What is ‘true’ community engagement? Exploring the trendiest term in Detroit today

To better understand what true community engagement is, we spoke with Detroit engagement professionals to learn their processes and find out how the city — developers, local government, and even community organizations — can do better by Detroiters.

When Dan Pitera gets really excited about something, he starts drawing.

That’s what he did when describing PlayHouse, a design for a performance space that utilized part of an abandoned house. Detroit Collaborative Design Center (DCDC), a nonprofit University of Detroit-Mercy design firm of which Pitera is the executive director, made the renderings in 2010 for a community group that wanted to productively use some vacant parcels.

But as much as he illustrated the way the house would become a shell and open up to the adjacent empty lots, he also illustrated the community engagement process. Every project undertaken by DCDC begins with an exchange of ideas between designers and residents — the community uses its expertise of the neighborhood to tell DCDC what it wants, and DCDC brings its expertise in design to bring them to life. Then there’s feedback on those designs, until, many iterations later, DCDC is showing residents blueprints.

“If you were designing a library, you wouldn’t think twice about talking to a librarian,” Pitera says. “Why should we not be doing the same thing with people down the street? They’re experts on their neighborhood. The arrogance that we are experts and others are benefiting from our expertise is missing the point.”

But too often, according to Pitera, designers start by asking for feedback on already made renderings, skipping the exchange stage altogether. “People often say, ‘I can’t show the community my plans because they get upset,'” he says. “Well, only if it comes before ideas are actually shared.”

Despite the fact that “community engagement” is one of the trendiest terms in Detroit today, these issues come up with surprising frequency. Developers tout how many meetings they held. The city of Detroit cites the number of people it engaged. Projects define themselves as “resident-led.” (This publication is not immune from using that language.)

And yet, many developments, plans, and projects continue to alienate and upset Detroiters. For as much as business and civic leaders promote their engagement efforts, something essential is still missing from the process.

To better understand what true community engagement is, we spoke with Detroit engagement professionals to learn their processes and find out how the city — developers, local government, and even community organizations — can do better by Detroiters.

Empowered decision-making

The first problem might be one of definition. On a basic level, community engagement is having residents participate in the process of creating a project, plan, or development.

But a variety of events and outreach efforts fall under the header of “community engagement.” And not all efforts are equal.

The International Association for Public Participation describes a spectrum of activities that can be classified as community engagement. The most basic form involves simply informing the public of what you intend to do. From there, the project lead could consult, involve, or collaborate with residents. And at the highest-engagement level, they could empower — actually give the community the ability to shape the project.

That’s what the Eastside Community Network (ECN) did during the creation of the Lower Eastside Action Plan (LEAP). After the devastation of the housing crisis, much of Detroit east of Mt. Elliot Street and south of I-94 was left vacant. In 2009, ECN, a coalition of community groups in the area, began identifying productive uses for that vacant land. It sought professional partners in academia, planning, funding, and design.

But most importantly, it gave residents the power to shape the plan.

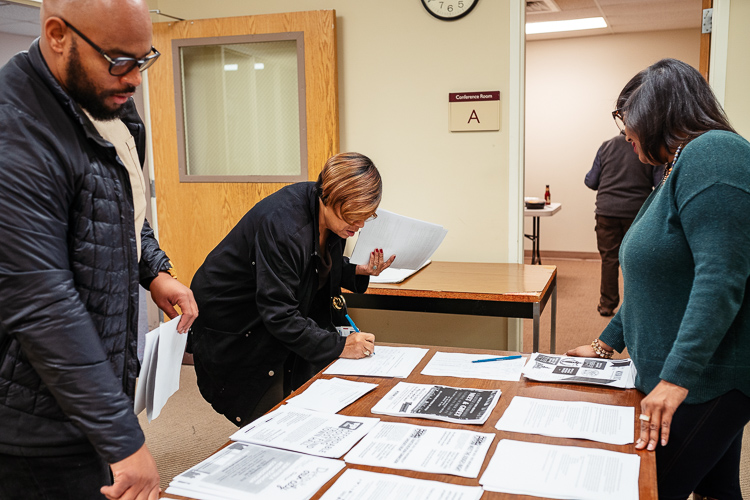

Seven community development organizations in every LEAP district helped get residents involved. Then ECN hosted large community meetings with up to 200 residents who listened to technical expertise and recommendations from professionals, and voted to adopt uses and typology for every parcel in the area.

