Do Ann Arbor and Detroit need stronger ties?

Though they're a mere 45-minute drive apart, Detroiters and Ann Arborites often talk about each other's cities as if there's a massive gulf between them. We examine connections between the two cities and how they can be leveraged to greater effect.

Growing up in Detroit, Feodies Shipp III remembers that many of his neighbors regarded Ann Arbor as a sort of “mythical place.”

“It might as well be 200 miles away,” says Shipp, who now lives in Ypsilanti and is the acting director of the University of Michigan (U-M) Detroit Center. “It just seems so distant and remote.”

Similarly, when he was growing up in Ann Arbor, Tyson Gersh says he thought Detroit Metro Airport was the city of Detroit.

“I remember the first time I really came [to Detroit], I was in disbelief that there were skyscrapers,” says Gersh, who now lives in Detroit, where he is the president and cofounder of the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative. “I just didn’t realize.”

The language that comes up when Detroiters and Ann Arborites talk about each other’s cities is often striking, communicating some sort of massive gulf between two communities that are a mere 45-minute drive apart.

More uncommon are perspectives like that of Washtenaw County commissioner and Ann Arbor resident Conan Smith. Smith’s grandfather is Albert Wheeler, Ann Arbor’s first black mayor, and he grew up during George Goodman and Coleman Young’s terms as mayors of Ypsilanti and Detroit, respectively. Smith says his upbringing amongst this group of African-American politicians gave him a sense of a regional connection between Detroit and Ann Arbor that’s “rooted in those cities’ capacity to advance social justice.

Smith says connections between the cities exist, both economically and socially, but “for some reason we haven’t leveraged them to create the kind of affinity that would help both our communities to be more successful.”

In partnership with Concentrate, our sister publication in Ann Arbor, Model D took a look at some of those connections and how the two cities could better engage with each other to take advantage of them.

What are we missing out on?

Local stakeholders agree that there are major untapped benefits for both Detroit and Ann Arbor in better taking advantage of the talent stream coming out of U-M. In 2013, 40 percent of U-M’s alumni lived outside the state, and the state of Michigan continues to have one of the lowest net migration rates in the nation for young college-educated people.

Ned Staebler says that’s partly because Ann Arbor isn’t a big enough city to support the employment and cultural needs of new U-M grads, and the much bigger city to the east often isn’t even on their radar. Staebler, who grew up in Detroit and now lives in Ann Arbor, is Wayne State University’s VP of economic development and president & CEO of TechTown Detroit.

“We need to build the pipeline so the folks from Ann Arbor end up in the city of Detroit instead of in Chicago or Boston or San Francisco,” he says.

Smith echoes that sentiment, noting that encouraging more U-M grads to consider Detroit would help to buoy both cities and the state as a whole. Furthermore, he notes that Ann Arbor has the benefit of getting “the best and brightest” from the university to work on “even the smallest problems”—an opportunity Detroit could also tap into were the communities better connected.

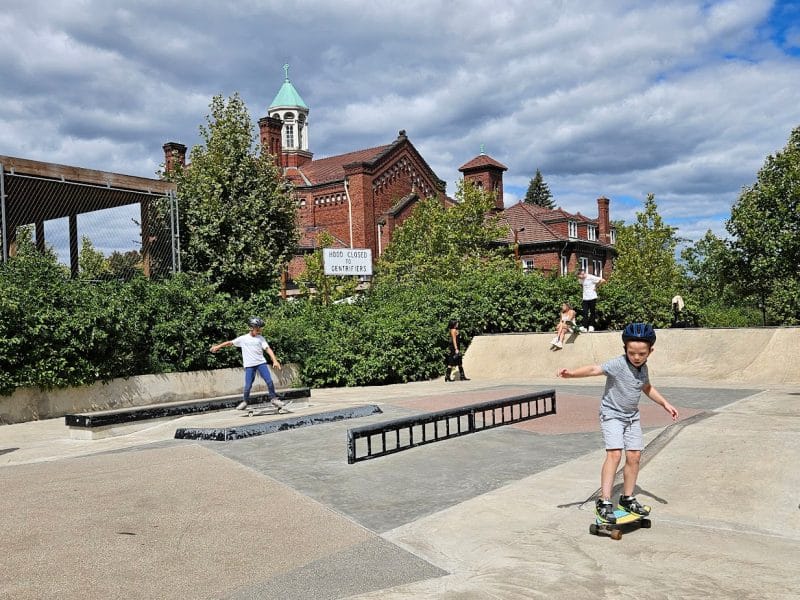

Gersh criticizes an “in-group/out-group” mentality among Detroiters that can create a disdainful attitude towards Ann Arbor. He thinks that’s harmful not just because Detroit could take some lessons from Ann Arbor’s successes, like its cultivation of green space, but also from some of the ways in which Ann Arbor has ostensibly stumbled. Gersh laments the way numerous locally-owned businesses in Ann Arbor have given way to national chains since his childhood years, and suggests that Detroit should be careful not to follow the same path as its revitalization continues.

“I think Ann Arbor is sort of rolling out the red carpet a little too much for market forces and economic trends,” Gersh says. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m really happy that there is a corporate presence there. But I think things that make cities special are often local businesses and things that may not be directly profitable … and I think for that reason [Detroit] may do well to find a way to subsidize some of the special things that make a space a space.”

