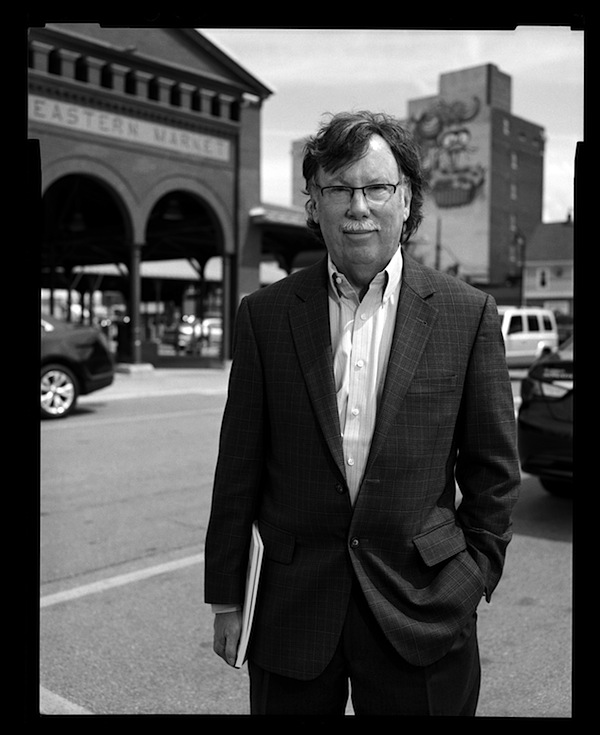

Talking revolution and reinvention with John Gallagher

John Gallagher's stories in the Detroit Free Press are required reading for all who are fascinated in the greater Detroit narrative: how a once dominant global industrial powerhouse retools itself for the future. Walter Wasacz brings the questions.

In his 2010 book, Reimagining Detroit: Opportunities for Redefining an American City, (Wayne State University Press), veteran Detroit journalist John Gallagher made observations about the changing city he covers for the Detroit Free Press.

In his new book, Revolution Detroit: Strategies for Urban Reinvention, Gallagher surveys governance, education and crime, economic models, and the repurposing of vacant urban land in the city. He looks at new methods that are working in other cities — Cleveland, Philadelphia in the U.S., Leipzig in Germany among them — that could be implemented here. And, in some cases (Eastern Market), already have.

Model D: Your new book Revolution Detroit: Strategies for Urban Reinvention is now out. This is your second book to take a deep dive into the city in less than three years. What fascinates you most about the Detroit story?

John Gallagher: Couple of things. The quality and number of imaginative beginnings people have made to revinvent the city in the face of its hardships. Detroit is not standing still. In some ways, of course, things are getting worse, but so many smart people are trying new and different things across so many fields that I’m encouraged.

And I’m also fascinated by the dramatic changes in persona that Detroit takes on over relatively short periods of time — from a modest Midwest city in 1900 to the world’s industrial giant in 1950 to the poster child for urban decay just 50 years later. I’m sure Detroit will be a different city in 2050, and we’re on our way now to figuring out what that city will be.

Finally, I would say that I’m fascinated by cities in general, and how so many cities of dramatically different personality are dealing with some of the common themes that Detroit struggles with.

Model D: You call Detroit one of the “most complex urban environments in the world,” also comparing it to other cities that have declined and then reinvented themselves. What makes it so complex, and how do you think it impacts its future?

John Gallagher: I think Detroit is now paying for its single-minded devotion to one industry in the 20th century. Autos carried Detroit to the top of the world by the mid-20th century, but if you look at the trajectory of automotive cities around the world, such as Turin or Flint, you get a sense that there is inevitably a downside to the rise up. The intensity of this experience created a heightened sense of social change and conflict, as well as some of the last century’s great cultural movements, from the American labor movement to Motown music, all of which played out against the backdrop of Detroit’s industrial rise. It’s a fascinating story.

Model D: One of the chapters, ‘New Ways to Govern Our Cities,’ suggests ways public-private partnerships have improved public safety in Cleveland and reinvigorated Eastern Market here. Talk a bit about how cities are adapting new models to survive and thrive.

John Gallagher: A lot of cities, including Detroit, are finding that municipal governments are no longer able to provide the services we normally think of as municipal in nature. That’s a consequence of moving the tax base to the suburbs over the past half-century without adjusting the municipal boundaries to account for this new reality.

So, half by design and half by happenstance, a lot of newer organizations are taking over distinct municipal functions, such as the University Circle Inc. group in Cleveland, which operates its own police force within city limits and performs urban planning and park maintenance and other functions. In Detroit, we see multiple examples of “spinning off” municipal functions to non-profit quasi-public bodies, including Cobo Center, the DIA, the Historical Museum, the Zoo, Eastern Market, Campus Martius, the RiverWalk.

All of those run better under their non-profit boards and professional management than they would under direct city control. The debate about this centers on whether such non-profit oversight boards are properly accountable to the voters and to elected officials, but nobody seems to deny that such professionally managed bodies do a better job than the city was or could do with these assets.

