented in a favorable light”

On May 15, 1951, the FCC recommend that Richards’ stations should be shut down. He died 13 days later. Father Coughlin attended his funeral.