A look at how climate change will affect Detroit neighborhoods

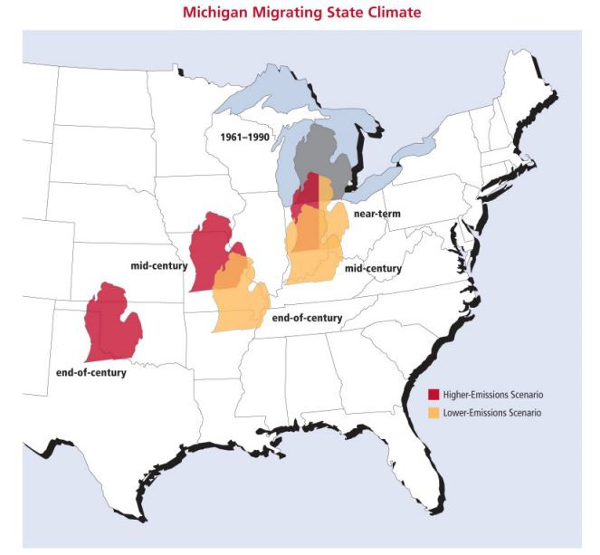

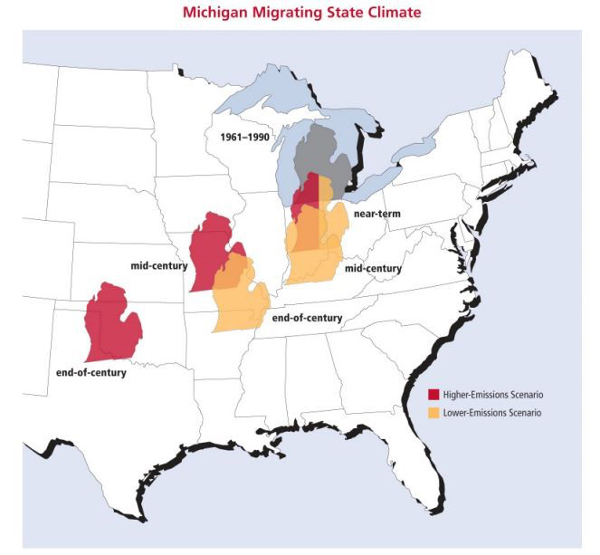

By the end of the century, Detroit's climate could be more like that of southern Missouri today. Here's a look at the challenges climate change poses to Detroit and the neighborhoods most at risk.

The specter of climate change is looming over the Great Lakes and Michigan.

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, Michigan can expect much hotter summers by the end of the century. In 2100, scientists estimate that temperatures will exceed 90 degrees Fahrenheit for 65 days of the year, getting over 100 degrees for 23 of those. If the business of fossil fuel-related emissions continues as usual, summers in Detroit will feel more like Missouri than Michigan.

Extreme heat poses a greater risk than mere discomfort; it raises the risk of heat stroke to the very old and very young and worsens air quality, producing more smog and exacerbating conditions such as emphysema and asthma.

In addition to hotter summers, Michigan’s changing climate will also experience increases in rainfall. While total rainfall predictions are unclear, we can be sure that when the rains come, they will come all at once. In the fall and spring, when the ground is already wet and unable to hold more water, rainfall could increase by 25 percent by the end of the century. This will overwhelm Detroit’s aging stormwater systems, flooding basements and streets and leading to sewage overflows into the Detroit River and Lake Erie. Storms like the one that caused flooding across the region in August 2014 may become commonplace and will exacerbate problems that led to Toledo’s loss of drinking water in the summer of 2014.

Climate is measured at comparatively massive geographical scales, so making predictions at the city-scale about how climate change will affect future weather and seasonal patterns is difficult. There is no crystal ball. We can know, however, “who” and “where” will be most vulnerable. With an understanding of the geography of climate change, Detroit can develop intelligent adaptations based on big data and justice.

Adaptation and gentrification

With development in Detroit accelerating, it is important that Detroit leaders take a hard look at where the city will be most vulnerable to climate change and target resources to those neighborhoods. Detroit, just catching its breath from bankruptcy, cannot afford to build climate resilience in the wrong neighborhoods.

Kimberly Hill Knott, policy director for Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, worries that climate change will “exacerbate public health challenges and inequality in hot spots around the city.”

“Green infrastructure and other developments to adapt to climate change must be built based on who is most vulnerable,” she says.

While greater downtown is primed for development and greening, that area’s social and physical characteristics make it relatively resilient to climate change. Green infrastructure cannot just be a method for developers to raise property values. It is a vital component of building a stronger and more equal city. Targeting of climate adaptation techniques must be based on solid foundation of physical and social vulnerability.

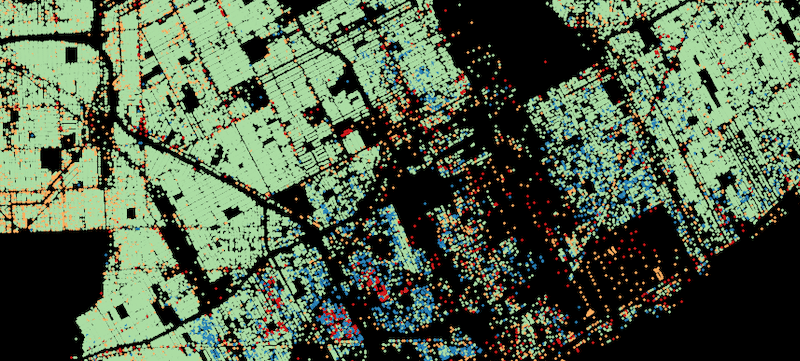

Building the foundation of a climate-resilient city requires planning that is anchored in big data. Paul Edwards, author of the recent book “A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming,“ says that Detroit can make decisions based on information and data “by making better use of what is there.”

