Detroit parents ask Michigan candidates how they plan to address air quality and asthma concerns

Parents and childcare advocates recently showed up at a virtual forum to ask local candidates running for Michigan's State Senate this November about the issues on families' minds. Check out what those looking for your vote had to say about low air quality and high asthma rates affecting Detroit's children.

With November’s election around the corner, parents want to know which electoral candidates will prioritize the issues they’re concerned with most. Air quality, access to asthma treatments in schools, funding for universal preschool, childhood mental health and students with special needs, affordable child care that offers living wages for staff, and early education teacher shortages are all on their minds. Many held electoral candidates accountable through their questions at a forum recently.

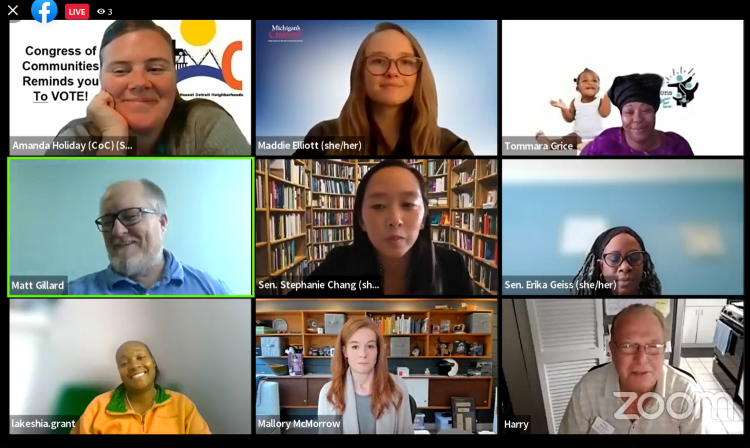

Detroit Champions for Hope, in partnership with Michigan’s Children, hosted the virtual forum on Oct. 24 for parents to ask local candidates running for Michigan’s State Senate about the issues on families’ minds. Congress of Communities in Southwest Detroit and Think Babies Michigan also sponsored the event, which streamed live on Facebook.

An early childhood initiative of the Hope Starts Here Framework, Detroit Champions for Hope, connects parents and caregivers to resources and advocacy, supporting them as children’s first champions. Michigan’s Children works in pursuit of public policy in the best interest of children and families from cradle to career. The nonprofit collaborates with local partners across the state to host youth and parent-led candidate forums leading up to the election, raising issues affecting families and communities.

Candidates in the six Senate districts touching at least a portion of Detroit—1, 2, 3, 6, 8, and 10—were invited to participate. Four candidates showed up to hear and respond to parents. We’ve listed them according to the district they hope to represent in Michigan’s newly drawn map released earlier this year by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC).

Sen. Erika Geiss, D- (District 1), Harry Sawicki, R- (District 2), Sen. Stephanie Chang, D- (District 3), and Sen. Mallory McMorrow, D- (District 8) were in attendance.

The first question came from parent Laquitta Brown whose son struggles with severe asthma. During an attack earlier this year, Brown said he could not receive his treatment at school because of the restrictions on administering quick-release medicine using a nebulizer due to the potential increased risk of COVID-19 transmission. Instead, she had to pick up her son to give him his medication, losing valuable time, she said, where his care was concerned.

Brown’s son is one of tens of thousands of children who struggle with this disease in a city with a higher asthma burden than anywhere in the state. According to a 2021 report released by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS), data collected from 2017 to 2019 shows a significant difference between the prevalence of asthma among children in Detroit (14.6%) compared to Michigan (8.4%). In the same period, hospitalization rates were at least two times higher among Detroit children than Michigan children and three times higher for adults.

Question: What positive changes can you make to school asthma policies so kids can get their life-saving techniques and medications when needed?

Stephanie Chang said the disproportionate impact of asthma and air quality issues on Michigan’s children, Detroit’s in particular, is a big concern to her. She’s never heard of someone being denied treatment because of COVID-19, but she would “dig into that” and thinks it’s something “we should try to work on together.”

“Over the past eight years, I’ve introduced numerous bills around environmental justice and air quality to help lessen the burden, particularly in Detroit, and other communities of color, that have had a disproportionate burden when it comes to air quality,” she said. “Whether it’s the international truck traffic, the steel plants near Downriver, the oil refinery in Southwest Detroit, the Stellantis facility, and their six violations, there’s a lot we can do to ensure we’re addressing the asthma burden in Detroit.”

