Detroit Future Schools program offers a new classroom paradigm

For the latest installment of our "City Kids" series, David Sands reports on Allied Media Projects' Detroit Future Schools program, which pairs artists with teachers to create a classroom environment where kids can take ownership of their education.

Artists from Detroit Future Schools, a digital media arts program, flip the script when they go into a classroom. In places where traditional teacher-and-textbook instruction are the norm, DFS staff use technology to open classrooms into spaces where students take ownership of their education. To call this a nontraditional approach to supplemental in-school education would be an understatement.

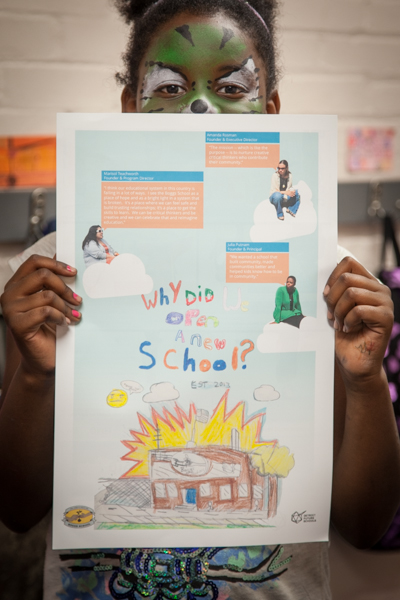

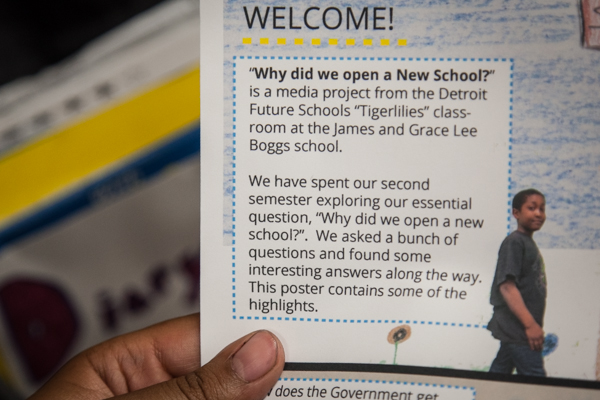

Local classrooms have used Detroit Future Schools tools to create everything from an infographic analyzing why a local charter school opened to a movie exploring what food means to a community.

“We aim to humanize schooling,” explains program director Ammerah Saidi. “What that means is basically grounding the curriculum in real world community problems that the students try to solve by integrating both the curriculum and their real life experiences.”

Over the last three years, Detroit Future Schools has brought its program to over 3,000 students in more than 25 different Metro Detroit schools. These have included second through twelfth grade classrooms in public, charter, and state-run Educational Achievement Authority institutions. Currently DFS is in place at four area “anchor schools” where it’s committed to developing long-term working relationships.

Staff, known as artists, are typically in schools one day each week for three hours. They use that time to turn classrooms into video, audio, and graphic design production studios where youth can draw on their natural creativity and curiosity to look into questions related to a wide range of subjects like math, history, and physics.

Fans of Detroit’s yearly Allied Media Conference (AMC), which offers educational tracks for producing independent media, might be familiar with the DFS’s parent organization. Both AMC and DFS are sponsored by Allied Media Projects (AMP), a nonprofit dedicated to “cultivating media strategies for a more just, creative, and collaborative world.” Detroit Future Schools came on the scene in 2010 when AMP and the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition, another group it helped launch, won a $1.8 million federal Broadband Technologies Opportunity Program grant.

Along with Detroit Future Schools, the money helped fund a media skills training program called Detroit Future Media and a network of leadership programs called Detroit Future Youth. None are connected with the similarly-named Detroit Future City planning initiative.

AMP organizers got their inspiration for Detroit Future Schools after witnessing how media-making could encourage youth leadership. In keeping with the spirit of the grant, the program seeks to increase Internet usage among area youth by encouraging media production.

Resources and Practices

DFS certainly has a lot of tools to help students learn these media skills, including audio recorders, video recorders, cameras, and laptops.