“Police, fire, and utility workers already keep logs,” says Edwards.

By digitizing this data and deliberately planning a strategy for useful data collection, the development of the information-centric city “doesn’t have to be terribly expensive.” An ongoing strategy of collecting data about infrastructure conditions, paired with existing data sets on climate, soils, and human geography, can be used to develop “big data” strategies for managing the urban environment.

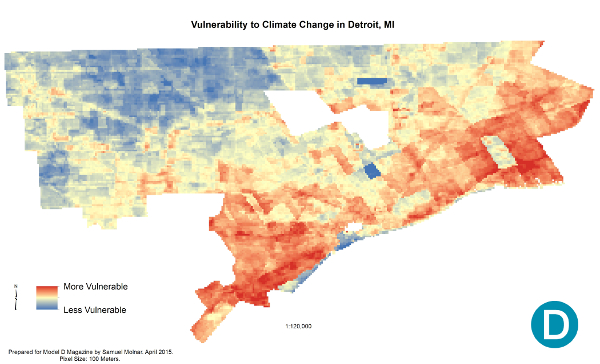

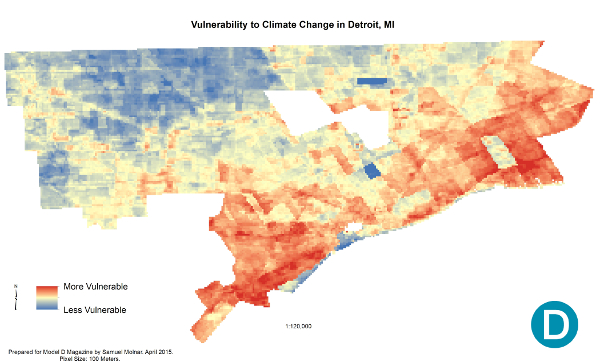

With the limited data currently available, Model D has created a map of where Detroit is most vulnerable to climate change. It can point in the direction of where Detroit should begin preparations for the impacts of climate change.

Southwest Detroit: An All Too Common Story

This map, produced in winter 2015, shows areas which are most vulnerable to climate change in Detroit. It uses a mixture of physical indicators such as temperature, housing stock, and flooding risk, along with social indicators like age, asthma rates, and neighborhood stability, to create an index of climate change vulnerability. The most vulnerable areas are shown in red, while the least vulnerable are shown in blue.

This analysis compares the city of Detroit in relative scale to itself, so while all of Detroit is vulnerable to climate change, some areas are more vulnerable than others. A lack of good available data on flooding probably downplays the vulnerability of neighborhoods that sit in and around the Rogue River, which have been known to flood after even moderate storms. The neighborhoods most vulnerable to climate change are clustered in Southwest Detroit.

Presented with the findings, Antonio Cosme, a community organizer in Southwest Detroit and a founder of The Raiz Up collective, was not surprised.

“Environmentally, we [Southwest] are the most vulnerable. With tar sands, the freeways, we have highest asthma rates,” he says.

Southwest Detroit is a prime candidate for building infrastructure that can harden the city’s infrastructure and residents to climate change impacts. It remains to be seen, however, if green infrastructure will be built to address real needs, or if it will come part and parcel with a gentrification process.

Cosme insists that climate change adaptation and green infrastructure construction must be rooted in the public good and welfare.

“The Hantz Farms route is not the way to do it,” he says. “Hantz’s company is taking down old trees to plant new small trees. Rather than selling land on the cheap to large landowners, the city should be encouraging and protecting community farming. Planting native species would be an excellent solution, they help hold the ground together and absorb toxins.”

By starting with climate resilience rather than business development, Detroit can build the foundation of a green economy.

“The proper response to the brain drain in Michigan is walkable, clean, attractive, climate-resilient cities,” says Kimberly Hill Knott. “These will attract money and residents to the city.”

Manage the unavoidable, avoid the unimaginable

Nestled firmly in the southwest corner of the city is a driver of climate change — the Marathon refinery and the petcoke piles of recent memory. Pound for pound, tar sands and their byproduct, petcoke, are worse for our planet than classic crude oil. This type of oil mining, which is practiced in Alberta, Canada, and refining, which is practiced in Southwest Detroit, has been called a “carbon bomb” by renowned NASA climate scientist James Hansen.

While we must prepare for climate change now in our cities by adapting our infrastructure and our planning, we can’t lose sight of the higher goal. We have to bring climate change to a halt in this generation. The only way to do that is to get off fossil fuels.

On April 14, at an event hosted by The Raiz Up, over 100 people gathered at the Cass Corridor Commons to commit to ending the mining and burning of tar sands oil.

“Detroit is in a moment that is reflecting a greater moment that the world is facing in terms of climate change,” says Cosme.

We have the opportunity to build a low-carbon and climate-resilient city right here in the heart of the Great Lakes. It’s high time for Detroit to seize the moment.

—

Samuel Molnar is a graduate student in the School of Natural Resources and Environment at the University of Michigan. He works with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration to study the effects of climate change on cities in the Great Lakes Basin. He can be reached at SamAlbin@umich.edu.