Why Detroit needs a plan for tree equity

Using national datasets, Planet Detroit identifies outliers pointing to places with equitable or growing tree canopy, particularly in historically underserved locations, and reports on the solutions those places have found.

This story was originally published in Planet Detroit.

Disease has wiped out many of the trees that once grew around Robert Turner’s house near 6 Mile and Schaefer highway. He says the trees first started coming down in the 1960s, many of them victims of Dutch elm disease. Then in 2002, the emerald ash borer, first discovered in Detroit, took out a few more.

Those trees might’ve provided a bit of relief against the heat that baked Turner’s house this past August. Turner, 68, said he’s not sure if climate change caused August’s high temperatures, although he believes it is a problem. Either way, he’d like to see leaders do more to protect Detroiters from extreme heat.

“Not everyone can afford even to buy fans,” he said. “So, you know, it gets kind of bad.”

Trees play a crucial role in helping people stay cool in the hot summer months. They shade homes, streets, and other hard surfaces, radiate heat trapped during the day, and contribute to the urban “heat island effect.” These heat islands can become even more pronounced at night, preventing people from cooling down and making severe heat illness more likely.

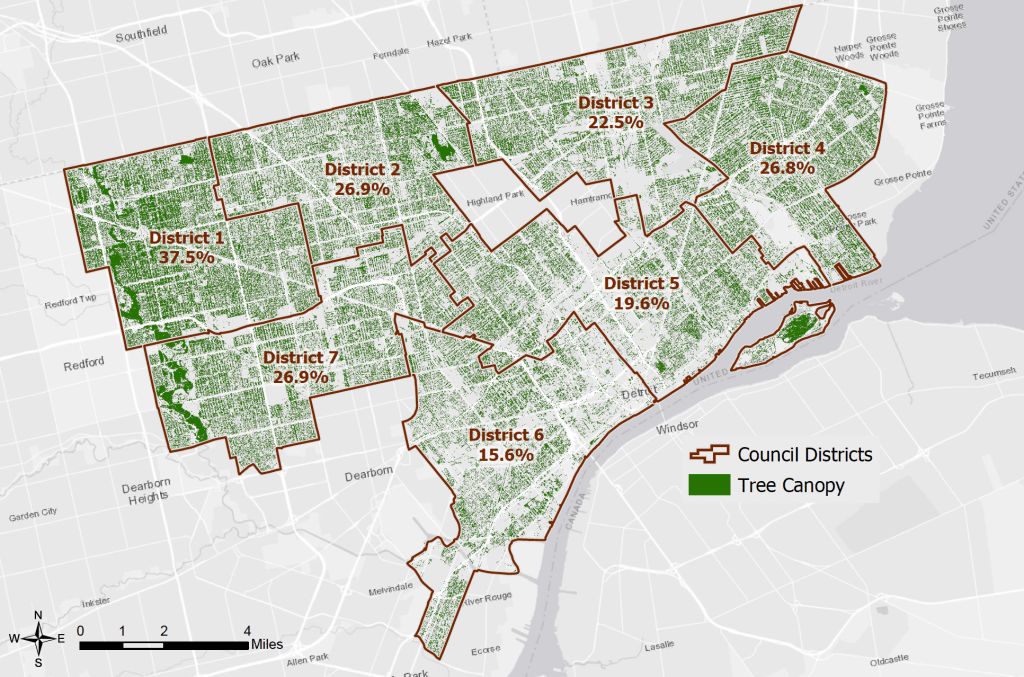

Neighborhoods with good tree canopy coverage–which are often whiter and more affluent–can be between 5 and 20 degrees cooler than areas with fewer trees. But Detroit would require a massive acceleration in tree planting efforts to provide the 30% canopy coverage that Eric Candela, manager of the Community ReLeaf program for American Forests, says is ”the floor for a healthy city.” American Forests recommends Detroit shoot for 40% tree canopy coverage; in 2017, the city measured its tree canopy coverage at 24%.