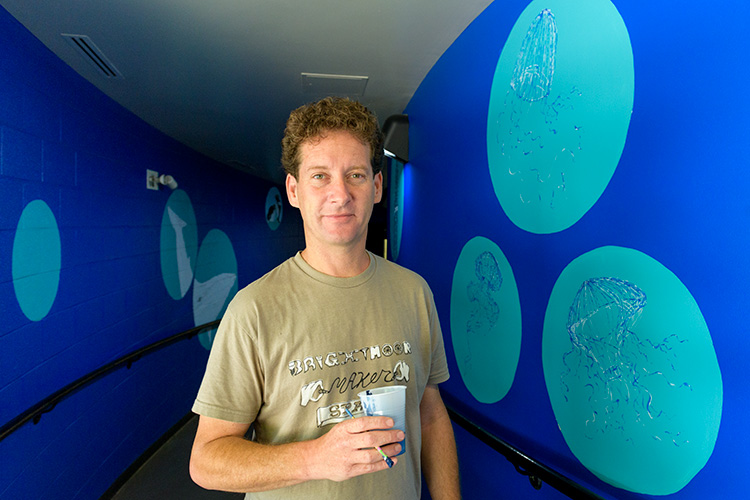

Gersh notes that while both communities are politically liberal, there’s a “wider degree of political opinions” in Detroit compared to Ann Arbor’s more “homogenized” political culture. U-M art professor Nick Tobier, who lives in Ann Arbor and has worked with students in Detroit’s Brightmoor neighborhood for the past nine years, similarly suggests that Ann Arborites generally lack exposure to true cultural diversity.

“I think that encounter with racial and ethnic and economic difference is something that we’re missing in Ann Arbor,” Tobier says.

“It shouldn’t be a colonial project”

Over the past decade, Ann Arborites have displayed increased willingness to visit Detroit and engage with certain cultural attractions as the city’s revitalization narrative has played out.

“People thought [Detroit] was this hellhole, for lack of a better word, of crime, blight, and problems,” Shipp says. “With all the investment, reinvestment, and development going on in the city, perceptions are changing. People are excited about Detroit.”

But that change has brought certain problems of its own.

“I think that some Detroiters would say some people in Ann Arbor need to kind of check their attitude and that the city doesn’t need them to come save it,” Shipp says. “They don’t mind people coming down to help contribute towards the city’s rebirth, but they don’t want people coming down on their white horse in their white hat thinking they’re going to personally fix the city on their own.”

That’s a problem close to the heart of young, relatively new Detroiter Joel Batterman. Batterman, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in urban planning at U-M, grew up in Ann Arbor. He moved to Portland, Ore. to pursue his bachelor’s degree, but moved to Detroit in 2012 out of a concern that he was “taking white flight to the next level.”

Batterman says he’s sought to be “useful” to his new community through political activism, working to pursue better housing opportunities, regional transit, and desegregation policies.

“It shouldn’t be a colonial project,” he says. “It shouldn’t be a question of affluent, educated Ann Arborites or their children colonizing Detroit, but rather … a partnership between the communities.”

Meanwhile, there’s not necessarily a comparable influx of Detroiters visiting to see what Ann Arbor has to offer. Tobier regularly brings the Detroit high school students he works with to Ann Arbor, where he says they’re fascinated by the community’s “dense retail street life” and walkability. But transportation and financial issues still prevent many Detroiters from making the trip west.

“When you realize that you can travel from one place to the other, you don’t see the accident of your birth or the coincidence of where you happen to live as the surrounding parameter of your ambitions for either work or for your future,” Tobier says. “You see it as accessible and possible, that this is part of my life if I choose it.”

Building connections, literal and otherwise

So what are the most productive solutions to bridging the gap between the two cities? The stakeholders we talked to agree that a better relationship boils down to residents of both cities being more mindful about how they can help, and be helped by, each other.

“I think people in Detroit need to think of Ann Arbor as a place to utilize, to help make the city better,” Shipp says. “For people of Ann Arbor, it’s about understanding there’s kind of a wider world, that everything’s not as hunky-dory as it is in Ann Arbor and we can help.”

Beyond these psychological shifts, Staebler suggests that any kind of regional transit between the two cities would also improve the disconnect in a very literal way. “When I told somebody in Detroit, ‘Oh, I live in Ann Arbor,’ they wouldn’t go, ‘Oh, that far away?'” he says. “They’d say, ‘Oh, do you take that cool commuter train?’ like they do in every other city in the country.”

A millage to authorize a regional transit system for Wayne, Washtenaw, Oakland, and Macomb counties failed to win voters’ approval this past November. But Staebler says he wouldn’t be surprised if the Regional Transit Authority of Southeast Michigan (RTA) retooled its efforts to focus only on Wayne, Washtenaw, and southern Oakland and Macomb counties, where the millage did well.

Smith says Washtenaw County’s enthusiastic support of the RTA is one recent strong example of the way Ann Arbor should view Detroit.

“We knew that investing in transit in the city of Detroit was going to be a benefit to everybody in the long run, and it would be a greater benefit to the residents of Detroit in the short run than it would be to the residents of Ann Arbor in the short run,” Smith says. “We need more of that kind of thinking, a recognition that it is in both our moral interest and our selfish economic interest to make sure that impoverished communities are lifted up. I would hope to see us doing more of that kind of work.”

Batterman suggests that the two communities should endeavor to act more as collaborators in a “joint project” that benefits both of them.

“When it comes down to it, we are all in this together as a metro region,” he says. “Obviously some of us are much more privileged than others, but we all have an interest in building a better future than the one we’re currently facing in this state.”

Photos by Doug Coombe.