Detroit designer combines fashion and science to start a conversation about skin color

Detroit entrepreneur Deirdre Roberson doesn't fit a mold. And the scientist-turned-fashion-designer doesn't want you to, either. “People will say to me ‘you look like a model,’ but why did nobody ever tell me ‘you look like a scientist’? We are complex. We are multidimensional people.”

Deirdre Roberson refuses to be defined by just one part of her life. Scientist, designer, entrepreneur, and model are only a few of her roles, and she’s made a business out of dealing with shades of complexity. Literally.

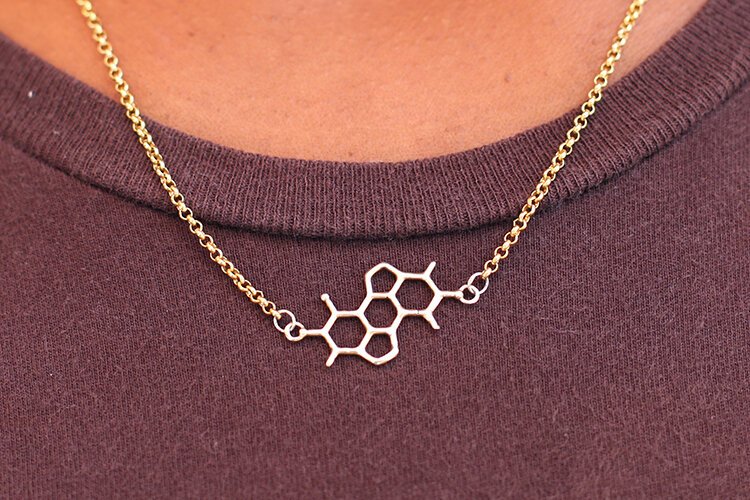

Roberson’s Detroit clothing line Eumelanin (pronounced “you-mel-a-nin”) comes in many colors of human skin tones, with the aim of starting a dialogue about our visual differences. The fashion brand bears the chemical structure of melanin — the natural pigment that is responsible for skin color.

Appalled by the implied racism of skin-whitening creams sold around the world, Roberson set out in 2018 to start a conversation about the aesthetics of skin, and wants her customers to celebrate their shades.

“To have Black skin is to be looked down upon,” she says. “What better way to change that than through fashion — something we deem ‘beautiful.’ ”

Roberson has long had a foot in both fashion and science, but it’s always been a delicate balance for her. Growing up in Southwest Detroit, she started sewing as a way to earn money at the age of 13, after taking a middle school home economics class, and began working out of a studio at home.

“Neighbors would want things adjusted,” Roberson says. “Dresses, pants, things like that. I remember one pair of Versace pants, and I was thinking ‘if I mess up this woman’s pants it’s going to be crazy,’ but she trusted me. I can’t get that out of my head.”

Her passion for clothing design grew from there. But, she admits nostalgically, fashion didn’t offer the job security she wanted. So she went into the science field, majoring in chemistry at Xavier University in New Orleans and earning a master’s degree at University of Detroit Mercy. She worked for the City of Detroit as an environmental scientist for three years, and is now part of the STEMinista Project at the Michigan Science Center.

It was after drawing social media support for wearing her own creation (a bright yellow sweatshirt) at a Motor City S.T.E.A.M. Foundation event, that she decided to launch her own label.

Connecting her love of science, design, and business made sense to Roberson and the self-proclaimed “entrepre-noir” says it allows her to discover different parts of herself. It’s not something everyone recognizes.

“People will say to me ‘you look like a model,’ but why did nobody ever tell me ‘you look like a scientist?’ ” Roberson asks. “We are complex. We are multidimensional people.”

“Growing up as a Black woman in Detroit in a very diverse area, I had to learn how to maneuver the world as a Black woman, as a Black scientist,” she says.

Maneuvering is something Roberson has mastered. The businesswoman has made an art of leveraging resources around her, connecting with Build Institute, TechTown Detroit, ProsperUS Detroit, and taking courses at the University of Michigan.

“I have been a part of every free entrepreneur course in Detroit,” Roberson says. “I have always been very resourceful — it has allowed me to get the knowledge I needed to get my company tight.”

Roberson started out selling her creations on Facebook, and then built her own website, officially launching on March 22, 2018. Her start date was on her grandfather’s birthday as a way to pay homage to his influence in her life.

“Within the first four hours I had over $1,000 in preorders,” she says.

Since then, Roberson has been steadily growing her brand, and has been very intentional about the materials she uses and which local artists and manufacturers she partners with. Her jewelry range, for example, is designed by a Black artist and uses only silver and gold.

“Those metals are ones that hold value, and I want people to value themselves,” she says.

The COVID-19 pandemic depleted most of Roberson’s event revenue this year, an estimated $30,000 to $50,000, and she had to cancel a talk at the popular South by Southwest festival. But the entrepreneur received acclaim, and $10,000 in funding, as one of the winners of a New Voices + Target Accelerators Pitch competition, and says her online sales “skyrocketed” after the announcement.

“It means a lot to me,” she explains. “When I was founding this brand people just didn’t get it, people told me racism doesn’t exist anymore. Now look where we are.”

Roberson’s goal to celebrate diversity, and business campaigns such as #WhenWeSeeOurMelanin, is highlighted against the backdrop of recent protests across the U.S. over racial prejudice. Eumelanin is known for its pop-up “melanin wall,” which has appeared at locations like Corktown, displaying different skin shades and encouraging people passing by to take selfies.

“What Detroit is going through right now — it’s important for us to be present,” Roberson says.

Roberson isn’t alone in her desire to use clothing to spread a message. Fashion, historically, has been a powerful tool of social movements. Sashes and white dresses used by the suffragette movement, the Black Panthers’ iconic black berets, and the pink “pussy hats” of the Women’s March are examples of signaling solidarity. More recently, Black Lives Matter activists have donned COVID-19 masks and T-shirts bearing the words “I can’t breathe” and “Assata taught me” as symbols of the movement.

But does clothing have the power to change entire social attitudes? Jo Reger, a sociology professor at Oakland University, says it can be the beginning of a cultural shift and a way for movements to educate the public on the changes they seek.

“Most simply seen in a T-shirt with a slogan, social movement clothing styles can be more complex through wearing certain colors or images such as rainbow items for the LGBTQ+ community or adopting styles such as the overalls worn by white students active in the civil rights movement,” Reger says.

Reger draws comparisons between the message Roberson focuses on and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, describing the label as a “positive force.”

“Eumelanin is celebrating Black and Brown lives and beauty and bringing science into discussions of racism and white privilege.”

Despite the aligned messages, Roberson was reluctant to shape a marketing campaign around the BLM movement.

“Activism is already built into the brand,” she says. “People wanted to wear the shirts to protests and talks, and it’s been organic. We didn’t want to capitalize on that.”

“Our work can always be part of social change,” says Roberson. “Sometimes it’s just connecting the dots.”

“I am just getting started.”

This is part of a series supported by LISC Detroit that chronicles Detroit small businesses’ journey in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.