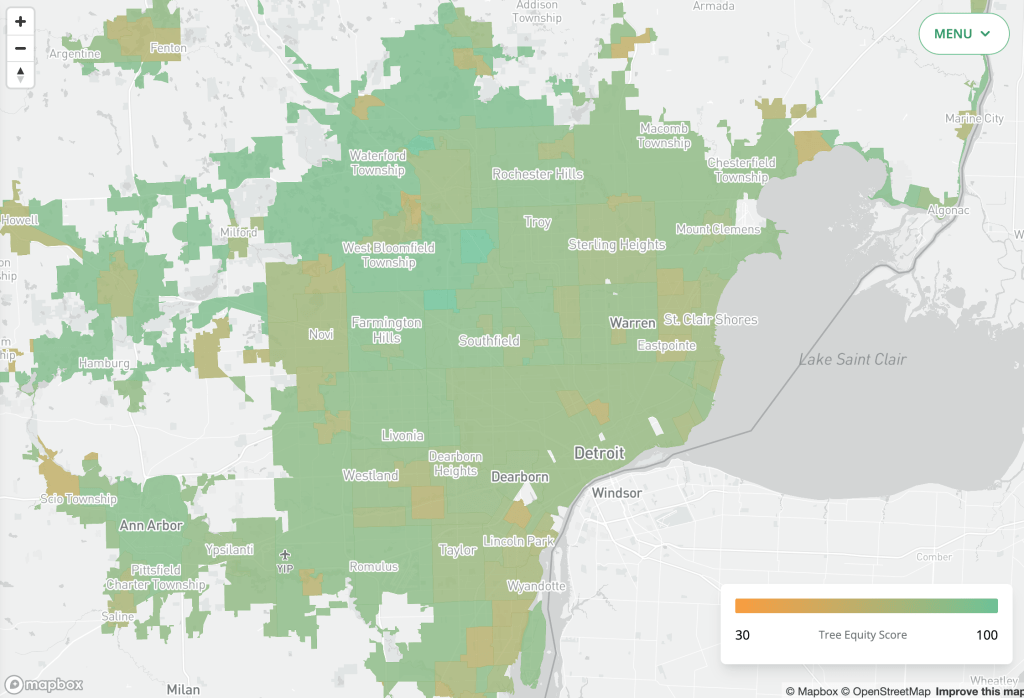

Moreover, Detroit lacks “tree equity,” according to data produced by American Forests in 2021, a metric it developed that assesses whether the health, climate, and economic benefits associated with a healthy canopy are equitably distributed across socioeconomic boundaries.

Formerly redlined communities like Detroit often face this challenge; disadvantaged neighborhoods of color have fewer trees, while wealthier, whiter neighborhoods enjoy healthy tree canopies. And that means more heat exposure during heat waves and worse air quality.

Research documents that formerly redlined neighborhoods of major cities are often more than five degrees hotter than other areas. And American Forests’ data reveals how one crucial factor is driving this discrepancy: these areas often have fewer trees.

Overall, Detroit has a tree equity score of 80, above Cleveland and St. Louis, but behind Chicago and New York. And 286 of its 875 block groups score below 75; some as low as 36. American Forests estimates Detroit will need at least 282,019 more trees to get every neighborhood to its minimum target tree equity score of 75.

The nearest tree to Turner’s home is at his next-door neighbor’s house, too far away to provide any shade. He said he believes the city’s heat response should include cooling centers and help people to buy air conditioners, but he would also like to see more trees in the neighborhood.

“I think that if trees were taken care of properly in neighborhoods, as opposed to just letting them grow to a point where they can’t be cared for properly, that would help with keeping it a little cooler,” Turner said.

Heat, trees, and equity in Detroit

Mel Herrera lives in a section of Detroit’s Islandview neighborhood that received a tree equity score of 86 from American Forests, above average for the city. But the lack of shade on her corner means the sun cooks her bedroom for most of the day, making it too hot to spend time in except to sleep.

She has a window air-conditioning unit in the living room and plans on getting another one for her bedroom next year. During this August’s heat, she went to her boyfriend’s house to sleep for several nights because he had central air.

The people Planet Detroit spoke with had some access to air conditioning, either in their homes or elsewhere. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, cooling own for even a short period can be crucial for preventing heat illness.

According to Dr. Ijeoma Nnodim Opara, an internal medicine pediatric physician serving a predominantly African American population in Detroit, chronic heat exposure translates into higher rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease and direct effects like heat stroke and heat exhaustion. Other stressors in formerly redlined areas like poverty and water shutoffs can exacerbate these health problems, she said.

Nnodim Opara stresses the importance of adequate hydration and staying inside during the hottest times of the day. She says that while measures like Detroit’s cooling centers can help as a “temporary measure,” more is needed to keep people cool at home. Research shows that people avoid cooling centers for several reasons, including because they don’t see themselves as sufficiently vulnerable or don’t know the spaces are available.

