Weekend pedal: A Kalamazooan tours Detroit at the ‘speed of bike’

What better way to visit Detroit than by bike? Writer Mark Wedel, an avid cyclist, decided to test his pedal mettle in the Motor City. He discovered a bicyclist's urban nirvana.

Weekend Pedal, Part I

I felt safe in Detroit.

If you’re riding a bicycle, you’re not safe anywhere. But I felt safer in Detroit than in my hometown of Kalamazoo.

On a bicycle, you are exposed to everything vibrant and unique in a city. Detroit was almost too much for me — a good too much.

Detroit is a city built too big for its current population. Wide, expansive streets chop up the Motor City, but the traffic they were built for seems to be gone.

How should Detroiters use all that pavement, with so few cars?

Since the 2010s, Detroit’s bike culture has grown naturally, along with many miles of bike lanes and greenway paths. Some residents realized that bikes could be a part of daily life.

Michigan Central has been holding free open-house hours on weekends since June’s grand opening. Lines may be long.

Last spring, visiting the Detroit Institute of Arts as part of the usual American car trip, I noticed people on bikes going about their day. I saw bike lanes down most of the city’s arteries, with Cass Avenue taking you almost all of the way downtown on a lane protected by bollards. Other roads, with bike lanes or not, are multi-lane, but can be weirdly deserted much of the day.

Since 2012, I’ve gotten in the habit of bike touring, trips of 300-700 miles over a week or two, once a year. I’ve seen a lot of West Michigan, the top of the Mitten, a lot of the UP. But not much of the east side of the state.

Ride in Detroit? Instead of riding through state forests and along the shores of the Great Lakes? I can hear my father, who refused to take us into Detroit on family vacations to Greenfield Village in the ’70s because surely we’d be mugged and our car stripped for parts, ask me, “Are you nuts?”

What if I just took a weekend, got myself and my bike on the Amtrak to Detroit, stayed in one spot each night, and simply pedaled around in the city?

Bike tourism in Detroit — is that a thing?

“I love it!” Chris Dilley says, laughing at the question. “I mean, that’s all I did for the last year” — that is, load his old ’90s mountain bike on the Amtrak in Kalamazoo, and head east to ride in Detroit.

I talked with Dilley in Kalamazoo before I headed to Detroit. He’s been the long-time general manager of the People’s Food Co-op (PFC) of Kalamazoo.

His bike and the Qline were how he got around as he served as a consultant at the start of the Detroit People’s Food Co-op. Dilley helped the Black-led and community-owned cooperative get fresh and healthy food to the food desert of the Virginia Park neighborhood. “It was a great gig,” he says.

Dilley says he had mainly positive experiences on his bike in Detroit. A driver yelled at him as he slowed traffic in a tight construction zone, but that was his only negative moment.

Detroit is rebounding from its 1970s-1980s reputation as being a dangerous and declining city. “In the community that I was invited into, (there is) definitely a sense of positive momentum and change in a good direction,” Dilley says. There is movement in “building things that actually matter to the Black community in particular there, which is great.”

Day One: Stopping at Seasons Market and Cafe, waiting for check-in time at the El Moore.

Bike infrastructure, and other efforts at making biking easier and safer, “probably isn’t top of mind as far as the needs of the community,” he says. “But it’s definitely seen as positive.”

Dilley was willing to pedal anywhere in the city, except on Woodward Ave. — a bike tire can be captured by the ruts of the Qline tracks, leading to disaster, he points out.

“Everybody there knew that I rode my bike everywhere, and they were concerned about my well-being,” he says with a laugh. “I appreciated that.”

He knew he was an outsider, a white guy from Southwest Michigan on a bicycle. “It’s a Chocolate City, as they say. There’s amazing amounts of black-owned businesses and efforts.”

Dilley recommends riding on quiet neighborhood streets to make a safe, calm route through the city. But, of course, this is where people live, Detroiters’ homes. If one were to ride around as a tourist, one needs to have some respect for the community, Dilley says.