Mallory McMorrow agreed air quality is a major issue in Michigan. In the state’s shift toward a sustainable future, this has to be equitable across communities, she said. She’s championed legislation that would help schools purchase electric buses, cutting children’s exposure to exhaust. In a situation like this, she said she’d try to collaborate with the parent and the school district to find a solution that supports everybody involved. Her office has often worked one-on-one with constituents to address their specific concerns. Regarding health issues, she said schools need more funding and staff to manage them.

“We know that many of our teachers have classroom sizes that are too large,” she said. “They do not have enough assistance, enough help in the classroom, to work one-on-one, especially with people like your child, to ensure they get access to the asthma care they need when teachers are already overburdened as it is.”

Harry Sawicki said schools are the ones to “set the rules” for this, and he’s concerned with their policies. “All we can do is try to help them,” he said. “I would, first of all, approach this school board about the issue and why this type of situation happened. As to the cause of this, we don’t know what’s causing the asthma attack. But I would like to make sure that your child is properly taken care of at school.”

Erika Geiss said when it comes to improving air quality, we need to ensure that our schools have funding for adequate HVAC systems, HEPA filters, and ventilation for students’ health. She said providing resources for school nurses and school-based health programs is also vital so that qualified people are able and ready to administer life-saving medications and know what protocols to take to protect themselves while protecting students.

“And, to your point about wasting time calling the parent or caregiver to come to the school and administer it; that impacts and interacts with parents who might not have access to paid sick leave or paid time off, or transportation,” she said. “We need to look at each of those things and ensure we are shoring up those areas.”

Question: What can you do at the state level to get commercial trucks off residential streets?

The second question came from Amanda Holiday, a parent living and working in Southwest Detroit. Her Livernois 2 Clark Block Club has been battling against the truck traffic on neighborhood streets in the area. “It’s very frustrating, and the city has been slow responding. There is not actually a city ordinance around truck roads,” she said. “It goes right in with all this asthma and the problems with the air as well.”

Mallory McMorrow said in her last four years representing communities along Woodward Avenue, she’s heard similar concerns about noise and air pollution. She’s seen progress come from collectively discussing issues communities face and working together to see what legislative options are to advocate for at the state level. As a state leader, she couldn’t dictate this directly, she said, so her office holds quarterly meetings with every district mayor, city manager, police, and fire chief.

“I’m proud to say we have put numerous safety measures in place on Woodward Avenue as a result of some of the work we’ve done together,” she said. “That is the approach I would take to an issue like this: how can we work together to see the solutions? Even if the solution is making sure our local leaders are aware of it and able to respond directly.”

Harry Sawicki said he wonders why there aren’t more load restrictions on neighborhood streets.

“That’s something I think individual cities have to look at. On a state level, I don’t know if we can do that much since I’m not an office at this time, but it’s something I could take a look at in the future,” he said. “But I understand your situation, and it’s something I hear. I live two blocks off Telegraph Road, and I know we talk about the noise and the truck traffic.”

Erika Geiss said that though a local issue, intergovernmental conversations with city, county, and state need to happen to ensure restrictions and measures to protect communities living up against truck routes. In her role as Democratic Vice Chair on the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, she’s worked to implement truck weight and speed limits that have come through the legislature. Still, she said, more collaborative conversations and significant action are needed.

“I think public safety and community health need to be the top priority when addressing those traffic issues,” she said.

Stephanie Chang called it “ridiculous” to see commercial trucks on residential streets where families live and play. Her office works to connect and organize residents in the Southwest with those on the east side who also experience negative impacts due to neighborhood truck traffic. She strongly supports the truck route ordinance by Detroit City Council member Gabriella Santiago-Romero, and her predecessor Raquel Castañeda-López.

It’s “a long time coming,” and it has the potential to impact Southwest significantly and, if widened, the city as a whole,” she said. Regarding Detroit’s state and county roads, she said it’s essential to coordinate on all levels to make things “crystal clear.”

“There’s a lot that we can do at the state level to make sure that local policies can be as effective as possible. But we’ve got to work hand-in-hand with them as they develop those policies to make sure that we’re acting appropriately.”

Check out the rest of this series to learn how these candidates responded to more questions from parents around family issues, as well as how Michigan House candidates responded to parents in a September forum. This community conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

This entry is part of our Early Education Matters series, exploring the state of early education and childhood care in our region. Through the generous support of the Southeast Michigan Early Childhood Funders Collaborative (SEMI ECFC), we’ll be reporting on what parents and providers are experiencing right now, what’s working and what’s not, and who is uncovering solutions.