Model D: In the ‘Economics’ section of your book, you talk about how slow Detroit was to accept that the decades-long auto-dominant economy was never coming back – even as the industry began globalizing and disinvesting in the core of the city and relocating its facilities in the suburbs. The answer to this is surely complex. But what took so long for the city to come to grips? This trend began in the 1950s and lasted the balance of the 20th century, after all.

John Gallagher: I suppose the answer is that things were so good for so long that nobody wanted to believe it could ever end. In fact, I think there was a certainty that the good times — high profits, global dominance, high blue-collar wages — never would end, a certainty that was so strong that the opposite never even rose to conscious thought in peoples’ minds. It took the experience of defeat to finally wake people up.

Model D: You also talk about the importance of immigration, pointing out that Detroit was a city built by immigrants, and the blue economy. Talk about the value of each as factors for future growth.

John Gallagher: One of the interesting data points in the book is that Detroit’s immigrant population during its boom years in the early 20th century was much higher by percentage terms than it is now during our years of distress. That alone doesn’t necessarily imply correlation, but if you look at numerous other cities that have prospered, there does seem to be this connection between immigration, entrepreneurial vigor, a large and willing labor force, and a market need.

The blue ecomomy, meanwhile, is something that a lot of people are looking at as one possible economic future for Michigan. It’s not just that we have control over a lot of fresh water in Michigan — 40 percent of the Great Lakes, or more water by volume than Saudi Arabia has oil — but that we can create an economy based on cleaning, re-cycling, measuring, and otherwise using water.

The universities are all over this now, and the state economic leaders are starting to get behind this effort. It’s likely to produce a lot of small innovations and entrepreneurial efforts rather than one big bang. You’ll see things like companies producing new water meters and filters and recyclers and so forth.

Model D: Detroit is physically big, just shy of 140 sq. miles. It has a huge amount of vacant land. You write about urban agriculture, commercial farming and restoring the natural landscape (including daylighting Bloody Run and other creeks) as ways to reuse land creatively. Tell us why converting Detroit real estate from vacant to vibrant could be one of the future city’s greatest assets.

John Gallagher: Land has always been the basis of wealth. And our vacant land in Detroit, while overgrown with weeds and the site of dumped tires and so on, still has potential value. Many of the “green” uses now under discussion, like urban agriculture or reforestation, have economic implications. And “blue” infrastructure, such as artifical ponds and canals, can divert rainwater from our sewer system and save us millions of dollars in operating and capital costs each year So the “reimagining” of Detroit goes far behind the “feel good” aspect. It’s about dollars and cents.

Model D: Speaking of creative: you highlight artist-land acquisition activists Gina Reichert and Mitch Cope in the book. How are artists, and other creative, outside the box thinkers and doers, helping to reinvent Detroit?

John Gallagher: I think in a couple of ways. First, they inject a note of energy and color and sweat equity into their little corner of the city. Gina and Mitch are doing more than creating artwork in their neighborhood; they’re fixing up houses and bringing in new residents and tending to vacant lots and providing recreational opportunities. Second, artists operate within a broader economic infrastructure of galleries and museums and art supply stores and coffee shops and bars and clubs. Any great city has one or more lively arts districts, and many distressed districts in cities worldwide have begun to “come back” through artists moving in first.

Model D: You devote a chapter to lessons to be learned from Europe. What can a place like Manchester, England – which led the industrial revolution in the 1800s before years of decline and eventual reinvention in the late 20th century – teach us?

John Gallagher: We have to be careful here because the European legal and cultural assumptions are rather different than our own. The attitude of government in Germany, for example, is to support central cities as much as possible, with economic incentives, aid, legal changes, etc. That support helped the former East German city of Leipzig make a dramatic comeback after the fall of communism had cost the city 90 percent of its industry. One German planner told me that they try to make people feel really silly if they move out of town to the suburbs. In Europe, they believe in cities; in America, we believe in suburbs.

Having issued that caution, I still think cities like Manchester can teach us a lot. Much of the innovative work in Manchester was done by government really partnering with the private sector to advance economic change. In one high-tech digital hub that I visited, the board that ran it was comprised in the majority by private sector folks, even though the site was a government site. That led to much quicker and more nimble decision making — sort of like what we see in the non-profit entities in Detroit taking over municipal functions. In the book I recall how an editor told me before I left for Europe that it was easy for Europeans to help cities because they’re all socialists. But the thing that struck me about the comeback of cities like Manchester, Turin, and Leipzig was how entrepreneurial it all was.

Model D: Lastly, it seems you’ve just scratched the surface on the ‘reimagination and reinvention of Detroit’ narrative. There’s so much more to dig into. What’s next? Are you thinking about the next book?

John Gallagher: I agree that we’ve just scratched the surface here. The good news is that we have so many smart people working across so many fields to advance the cause. I’m sure it’ll produce some good results. And as for my next book, stay tuned…

There is a release party for John Gallagher’s Revolution Detroit: Strategies for Urban Reinvention this Wednesday, April 10, at D:hive, 1253 Woodward Ave., downtown Detroit. The event is 5:30 – 7:30 p.m. Food and soft drinks provided. Books will be available for purchase. There is a suggested $5 donation at the door.

Photo of John Gallagher ©copyright Gilles Perrin