A healthy tree canopy offers a low-cost, distributed cooling mechanism for cities that could address some of these inequities, shading buildings and other surfaces and lowering temperatures through evapotranspiration (the evaporation of water from leaves and other surfaces). Shading can cool surfaces by 20 F to 45 F, and evapotranspiration can reduce air temperatures by 2 F to 9 F.

Trees could also cut down on the need for air-conditioning, which the World Economic Forum calculates could produce as much as 0.5 C degrees of additional global heating by the end of the century on account of its energy use. And waste heat from air conditioning can lead to higher nighttime temperatures in cities, creating a cycle of higher temperatures and a greater need for cooling.

For those periods when air conditioning is essential for safety, trees can make it more affordable for the one-third of Michiganders who worry about paying their utility bills. Of course, the urban forest is already helping in many areas, shading buildings in summer and acting as a windbreak in winter. The United States Forest Service (USFS) found that heating and cooling bills in US homes would be more than 7 percent higher without trees.

Detroit’s patchwork approach to tree canopy management

If Detroit were to try and achieve American Forests’ target of getting each neighborhood to a recommended minimum tree equity score of 75 over the next two decades, it would mean planting 14,100 trees or more each year. In 2017, the city of Detroit pledged to plant 10,000 trees, with more than 5,470 planted so far, according to Angell Squalls, a city forester. Yet, these numbers may not even be enough to keep up with the annual rate of die-off, which a 2016 study from Davey Resource Group estimated could fell as many as 5,123 trees a year.

While progress has been slow, American Forests’ Candela is optimistic about the future. In 2016, American Forests convened the Detroit Reforestation Initiative, a coalition of government, nonprofit and university partners to build capacity around tree canopy management. The group includes city department staff, representatives of the U.S Forest Service, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, and the nonprofit Greening of Detroit.

In that time, the coalition has helped complete an urban tree canopy analysis using LIDAR, an aerial mapping technology. It also helped develop two tree nurseries within the city at Meyers Nursery in Rouge Park, operated by Greening of Detroit and operated by Herman Kiefer Development, a private development company. They also secured $260,000 over three years in Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) funding to plant trees to mitigate stormwater in Detroit’s Delray neighborhood.

But Erin Kelly, a landscape architect and certified arborist working in Detroit who worked for the city’s planning department between 2016 and 2019, said what the city needs is a coordinated plan to address tree canopy management. “There’s nothing happening systematically,” she said.

Kelly points to the Cleveland Tree Planting Coalition as an example Detroit might follow. Like the Detroit Reforestation Initiative, the group is comprised of public, private, and community groups setting goals for tree planting and securing resources to achieve them. In 2018, the coalition announced a goal to plant 361,000 trees over the next decade, although by 2020, they had only planted 12,000. The Cleveland group provides a comprehensive plan with goals, targets, and metrics, which Detroit so far lacks.

So far, according to Candela, Detroit has not initiated such a coordinated plan. “One of the Detroit Reforestation Initiative’s goals has always been to help Detroit increase urban forestry capacity throughout the city,” he wrote in an email. “That’s as specific as we’ve defined it for the time being.”

In the absence of a coordinated plan, individual entities make dents in the problem in their own ways. According to Squalls, the city allocates $2 million to plant trees along rights-of-way and $3 million for tree removal. In addition to the 5,470 trees the city has planted, it has so far exceeded its goal to take down 10,000 dead, dying, or nuisance trees by 700 trees, according to Squalls.

Meanwhile, the Greening of Detroit, which once operated as the city’s forestry arm, continues to plant several thousand trees a year, including plantings in public parks that are not addressed by the city’s forestry program, according to the organization’s president Lionel Bradford. He said that since the organization’s inception 32 years ago, The Greening has planted 130,000 trees.

“I think we’ve helped to move that needle a little bit,” Bradford said. “But there’s still a ways to go to get to that 40% tree canopy goal.”

Building a constituency for trees

Christina Ridella, a volunteer and community outreach coordinator for The Greening of Detroit, says that trees can be a tough sell for Detroiters. That’s because of a history of poor maintenance that has left the canopy vulnerable to storms, which can cause falling limbs that damage cars and houses or take out power lines and cause blackouts.

