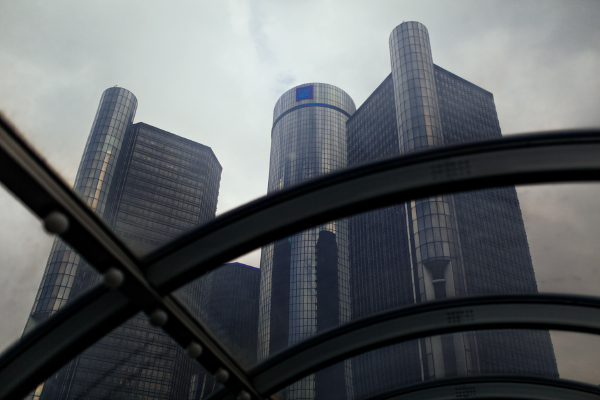

HISTORY LESSON: A sympathetic look at the Renaissance Center’s architect, John Portman

Welcome to History Lesson, a new recurring feature in Model D led by local historian Jacob Jones, in which we delve deep into the annals of Detroit history and nerd out over a different topic each time. This month, we’re talking about the RenCen.

John Portman is back in the zeitgeist.

When General Motors and Bedrock announced plans to tear down two of the Renaissance Center’s towers, a fresh crop of John Portman – the architect who designed the skyscraper in the 1970s – hate bloomed in Detroit.

Portman criticism is nothing new in some local circles. He’s long drawn the ire of commentators in the various Detroit architecture Facebook groups who treat him like something between a dog and a war criminal. But this time around, Portman critics are seemingly popping up all over the place.

Earlier this week, while aimlessly scrolling on Twitter, I spotted a post about Portman. Architecture Tradition (@archi_tradition), one of a score of anti-modern architecture bros on the platform, asked his 708,000 followers: “What is the ugliest building you’ve ever seen?” (His choice was Portman’s San Francisco Hyatt Regency. It had 2,000 retweets and hundreds of agreeing replies.)

Portman’s detractors, at least in this town, usually focus on aesthetics. His Renaissance Center was built two generations after Detroit’s architectural heyday and a generation after its mid-century modern mini-boom. It stands in stark contrast not only to the Guardian and Penobscot Buildings or the Book Tower, the icons of Downtown Detroit’s pre-war architecture boom, but also to One Woodward and City Hall of the 1950s and 1960s. It defines the city’s skyline, not because it compliments what came before but because it revolts against it. And for this reason, many hate it.

But it’s why I love it.

I’ve spent a decade leading tours of Detroit. I’ve taken thousands of people through the Fisher Building, the Guardian Building, and around Downtown Detroit highlighting our architectural marvels. And on most tours, I can count on at least one person pulling me aside to bemoan the Renaissance Center and Portman. They assume I’ll agree. I don’t.

Portman lived in a very different world than ours. His was not one that saw investment back into cities, but one reeling after decades of disinvestment and suburban sprawl. Businesses moved to the suburbs and brought their jobs with them. The people followed. They moved to cookie cutter neighborhoods, worked in cookie cutter office parks, shopped in cookie cutter malls, and watched games in cookie cutter stadiums. Portman broke with this trend.

Portman chose to invest his time and efforts into America’s cities. “I think our democratic system depends on what we do with our cities.” Portman told the Detroit Free Press in 1971. “If we go off and leave large pockets of discontent, we may find the house is on fire.”

Portman built the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, the Bonaventure in Los Angeles, the Marriot Marquis in Manhattan and scores of other developments in urban areas across the country. His atriums were the building’s defining features. The Renaissance Center’s atrium, which now looks like a suburban shopping mall combined with an auto dealer’s showroom, was at one point a remarkable combination of neofuturistic design, brutalism, and greenspace. Plants were seemingly growing right out of the atrium’s concrete columns and walkways. It was unlike anything else in town.

I’m not here to defend the Renaissance Center as a development. By all accounts it was a mistake. It was born out of a paternalistic view of Detroit. Portman and his benefactor’s solution to the city’s problems was a landgrab. From a planning perspective, it was a disaster. The lifeblood of a city is its street level activity, and the Renaissance Center pulled that activity out of greater downtown and tried, unsuccessfully, to replicate it in a single megastructure.

The New York Times’ architecture critic would say of Portman’s buildings that “the architect seems interested in urban activity only insofar as it can be canned and packaged within its walls”. Portman was much more concerned about what was happening inside his buildings that what was happening outside of them.

In a perfect world, the powers that be who funded the Renaissance Center would have had a modern urbanist view of our city. They would have focused on the street level activity of downtown Detroit. They would have invested in transit and housing and people. They would have poured money into restoring our historic structures. I think we would all much rather have a dense rivertown neighborhood filled with housing, commercial activity and greenspace ala Pittsburgh’s Strip District.

But this wasn’t a perfect world and Portman did the best he could. He built Detroit the world’s tallest hotel, he broke the Penobscott Building’s half-century reign as the tallest building in town, he created a building unlike anything else on the planet at the time, and he redefined the city’s already remarkable skyline. W. Hawkins Ferry, arguably the city’s preeminent architecture historian and critic, wrote in the revised edition of “The Buildings of Detroit” (1980), of the Renaissance Center:

“After a period of disillusionment, Detroiters may now look forward to a brighter future in which the suburbs will complement and reinforce the central city instead of draining it. The central city will remain the commercial, financial, professional, and cultural hub of the metropolitan area…”

Portman understood that Detroit, a city filled with iconic buildings from previous generations, deserved an iconic structure for a new generation. I hope we’re able to remember that if some or all of its towers do meet the wrecking ball.

Jacob Jones is a historian and storyteller who has spent a decade leading tours of the city’s iconic landmarks. His tours of the Fisher Building, Guardian Building, and Packard Plant have attracted tens of thousands of guests from around the world and have been praised by the Detroit Free Press, the BBC, and the New York Times. When he’s not sharing history you can find him in a good local bar, perusing the stacks at the Detroit Public Library, and cheering on his beloved Detroit Lions.