Food pantry focuses on immigrants

Hamtramck’s Friendship House focuses on providing trauma-informed care for people in need of food assistance that reflects the diverse, ever-changing population of the city around them.

Metro Detroit has always been a city of migrants, from the European immigrants that came here in the mid-19th century to the Black community who arrived here from the American South during the Great Migration, this area has been shaped by people who began their lives in a place far away from Michigan.

Hamtramck, once a city closely identified with the Polish community, is now a true mélange of people from all over the world. It welcomes immigrants from Yemen, Bangladesh, Mauritantia, Sudan, and most recently refugees from the wars in Syria and Ukraine. “Our demographics represent what’s going on in the whole world,” says Cathy Maher, executive director of Detroit Friendship House, a nonprofit that serves new Americans in Hamtramck.

Primarily, Detroit Friendship House serves as a food pantry. Responding to the needs of people from so many different parts of the world, with very different foodways, is an important value for them and something they work hard to accomplish. There are always garbanzo beans and rice on the shelves, because they are applicable to the cuisines of multiple cultures.

Many pantry guests are Muslim and require halal proteins, which can be hard to source on a food pantry budget, so they have items such as lentils, peanut butter and tuna that can meet those standards, says Khurshida Hossain, a program director at Detroit Friendship House.

Friendship House is a client-choice pantry, which means pantry guests shop for what they prefer among the available choices, versus picking up a bag or box of pre-selected food that may or may not meet their needs. Eastern Michigan University helped Friendship House implement a program called SWAP (Serving Wellness at Pantries), which codes food choices into red (less nutritious), yellow (better) and green (best), that helps clients make healthier choices despite language barriers or lack of familiarity with some choices.

Friendship House is the only pantry in the greater Detroit area that has implemented the program. “Everyone understands what a traffic light looks like,” says Hossain. “It’s hard to inform clients of how to choose healthy options, and [the SWAP system] is true to our cultural offerings.”

SWAP is just one way Friendship House meets community members where they are. Most of the employees and volunteers are from Hamtramck, and many are bilingual. While that might seem like a coincidence, it’s actually one aspect of a trauma-informed approach to the food pantry that is key to what Friendship House does. They’ve received a gold-level certification from the USDA’s Nutrition Pantry Program, which evaluates pantries on how well they address factors that lead to food insecurity.

A large proportion of people who come for services are refugees from war or people seeking asylum from the threat of violence, and they carry the deep trauma of what they have experienced with them. Having someone who looks like them at the front desk, or someone who can speak their language, can help them feel more comfortable and safe when they seek help.

“We have to understand that being where they are, we can’t start with saying they have to build self-sufficiency,” Hossain says. “We started with our environment and giving them the dignity of choosing their own food.”

Another way that plays out is in their coaching program that helps people access services as they are ready. Rather than mimicking the governmental approach that has strict requirements, people seeking assistance to get settled in their new home can meet with a coach who will assess what they need and most importantly, what they are ready for, and connect them with those services. A follow-up interview is scheduled to ensure clients were able to access what they needed and to identify future needs.

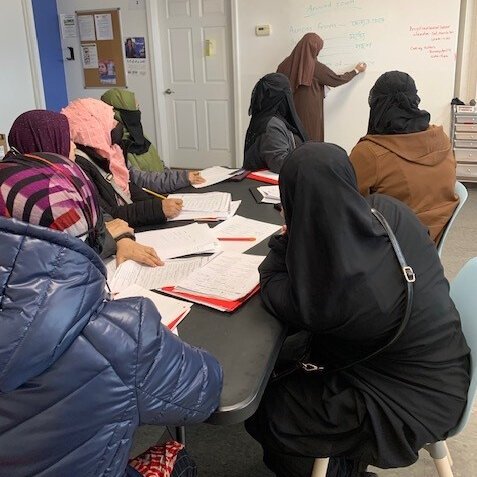

For example, many women struggle to access language classes because they are at night, and they don’t have childcare. Co-ed classes are also frowned upon in many cultures. Friendship House offers classes that are only for women, and during school hours, so that women with children are able to learn English while their children are at school.

“What we found is women in our community are at more of a disadvantage,” Hossain said. “With me living in the community, I understand the cultural nuance.”

Maher is retiring from Friendship House, but in the future she would like to see the non-food programs grow and expand.

“Everyone knows it takes more than food to end poverty, and we’re building programming that helps break down the barriers that keep people stuck in poverty,” she says.

This story is part of our Nonprofit Journal Project, an initiative focused on nonprofit leaders and programs across Metro Detroit. This series is made possible with the generous support of our partners, the Ralph C. Wilson Jr. Foundation, Michigan Nonprofit Association and Co.act Detroit.