Gentrification?

The increase in development and re-development in Detroit has sparked talk of the “G” word. But does gentrification in Detroit mean the same thing as it does in other major cities?

The signs are everywhere. Start with pockets of residential and commercial activity along East Jefferson and zero in on dozens of high-rise housing developments in the heart of downtown. See projects promised, in progress or completed in Midtown, a 21st century Detroit neighborhood anchored by the Wayne State University campus, and the cultural and medical centers. Go a bit further west into Corktown, then dip into Southwest Detroit, where some of the city’s oldest buildings are being face-lifted and restored, mirroring the increasing amount of life visible on the streets.

What do some of the signs say? “Reinvent Your Life: Reinvent Detroit” is attached to a message board on Canfield pitching Midtown Development’s new housing units at Willys Overland Lofts around the corner on Willis.

What do some of the signs say? “Reinvent Your Life: Reinvent Detroit” is attached to a message board on Canfield pitching Midtown Development’s new housing units at Willys Overland Lofts around the corner on Willis.

Another sign advertises the Centurion Place development on Ferry Street, with this equally bold declaration: “Rebuilding History: Luxury Custom Brownstones in the Heart of Detroit’s Historic Cultural Center.”

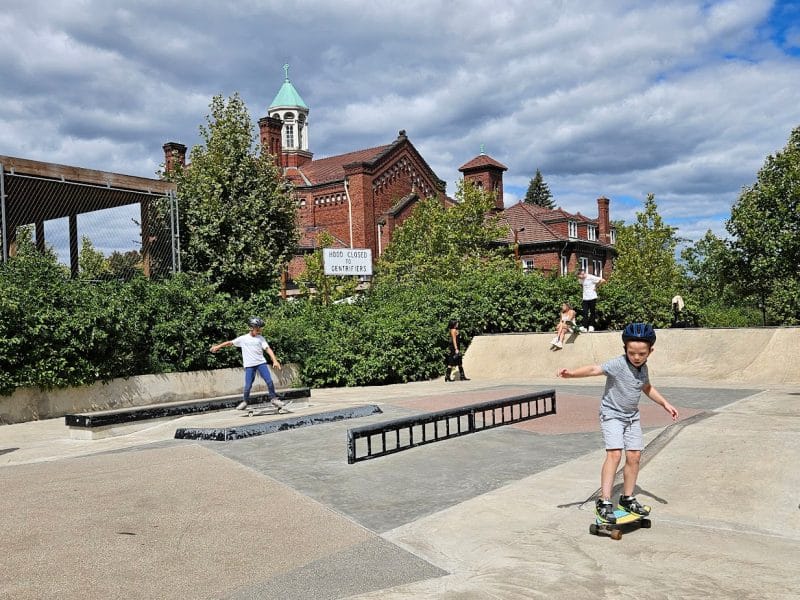

Then, on the southeast corner of Brainard and Second, a sign of resistance: “The universe will get you back.”

Put all the messages and the physical evidence together and they seem to point to one, big bad word repeated in cities from coast to coast: Gentrification. But if Detroit is indeed experiencing gentrification, which was first used in the 1960s to describe a working-class London neighborhood that was being radically altered by affluent new residents, is it qualitatively different in Detroit than it is in New York, Chicago or San Francisco — where desirable neighborhoods have become unaffordable to everyone but the super-rich?

Put all the messages and the physical evidence together and they seem to point to one, big bad word repeated in cities from coast to coast: Gentrification. But if Detroit is indeed experiencing gentrification, which was first used in the 1960s to describe a working-class London neighborhood that was being radically altered by affluent new residents, is it qualitatively different in Detroit than it is in New York, Chicago or San Francisco — where desirable neighborhoods have become unaffordable to everyone but the super-rich?

Does a rising tide raise all boats?

With the increase of development in the city, the discussion here is just beginning to open up, with threads on forums like Detroit Yes! joining in on the debate.

But the topic has been talked about for years in the country’s “global cities,” where neighborhoods that resemble Detroit’s West Village or North Corktown long ago were first “rediscovered” by artists, musicians and assorted subcultural dwellers. This “rediscovery” was then soon followed by serious money people investing in high-end French restaurants, trendy Italian shoe stores and expensive housing units. A 1999 article by Kari Lydersen explored the impact of gentrification on low-income and working class residents, and the unwitting connection that pioneering artists and bohemian pioneers share with the tide of investors that arrives once the neighborhood becomes “hot.”

Lydersen wrote of a “gentrification industry — made up of realtors, developers, mortgage lenders, and construction companies eager to capitalize in the area.”