The Southwest Greenway features The Yard Graffiti Museum. Much of Detroit’s public art is, or is inspired by, graffiti.

One should visit without “that sense of entitlement or whatever that comes with feeling like it should be different or more comfortable or whatever,” he says. “Letting that go is helpful because then it lets people know that you’re seeing them.”

Biking is the opposite of viewing another community through your rolled-up car window, doors locked. On a bicycle you show that you’re fine with being exposed to whatever the city has to offer you, good or otherwise. You see and hear everything.

“You see it at human scale, right? That human speed. I love that about it,” Dilley says.

Dilley had a list of attractions I needed to check out: the Lincoln Art Park and its unusual sculptures, a tiny brewpub with the best Detroit pizza, the stalls of the Eastern Market on a Saturday, and the graffiti of the Dequindre Cut greenway.

On a bike, Dilley got a granular, detailed view of Detroit. “That was the highlight, just being able to pull over and meander through things like that because you’re going at the speed of bike, you can just notice there’s something interesting over there and it’s not a problem to pull off or turn around.”

Big city, shrinking population

I packed one pannier with essentials and used a front bike bag for the overflow. Pedaled my Priority 600, a sturdy commuter designed for urban use by a New York City company, from our home to the Kalamazoo station. Hefted it all up the steps of the 350 Wolverine.

I’ve done a few bike/train trips. Amtrak’s bike service, reservable for $10 with your ticket, is a bit erratic, but doable. To board larger cross-country trains, you hand your bike up to staff who safely stow it in the baggage car. But smaller, regional trains require you to haul your bike up steep steps, through narrow passageways. Large bags must be off the bike and carried separately. On the train headed east, I had to bungie the bike to a railing. Going back home, a newer car meant Amtrak’s new bike hooks — I had to lift the bike up, and hang it from its front wheel on a hanger.

The author’s Priority 600 in front of the Temple Bar on Cass. The dive bar is a frequent setting on the 2017-2018 Comedy Central series “Detroiters.” Unfortunately, it’s closed indefinitely.

You might get help from the conductor and staff. But their priority is getting everyone on board in the time allotted for the stop. If the train is late, be ready to hustle.

I got off the train Friday afternoon at the station on Baltimore and Woodward. I resisted going across Woodward to get a photo of my bike with the White Castle sign. Woodward traffic at that time of the day seemed to match my worse urban fears, so I headed to Cass.

The El Moore, where Wedel stayed.

Cass Avenue has a protected bike lane, so I headed south on it, by Wayne State, deep into the heart of Midtown. It was easy enough to find my home for the weekend, the El Moore.

The Alexandrine Street building began in 1898 as luxury apartments, became a cheap boarding house after the Great Depression, was home to artists and radicals in the ’60s and ’70s, and by the ’90s was an abandoned wreck, until 2010 when it was redeveloped into environmentally sustainable apartments and hotel rooms.

I chose it because its history is much more Detroit than, say, the hotel at the downtown casino. Plus, the cost of a three-night stay in the El Moore’s suite, with a full kitchen, is comparable to three nights in a regular room downtown.

Detroit’s population dropped from 1.8 million in 1950 to 638,300 in 2020. Many neighborhoods are dotted with empty lots. One of few structures on Pierce St. is this AirBnB.

It was a good, central base for explorative activities.

I was excited — I’m used to 50-mile days on bike tours, heavy bike loaded with bags of camping equipment, clothes, food, water and gear.

I mapped out Detroit routes to points of interest, and realized a busy day could be under 20 miles.

Less than two miles to Michigan Central? Easy. I unloaded my stuff, studied the map, and headed out. Pedaled east on Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd, south on 14th, though North Corktown.

The neighborhood had a lot of empty lots, mowed and well-kept, but looking as if a disaster happened there many years ago. It felt like I was riding past the ghosts of homes.

Suddenly, there’s the huge 1913 train station looming ahead, that’s been a symbol of Detroit’s blight and decay for half a century.