“You find your tree advocates and then kind of work from there,” Ridella said. “A lot of times, the neighbor is going to convince them even more than me. We’ll put information on the fliers and make sure that it’s spread out and then go from there.”

Candela also stressed the importance of using neighborhood organizations to reach out to residents. “It just stands to reason that if the person who’s talking to you about tree planting lives in your community, it will be a much more fulsome conversation,” he said.

The Eastside Community Network (ECN) is one group working with American Forests on community outreach and planting trees. Tree planting and green infrastructure were a part of the Lower East Side Action Plan–which involved extensive community outreach by ECN.

The Detroit Reforestation Initiative is working with the U.S. Forest Service to assemble a stewardship map or “Stew Map” of organizations in the city that are interested in tree planting–even if it isn’t central to their mission. That map can help connect groups with funding and resources to further reforestation efforts.

A new collaboration between Michigan State University, American Forests, and the U.S. Forest Service called “Engaging Detroit Communities through Reforestation across Six Different Site Types” is one place where this leg work could be helpful. The GLRI-funded research project in Detroit’s Delray neighborhood aims to use urban forest patches to protect water quality and perform phytoremediation (using plants to remove soil contaminants or render them less bioavailable).

Planting more trees in Delray could also align with groups like the Southwest Detroit Community Benefits Coalition, which aims to protect residents from the air pollution and noise created by the Gordie Howe International Bridge. The bridge has already displaced several residents and could bring 50 percent more traffic than the current border crossing.

The researchers say the Delray effort could demonstrate the potential of urban forest patches to cool cities with more concentrated plantings than can be achieved with street trees. They’re hoping to add to a developing body of research that looks at how different sizes of forest patches contribute to city-wide cooling and whether specific configurations can provide more significant benefits than others.

“As we’re learning more about forest patches, we understand that they have a regional cooling effect that’s disproportionate, in a good way, to their size,” said Sarah Hines, science delivery specialists at the U.S. Forest Service.

She added that lessons learned in Delray could apply to several sites in the Great Lakes region and beyond, demonstrating how to reestablish forests in formerly industrialized areas, turning them into low-maintenance natural areas.

However, it’s unclear how long the plantings here will last. A plan put out by the city of Detroit shows that some trees will eventually be replaced with “future industrial” land uses – while other remediated areas might be transitioned into permanent buffers to help deal with pollution and noise.

Asia Dowtin is a professor of urban forestry at Michigan State University and the lead investigator on the project for Michigan. She says her team plans to work with community members from the outset to let people know what trees can do for their neighborhood and identify species that interest them. She stressed that while Delray’s industrial past and surplus of open space make it a good candidate for this undertaking, its people are just as important.

“There’s already a level of investment in the community in terms of interest in seeing some form of restoration,” Dowtin said. “We knew that there’d likely be community buy-in and long-term partnership and stewardship.”

Another potential benefit of the Delray project could be to inform tree planting in Detroit’s parks. The city’s budget restricts tree planting to public rights-of-way, meaning parks and other open spaces get neglected in favor of street trees. Kelly, the landscape architect, said a plan to reforest parks and open spaces with tree patches could be beneficial for reforesting Detroit.

Detroit clearly would benefit from planting many more trees to help it respond to an accelerating climate crisis. But while what’s happening in Delray may be a good start, an overarching plan to reforest the city has yet to emerge.

According to Kelly, that plan doesn’t necessarily need to come from the city government. In the past, Detroiters have expressed frustration with city leadership over a lack of vision on environmental issues. And while some level of city buy-in and support would be necessary for a tree-planting program, Cleveland’s experience and Detroit’s Reforestation Initiative show that citizens, nonprofits, and other entities can influence what their city’s tree canopy looks like.

“When you see a city that has a tree plan and goals,” Kelly said, “the plan happens because someone cares. It doesn’t need to be the mayor.”

Rukiya Colvin contributed reporting to this story.

ABOUT THIS SERIES: As part of Planet Detroit’s ongoing solutions-based reporting on environmental justice and equity, we took a deep dive into the national and local data on tree canopy and tree equity. With funding and collaboration from the Solutions Journalism Network, Planet Detroit reviewed a variety of national datasets, including data on tree equity from American Forests and redlining data. We aimed to identify outliers pointing to places with equitable or growing tree canopy, particularly in historically underserved locations. We then reported on the solutions those places have found to build equitable tree cover. Read the full series here.