Writing earlier this year in Planetizen, a newsletter dedicated to urban planning and development issues, John Norquist of the Congress of New Urbanism ruffled the feathers of some local officials by saying that gentrification was “a totally phony issue in Detroit.” Norquist also wrote: “the gentrification issue is best understood as nuanced with costs and benefits. It’s also better understood in local context, (and) it is genuinely a debatable issue in San Francisco or Manhattan.”

In his opinion piece, Norquist cited a study completed by Columbia University Urban Planning Professor Lance Freeman, “whose research showed that low-income residents were no more likely to move from gentrifying neighborhoods than those not experiencing gentrification. (Freeman) found that many people valued other benefits more than low rents such as lower crime and restored amenities like shopping or better access to jobs.”

An article about the study appeared last year in USA Today and has been a topic of discussion and on web forums, too, where the debate can rage on for pages:

The information battle tends to concentrate in neighborhoods that grew up quickly in the 1990s, a decade that saw sustained growth in several major U.S. cities. In Chicago, formerly distressed, gang-ridden sections of the near-Westside were redeveloped on a mass scale and renamed Bucktown, Wicker Park and Ukrainian Village. Other neighborhoods infused with new money became known as Andersonville, Wrigleyville and River North. Some critics who follow the bouncing ball of gentrification in Chicago say that it has produced one indisputable matter of fact: It has effectively distanced the city from the Midwestern “rust belt,” and helped elevate it to the status of the more coveted “global city.”

Local news, broken down neighborhood by new-newer-newest neighborhood, gets media attention in this online guide published by the Chicago Tribune.

The funky economics of Detroit

But what do a random selection of Detroiters think about gentrification? Outside Avalon Bakery — itself a working model of how a business with careful, sensitive plan can successfully integrate into a rapidly changing Midtown neighborhood — seemed the ideal spot to begin picking a few brains.

A white couple with a small child sat at a table sipping coffee and trying to interest their son in a bite from a slice of focaccia topped with olives, cheese and other vegetables; three young black women, all roughly of college age, came out of the bakery with bags of fresh baked goods; a black man, who appeared to be in his 40s, held a pair of drumsticks and tapped them on a newspaper box and other surfaces, simultaneously holding conversations with passersby as he played.

A white couple with a small child sat at a table sipping coffee and trying to interest their son in a bite from a slice of focaccia topped with olives, cheese and other vegetables; three young black women, all roughly of college age, came out of the bakery with bags of fresh baked goods; a black man, who appeared to be in his 40s, held a pair of drumsticks and tapped them on a newspaper box and other surfaces, simultaneously holding conversations with passersby as he played.

Mark Dancey, a painter and graphic designer who recently purchased a home in Southwest Detroit, was one of those passing by. When asked whether he thought gentrification was an issue here, Dancey said the city seems to have a built-in resistance to the kind of sweeping changes that took place in Chicago and New York.

“Some of it is plain economics: There is so much more money to go around in Chicago and New York,” Dancey said. “But Detroit is just so funky that it just wouldn’t appeal to the same kind of people who would invest in other cities. I don’t think the same people who want to live in a gated community would choose to live in Detroit. If you’re here, you want to be here because you like this kind of crazy experience.”

About a mile south, at a café inside the Guardian Building, Christopher Shumaker said he was buying a townhouse on Palmer because he liked having “a downtown life.”

“But I don’t really think of gentrification when I think about people moving into Detroit,” said Shumaker, 25, who has worked at temporary teaching jobs, for an insurance company and spins records at Bookies on Washington Boulevard to make ends meet. “I think a lot of us who are buying property are struggling to make it. I don’t have a sense it’s a bunch of rich people investing here and taking over the city.”

Shumaker said his biggest complaint so far is that other newcomers he meets don’t seem to know enough about Detroit’s basic geography, or are slow to make social connections.

“I joined the Detroit Athletic Club and I drink at Jumbo’s (a dive bar at Third and Selden),” said Shumaker, who attended University of Detroit Jesuit High School, and then spent four years at Santa Clara University in California. “I think people that are not so conventional are the ones who are attracted to Detroit, not what you’d think of as gentrifiers.”

“I joined the Detroit Athletic Club and I drink at Jumbo’s (a dive bar at Third and Selden),” said Shumaker, who attended University of Detroit Jesuit High School, and then spent four years at Santa Clara University in California. “I think people that are not so conventional are the ones who are attracted to Detroit, not what you’d think of as gentrifiers.”

But the discussion doesn’t begin or end here. Gentrification appears to be one of those topics that has no bottom, no ceiling. It poses many questions, but fewer answers. There are other voices to be heard: those who come and those who go, those who plan and those who develop, others who champion or resist. Those voices are out there, and will be heard as the Detroit version of this story continues.