“We bring $150,000 worth of digital media technology to classrooms, and if we don’t have it we buy it,” says Saidi.

Classrooms usually spend the first semester of the year-long program getting a grasp of these media tools and the second developing a media project that focuses on integrating content with community issues.

DFS work begins before the actual school season starts with artist and teacher collaborating on developing a central question for activities, such as: “What does it mean to be human?” and “How is physics relevant to youth growing up in Detroit?” The inquiries are meant to address subject matter and spark students’ curiosity. The formulation of these questions kicks off a year-long partnership between teacher and artist, what DFS calls “co-teaching.”

The relationship isn’t just about letting teachers know the basics of media-making in the classroom, it’s also about exposing them to other elements of the DFS philosophy. These include “critical pedagogy,” which focuses on transforming students from passive observers into active participants in learning persistent documentation and evaluation; and integration of classroom and community through field trips, guest presentations, interviews and hands-on workshops. The end goal is to change how students think about themselves and their relation to the world.

“They’re exposed to a lot of different digital media aspects,” says DFS lead artist Nate Mullen. “Ideally it may turn them on to being a producer of media. But ultimately what they’re walking away with is essential skills they need.”

Specifically, he’s referring to a set of 11 DFS “essential skills” that include collaboration, innovation, and empathy/solidarity. Outlined in the organization’s recently released “Guide to Transformative Education,” they’re aimed at cultivating “ethical agency and interdependence” among students to help them “solve deep-rooted problems, imagine new realities, and build movements that span communities across the world.”

Detroit Future Schools in Motion

The way DFS puts these teachings into practice might discomfit an old-fashioned schoolmarm. It often involves getting teachers to loosen the reigns so youth can take responsibility for their own learning.

A great example of this took place this past school year in a seventh grade science class at Henry Ford Academy School for Creative Studies in Detroit.

Students had to distinguish between two types of plants: monocots and dicots. Rather than explain the differences, students were encouraged to figure out the differences themselves with the teacher sitting back and documenting the process. Initially this resulted in complete chaos, but after a series of investigations the students figured it out. At the end of the semester, the in-house standardized test scores in science shot up 42 percent from an average of about 15 percent.

At Hamtramck High School this past school year, the teacher and DFS artist decided to explore history with ninth grade students from the present backwards, switching out an ancient lesson on the Fertile Crescent in favor of more modern project involving the Cold War. The youth ended up making a movie that included a conversation between cardboard cutouts of JFK and the Chinese Leader Mao Zedong. Performance in the second semester flipped from just five students passing to just five students failing.

Allie Gross, a former fifth grade language arts and social studies teacher at Plymouth Educational Center in Detroit, invited DFS into her classroom after participating in the Detroit Future Media program.

“I feel like my students gained so much. They really looked forward to the DFS artist coming into the classroom,” says Gross. “It really centers upon student-centered learning and students expressing their opinion and backing it up with evidence. Those became key components of my classroom, which I’m very grateful to DFS for introducing to me.”

DFS doesn’t currently have comprehensive quantitative statistics about student performance, but after its inaugural year teachers from many of the 12 original classrooms told the organization they saw increases in student attendance, test scores, and overall engagement.

In a survey of the 2012-13 school year, 28 of 33 students responded that the program “improved their relationship to school and increased their agency as learners.” Twenty-three referred to their DFS artist as a “role model or mentor.”

What’s made these successes possible? According to Saidi, it’s more than just digital tools, it’s the way DFS has put culture over content in the classroom, dealing with students as human beings as opposed to simply drilling lessons in their heads.

“Real learning is fun and engaging,” she says, “And if you’re not having fun, it’s not real learning. That’s what we try to cultivate in our teachers is understanding that once you light that fire it’s a self-fueling fire in the students.”

David Sands is a Detroit-based freelance writer. He’s covered the news for Huffington Post Detroit as an assistant editor and worked as a staff writer for the transportation news site Mode Shift. Follow him on Twitter @dsandsdetroit.

All photos by Marvin Shaouni.

Read about other dynamic people and programs touching the lives of Michigan children and youth at Michigan Nightlight.