The author enjoys an old fashion, Creole bowl and live R’n’B. Food and drink trucks, and live music keep the Michigan Central grand opening going on weekends.

This summer, it’s alive. After refurbishing ended in June and its grand opening celebration, it’s been a spot of continuing weekend public parties and a free open house for anyone who wants to look inside.

I locked up the bike at handy new bike racks, got a “1913 Old Fashioned” from a bar truck, a Creole bowl from a Black-run food truck, and sat to watch a live R’n’B cover band. My photos show the celebration space on the lawn being pretty empty, but I was there early. People of all varieties wandered in and stayed over the next hour.

A huge line of people waited to get a look inside Michigan Central. I decided that Saturday morning might be a better time, and the line was just as long the next morning. No matter, it was a short bike ride. Bikes lend a particular kind of flexibility to one’s day.

“The Spirit of Detroit.”

Saturday morning I waited to see the inside of this temple to public transportation. After spending time in the utilitarian Amtrak station in Baltimore, seeing Michigan Central I wondered if the people of the past worshiped the train as their powerful new god.

It opened the same year Henry Ford started mass-producing his noisy automobile machines. The station was the Midwest’s link between East and West, between the U.S. and Canada. Streetcars linked it with a growing and increasingly wealthy downtown Detroit. It was known as Detroit’s Ellis Island, with millions arriving from outside the country, or from other parts of the U.S., to find a new life.

A few days later, waiting for the Amtrak back to Kalamazoo, I talked with a couple from Belgium, who were bike touring through the U.S. One said of their experience riding in Detroit, that they were amazed at desolate areas where it looked like “a bomb went off…. like there was a natural disaster.”

An outsider might assume a singular disaster happened. “White flight” and the riots of 1967 and 1968 — referred to as the “uprising” by some Detroiters I talked to — are usually blamed for Detroit’s descent.

A way to get around Detroit by pedaling: the pedal bar.

But charts show that the city hit its peak of 1.8 million in 1950, and started its steep fall that decade, years before the riots.

Many also blame the struggle of Detroit’s auto industry as a reason for the decline. Foreign cars became popular, and factories closed or relocated.

Also of note, starting in the middle of the last century entire neighborhoods were destroyed and people displaced to create the network of interstates that divide the city.

There are efforts underway to find remedies, to cap I-75, and to remake I-375 into a neighborhood-friendly boulevard.

For all those reasons and probably others, Detroit’s amazing growth reversed in 1950, dropping to 638,300 in the 2020 Census. Its population density is very low compared to other cities.

Huge infrastructure upkeep and a low tax base aren’t healthy for a city, to state the obvious.

So, the city built for, and by, cars now has a lot of pavement that’s weirdly empty most days. Which is good for biking, but a sign of a city that still has an uncertain future.

Detroit renaissance

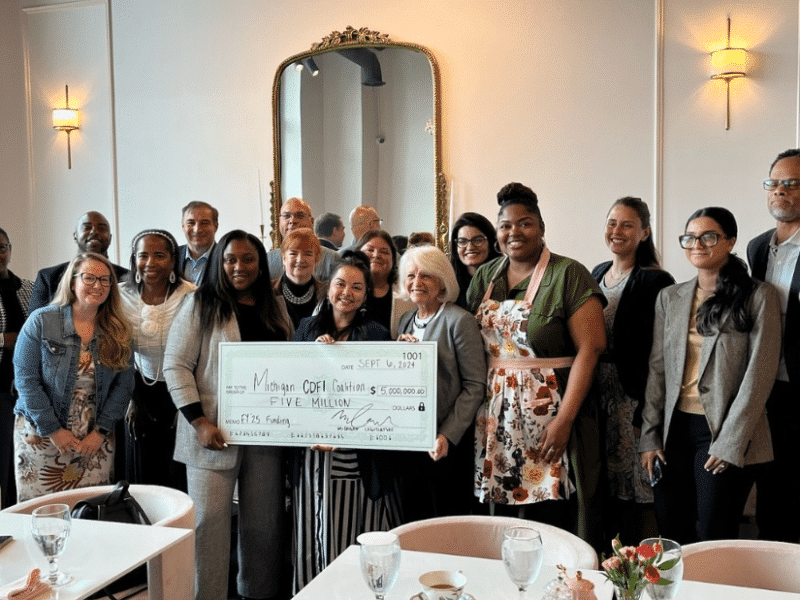

Maybe with obvious irony, since privately-owned cars killed public transportation, but also with a helping hand, the Ford Motor Company invested $950 million into restoring Michigan Central.

