Black Bottom Archives celebrates 10 years

“Part of our next 10 years is building the next generation of black archivists and storytellers.”

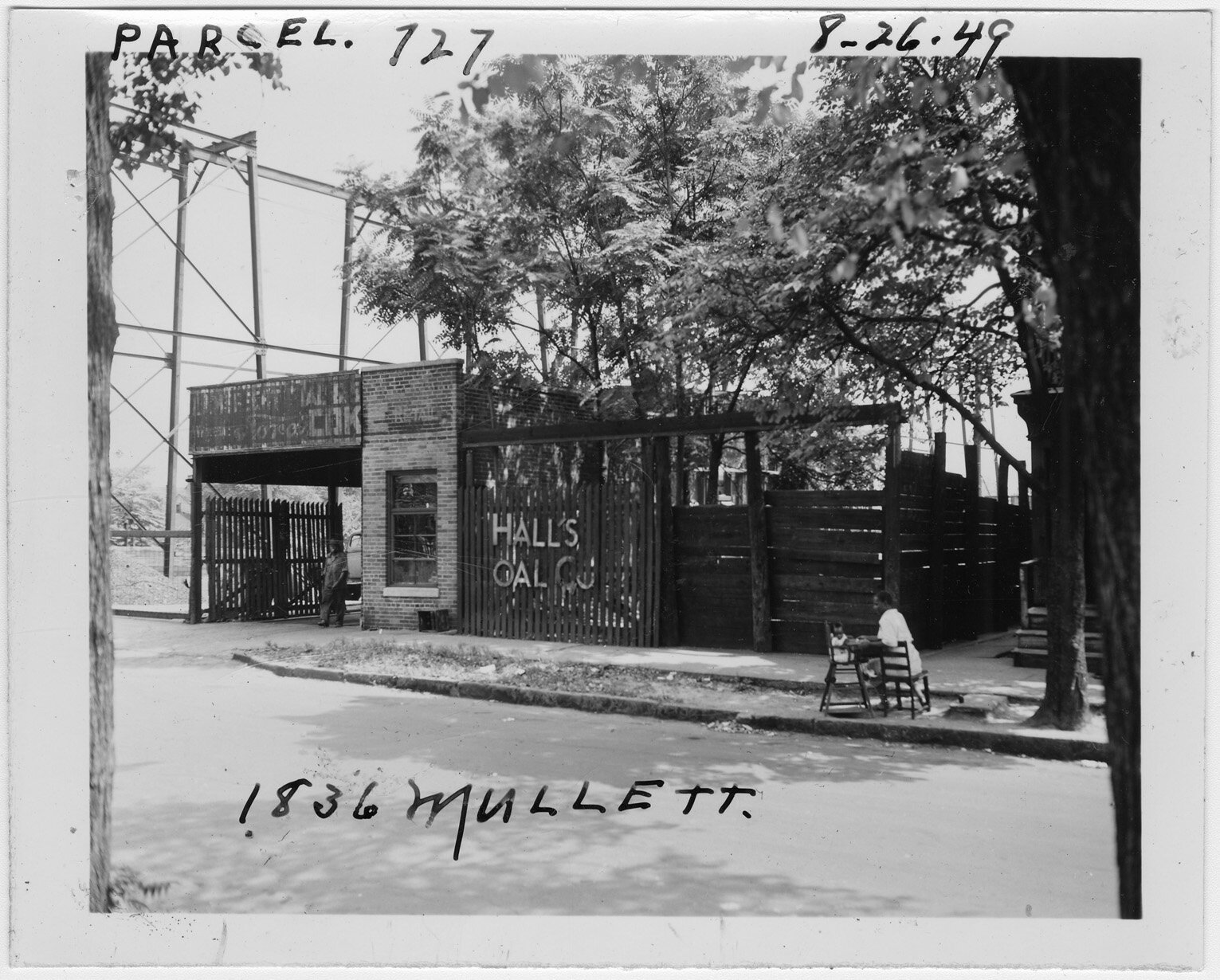

For over 3 decades Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were full of thriving Black enclaves, churches and jook joints pumping jazz into the streets.

Located near Detroit’s east side bordered by Gratiot Avenue, Brush Street, and the Detroit River, it was demolished by the city of Detroit via an urban renewal project in the late 1950s through early 1960s. It was then replaced with the Lafayette Park residential district and the (now much-contested) Interstate 375.

At its peak, there were an estimated 130,000 of residents living in Black Bottom and Paradise Valley with an estimated 300 African American owned businesses according to a report sent to Detroit City Council on September 20, 2023 from David Whitaker, the director of the Legislative Policy Division.

The report details 10,000 structures demolished and 43,000 residents displaced with most receiving little to no relocation help. The removal of Black neighborhoods and Black-owned businesses was devastating and the memories of the communal richness of the people and the area seem more lost to history with each year that passes.

Enter the Black Bottom Archives (BBA), a community-driven media platform started by P.G. Watkins and Camille Johnson in 2015. The organization is dedicated to centering and amplifying the voices, experiences, and perspectives of Black Detroiters through digital storytelling, journalism, art, and community organizing with a focus on preserving local Black history & archiving our present.

“They wanted to create a platform in response to the present day gentrification and displacement they were witnessing and the media that was associated with that that was erasing a lot of the Black stories from what was actually happening in Detroit,” says Marcia Black, Co-Executive Director of Archives and Education. “They wanted to make a digital publication that would center black Detroiters, and so it started off as a Tumblr page, then a website.”

“They were charged and really excited to activate the community around education about the history of what was going on in the neighborhood,” adds Lex Draper Garcia Bey, Co-Executive Director of Community Engagement and Programs.

