Fields of Dreams

If

the Tiger Stadium walls come tumbling down as planned, Corktown

residents and business owners say other walls will go up. The stadium’s

former parking lots are declared redevelopment ready.

Plans to redevelop Tiger Stadium mean more than building a few

structures on that block. Corktown leaders believe it will drive

development in the old Irish enclave and clear out another reminder of

the stadium’s busier days: old parking lots.

The city, which

owns Tiger Stadium, has proposed plans to tear down most of the stadium

while preserving the field as a park. Mixed-use buildings, lofts and

storefronts will then be built around the field. Parking lots aren’t

part of the plan.

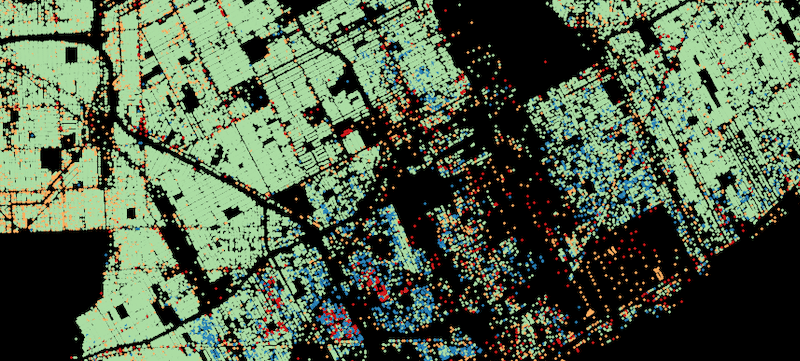

Those old lots of asphalt, gravel and grass –

Those old lots of asphalt, gravel and grass –

often covered with garbage, weeds or cracked asphalt – make up about 70

percent of the greater Corktown area and have sat empty since the

Tigers left seven years ago. But these fields of dreams are filled with

potential.

R. Scott Martin Jr., the Greater Corktown Development

Corporation’s executive director, says the parking lot owners haven’t

developed the spaces in hopes another single-use tenant, such as a

sports team, moves into the old stadium. That would allow them to once

again collect bundles of cash in parking fees while paying low taxes on

property requiring little upkeep. “You can’t blame them,” says Martin,

a Corktown resident. “They’re business people, too.”

If the

stadium went multi-use, however, the development could spill over.

“Then these parking lots will naturally become available for

development,” Martin says. “At least at that point, nobody has an

argument for hanging onto them.”

Filling in

Development in Corktown is taking place on small and large scales now.

The

Grinnell Place Lofts project is progressing. Developers are building 34

lofts in the old Grinnell Brothers Piano Warehouse, located on Brooklyn

Street just north of Michigan Avenue. Half of those units, priced

between $163,000 and $390,000, are sold.

Diane Meidell, the

Diane Meidell, the

project’s operations manager, said the developers want to build in

Corktown again. She believes the Tiger Stadium plan plays to the

neighborhood’s strengths, history and location by preserving the

historic field and opening up more land for development near downtown.

“It’s

such a great neighborhood,” Meidell says. “What a perfect set up to

have that (downtown) urban lifestyle and still live in a neighborhood.”

And

not everyone is waiting on the stadium to take advantage of Corktown’s

assets or develop the lots. Jason Nardoni recently brought an old

Corktown worker’s cottage, at least 125 years old, back from the brink

of destruction. Most of his neighbors marked the house, a burnt-out

shell, as beyond saving when he bought it in 2004.

Nardoni,

31, and some friends saw it differently. They gutted it, rebuilt it,

gave it modern amenities and added a garage while maintaining its

Victorian craftsmanship.

Even though the cottage looks much

like it did when it was first built, 85 percent of the house is new.

The $100,000-plus investment turned Nardoni’s 1,200-square-foot,

two-bedroom, one-bath home into a head turner on his block.

During

During

the day, the information security specialist walks to his job downtown.

At night he watches the city’s skyscrapers from his backyard.

The

cottage came with an adjacent lot that where a similar house once

stood. Over time it became a parking lot, but no more. Nardoni plans to

build another house there in the near future to help complete his

block. He’s more interested in density than a bigger yard. “If every

other house was knocked down so everybody can have a bigger yard then

that would take away from Corktown’s charm,” Nardoni says.

And

less density would reduce the number of eyes on the street. Corktown’s

Martin explains that more houses and businesses mean more potential

eyes watching, making people feel safer.

Jana Cephas, a

research fellow at the University of Detroit Mercy specializing in

urban design, agrees. The former Corktown resident says parking lots

detract from a neighborhood’s urban feel. “Whether it’s a parking lot

or a vacant lot, really there isn’t a sense of safety because people

aren’t there,” he says. “It feels less safe and less like a community.

It’s actually a huge waste of land.”

Moving forward

If

the Tiger Stadium mixed-use plan goes forward and the parking lot

owners still don’t develop their land, Martin plans to push for

land-value taxing in Corktown.

“It’s basically a policy where

“It’s basically a policy where

buildings are taxed much less and surface lots are taxed higher,” he

says. Martin hopes it won’t have to come to that because these people

are still neighbors and local business owners.

Ray Formosa is one of

them. Formosa, born and raised in Corktown, owns a few parking lots in

the neighborhood, as well as Brooks Lumber on Trumbull Avenue.

He

wants to see something done with Tiger Stadium and is open to razing it

if it helps the neighborhood. He is even open to developing his parking

lots. But for now, he’s waiting. “Yeah, it’s something to look forward

to, but it becomes believable when it happens,” he says.

Martin

says it will happen, even though critics and naysayers insist

otherwise. He says an auction of stadium memorabilia will happen this

fall, followed by demolition of most of the structure beginning late

fall. The field, dugouts and some seats will be preserved. Then, late

spring or summer 2007 will see construction start on the mixed-use

buildings around the field. It all should be wrapped up in about three

years.

The plan is moving forward, he says, although he knows

some won’t believe it “until the jaws start tearing into the stadium.”

And those empty lots will become history, too.

Photos:

Tiger Stadium

Scott Martin

Grinnel Place

Jason Nardoni’s Rehabbed Cotage

Ray Formosa of Brooks Lumber

All Photographs Copyright Dave Krieger