The goal is more than just to make an old building grand again — with the City and the State of Michigan, Ford is creating a “Transportation Innovation Zone” in and around the old station.

Bikers headed for Michigan Central. Now restored, the train station had been a symbol of Detroit blight since 1988.

Detroit is also investing $1 billion to create affordable housing by the zone, breaking ground for new units in North Corktown in late July.

Efforts like this promote a Detroit Comeback narrative, and who knows — the rate of decline in population seems to be reaching a plateau.

Detroit at the speed of bike

After a food truck dinner in the shadow of Michigan Central Friday evening, I jumped on the bike to explore.

I headed toward the river from Michigan Central on a nice, new connection to the Southwest Greenway. Families were strolling past potted plants, under decorative lighting along what used to be a grimy alleyway. It was all part of what will be the over-27-mile Joe Louis Greenway, which will form a large non-motorized loop connecting neighborhoods from Highland Park to downtown.

It was a perfectly pleasant ride, through the Southwest Graffiti Museum, south to W. Jefferson Ave., along the river.

Again, I expected the worst from a five-lane, super wide road, but Jefferson was deserted. Construction between the river and road, and a lot of fencing, made for a bleak urban environment. I had to dodge broken glass. On my bike, I could imagine being in some sort of post-apocalypse movie.

I noticed in my rearview mirror a group of bikers behind me. I heard them before I saw them. They were blaring music.

I pulled over to see what kind of bloodthirsty horde was behind me. They passed with a number of cheery “Wooo!!”s and waves. One had a Bluetooth speaker blasting party tunes.

They were headed to the riverfront, so I followed the rolling party. From a shouted, moving interview I found out they were the Rustbelt Riders, a bunch of attorneys and friends from the area, who do a Detroit ride once a year.

It was before sunset, Friday night. Crowds of people — in wealthy attire, clubbing attire, casual tourists from Europe and Asia, families and kids, rollerbladers and other bikers — packed the RiverWalk. Pleasure craft and jet-skies were in party mode on the water. On the other shore, Windsor was doing whatever Canadians do on a Friday. Ahead, the RenCen looms up above everything.

Michigan Central was built in 1913, and was the arrival point for many as Detroit’s population exploded in the early 20th century.

The Rustbelt’s DJ switched to Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” — I suppose this is “South Detroit” — and the people we carefully weaved around gave us a few positive affirmations.

We flowed like a river, through Milliken State Park, and up the Dequindre Cut.

The Rustbelt gang pulled off to where their cars were parked. I bid them farewell and rode on. It felt like something magical just happened.

What that something was telling me was, don’t let your plans dictate the ride. Things will just happen in this city.

Saturday and Sunday I simply wandered. I set goals of what I needed to see, but got distracted easily.

Saturday morning, after seeing the inside of Michigan Central, I went to the RiverWalk again. This time I stopped at every whim.

To be continued. . .

Will Wedel enjoy a coney island dog and Better Made chips on the RiverWalk? Will he be able to sneak into the Belle Isle Aquarium? Will he join what appears to be a biker gang, to pedal with them on Detroit’s midnight streets? Will he find a new biking home in the city’s “slow roll” culture?

Editor’s Note: To find out where his whims took Mark during his weekend bicycle tour of Detroit, check back on Thursday, September 5, for our second installment.

VIDEO: A regular bike ride down the Cass Corridor’s protected bike lane on a Sunday afternoon.