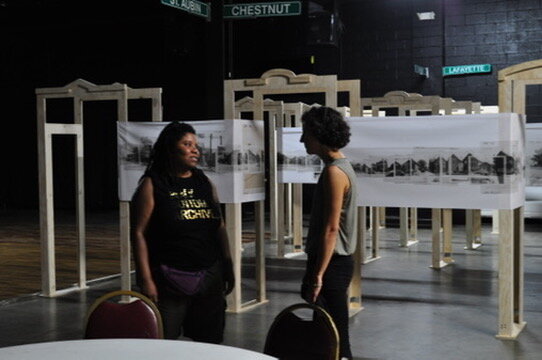

Over the years they’ve collected photographs, written essays, art, and and recorded oral histories from descendants of black Detroiters who once resided in those neighborhoods. This year marks their 10th anniversary and to commemorate this milestone, BBA invites the community to the launch of its exhibit, “10 Years Back, 10 Years Forward,” opening on February 8 at the Detroit Historical Museum.

This dynamic exhibit will feature zines, oral histories, podcasts, photos, and interactive displays that showcase BBA’s journey from a grassroots Tumblr page to a vital community archive. Visitors will have the opportunity to honor the past, engage with the present, and imagine the future of Black Detroit through the lens of BBA’s transformative work.

“We are interviewing residents and descendants of residents, people who lived, worked, and played in the area[…]through these stories we get to watch Black Bottom come alive,” Garcia Bey says.

“I think a part of the resonance name of Black Bottom is that the narrative of erasure isn’t something that’s specific to Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, but it’s an ongoing theme that we can see present,” Black says.

The eradication and insensitive modernization of black communities is not unique to Detroit. Cities like Oakland, Baltimore, and Rochester, N.Y., also have historically Black neighborhoods that have been discarded. Black says she’s communicated with Black residents in Kentucky all the way to South Africa who are also examining ways to archive the voices of Black communities gentrification has left behind.

“Just understanding what’s at risk if we don’t play a role in preserving our communities’ histories. Like why these stories were erased and easily accessible to us is not our fault but it is our responsibility to make sure that it isn’t an ongoing problem for future generations,” Black says.

Last year the City of Detroit kicked off its I-375 Reconnecting Communities Project, a plan to replace I-375 with a surface-level boulevard. The plan allows Detroit the opportunity to better connect neighborhoods to downtown and also right an historical wrong. While the overall project is much needed and commendable, efforts by the city of Detroit to preserve and incorporate Black Bottom and Paradise Valley’s rich legacy into its current narratives has been minimal at best.

“It’s not surprising that it’s not supported or that the efforts aren’t there as it should be because the decision was made in the beginning for it to be torn down. Because if that was the case and they were vested in it, we wouldn’t be there doing this,” Garcia Bey says.

Because Black Detroiters have a history of battling redlining, poverty, income disparities, and eviction; prioritizing holding onto old pictures, documents, and passing down stories has not been possible for all. BBA has tried to mitigate that by making sure all their programs and incentives are intergenerational, simultaneously extending an olive branch to former Black Bottom residents while engaging young adults as a way to teach the importance of preserving their history.

“The reason why Black history hasn’t been invested in over the years, I think it looks differently. I think with Detroit it’s been a theme of economic instability[…].It’s a privilege to be able to tell your story. It’s something that privileged folks have learned how to do consistently,” Black says.

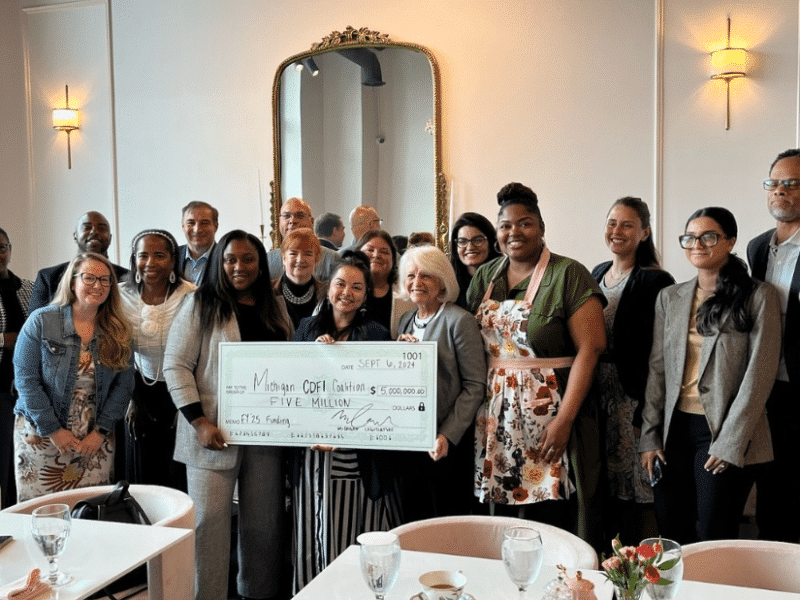

BBA received a $350,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation in 2024, expanded their staff, and have started an incentivized fellowship program where they’ll take about a half-dozen Black Detroiters and work with them in achieving their history.

“Part of our next 10 years is building the next generation of black archivists and storytellers,” Garcia Bey says.

“It’s about sustainability, money — how we can be self-sufficient and not allow our work be determined by people in power funding interests and current trends and what aren’t current trends,” Black adds.

Overall, BBA wants to continue to grow its reach, its impact to the city, and ultimately not let the voices of old Detroit get drowned out by the narratives of what people want a new Detroit to be.

“This aspect of being seen as being a black person. Being documented, recognized for your contributions whether or not you’re a millionaire or a politician. Like the fact that someone still sees you as a person worth remembering and as a person that has something to offer to help us tell this story,” says Black