“One of the amazing things about LEAP is residents own it,” says Orlando Bailey, director of community partnerships for ECN. “Why? Because they made decisions every step of the way.”

The process was lead by a steering committee chaired by residents who would give final approval. According to Bailey, “They almost always confirmed residents choices.”

LEAP I and II were published in 2012. When ECN felt it necessary to update to the plan in 2017 to address changing conditions in the city, it had no problem organizing residents because the infrastructure never disbanded. Both the steering committee and a blight task force still meet regularly, and the original planning process helped create a stable of community organizers.

“Everyone is still invested in what we created in 2012,” Bailey says.

LEAP was the pilot for a strategic framework developed by the Community Development Advocates of Detroit (CDAD), a collection of community residents and leaders who share knowledge, advocate for policy, and development engagement practices.

Since LEAP, the framework has been utilized in other plans across the city, including Restore Northeast Detroit, Cody Rouge, and Chadsey-Condon.

“We feel very confident that what we get out of those efforts are community visions that are the actual will of residents, not just community leaders or other stakeholders,” says Aaron Goodman community engagement manager for CDAD.

“Community engagement is work”

In his role, Goodman has seen every variety of engaging residents. A lot of times, it’s done poorly or insincerely. The biggest problem he sees is that it’s not given the space, time, or resources it needs.

“Community engagement is work,” he says. “It’s not just a one-time process. It’s about actually nurturing and holding relationships on a long-term basis.”

And then, according to Goodman, projects which do sincerely want to engage residents often fail to ask basic questions. “Do you have childcare at the meetings? If you’re holding it at 6 p.m., do you have food? How are you reaching out to people? Are you just relying on email or are you going door to door? Are you connected to more informal networks in a neighborhood so you can actually get in front of and engage with folks who aren’t able to come to meetings on a weeknight?”

Good facilitation is another overlooked and essential feature to a productive meeting. That often involves some translation of professional jargon, a lot of listening, and working through difficult subjects.

At a talk hosted by the Urban Consulate on June 11 this year at DCDC, author and placemaker Jay Pitter presented her “10 Placemaking Principles.” Number one on that list is “design is not neutral.”

“Design comes from a very particular cultural and gendered place,” Pitter said. “We see it through street names and monuments. Sometimes it’s invisible like paved-over burial grounds. A lot of vulnerable communities have been designed over and designed out of cities. It’s important to be cognizant of that history if we are to design and co-create inclusive cities of future.”

Bailey thinks the city as a whole is working too fast and not giving Detroiters time to acclimate to the changes. That can result in flare-ups.

“You cannot go into a neighborhood and plan to engage people around big, new, shiny things when trauma exists,” Bailey says. “Homes that have been demolished, schools closed, neighborhood institutions closed. When people get an opportunity to express themselves, you have to find way to facilitate that in a productive way.”

In short, there’s no simple way to do community engagement. It takes patience, empathy, resources, and a commitment to putting others ahead of yourself. But in the end, it’s worth it.

“If you care about a city that’s ‘for all,’ that’s inclusive, that develops in a way that actually benefits long-time Detroiters and people most marginalized, then they have to be at the table,” Goodman says. “If you care about that, then you have to do it and take it seriously.”

This article is part of our Equitable Development series, in partnership with Doing Development Differently in Metro Detroit, where we explore issues and stories on growing Detroit in a way that allows people from all races, classes, and abilities to participate and benefit. Read more articles in the series here.

Support for this series is provided by the Knight Foundation, Knight Fund at the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Photos, except where mentioned, by Nick Hagen.