Community tech designers forge ahead with Detroit projects

Design Core’s City of Design Challenge invites participants to develop community tech hubs to improve access and opportunity in Detroit neighborhoods. Take a peek at how these three winners are going, and what we can expect from them this year.

Support for ingenuity, creativity, and determination has not waned in Detroit amidst a global pandemic.

This year will see the culmination of investment from three multidisciplinary design teams — Design Core, College for Creative Studies, and Connect 313 — after awarding $60,000 in grant money to advance inclusive community tech hub projects. This was part of the City of Design Challenge which allowed residents of Detroit, designers, and community thought-leaders to brainstorm and collaborate on projects with the goal of improving Detroit neighborhoods.

“The City of Design Challenge lifts up and supports the creative problem solving happening in Detroit neighborhoods every day,” says Olga Stella, Executive Director of Design Core Detroit, and VP of Strategy and Communications at the College for Creative Studies. “The finalist projects are special because they were all sparked in some way by the lived experience of their team members. The Challenge process offered the finalist teams access to design tools and approaches to develop their ideas, especially deepening the inclusion of diverse voices and needs.”

Crosstown Connection

When DaTrice Clark was young, she recalls her great-grandmother taking her on “adventures” on the bus. Clark now understands that those rides were helping her to connect with and explore her community. Therefore, Crosstown Connection has become her “baby.”

“It’s a way I can positively impact the neighborhood I grew up in and help the people out who gave me so much,” she says.

Crosstown Connection pays homage to East Warren, which had the longest bus route in Detroit. In addition to riding the DDOT bus route to the mall with her great-grandmother, Clark also walked to the library on East Warren and Outer Drive, as this was the only place that had internet access. Currently, this facility is still the only free, public WIFI site in the community. Crosstown Connection aims to change that.

Clark, along with Ian Kilpa and Jacob Saphier, is creating Crosstown Connection to serve Detroit’s Morningside Community by closing the gap digitally and literally in connectivity.

The goal of Crosstown Connection is to build community tech hubs, which will function as bus stops along the avenue, allowing people to charge their devices through solar energy, use the hotspot, and read up on what’s happening in the neighborhood.

Clark, who works for an event production company, is determined to see Crosstown Connection come to completion, despite the obstacles experienced.

“The most challenging thing about this project so far has been figuring out who to talk to [in order to] make things happen — from permits to external, reliable WIFI connection,” Clark says.

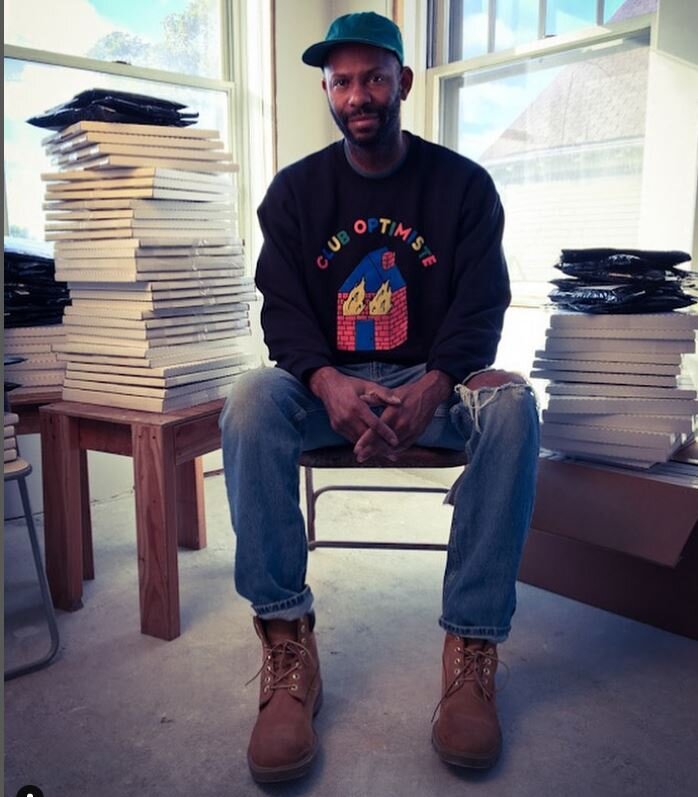

Underground Music Academy

Robert “Waajeed” O’Bryant has 25 years of experience in the music industry and credits the former television show “The Scene” for his passion for music.

Nowhere is this passion more evident than his drive to bring the Underground Music Academy (UMA) to his home city, Detroit.

“Most of my weekends were spent traveling to Europe to spread the gospel about Black music,” he says. “But, after a while, you look around and start to realize no one else looks like you.”

“COVID was the real reminder of the work that needs to be done here [in Detroit]. I had been exporting my expertise to everyone but my own.”

UMA is based on three phases: construction, curriculum development, and opening online. O’Bryant and his team are currently focusing on phase two of content development. Simultaneously creating and maintaining their business model is paramount to extending the longevity and permanence of UMA. O’Bryant understands that there have always been institutions on various levels that are like UMA, which aim to serve the community.

“But none of them stick. None of them stay, and the question is: why?” he asks.

UMA, housed in a 2,400-square-foot building, will serve a minimum of 12 students in person, and extend its robust curriculum online allowing many around the globe to participate. Anyone who is serious about music, whether they are 16 years old or 40 years old, and across all identities, is welcome to be a student at the academy, O’Bryant says.

“UMA is a space for Us first. It’s for anybody different, anyone who has been counted out.”.

UMA’s curriculum will also be based on social justice, something O’Bryant says he has yet to see.

“Not only is it the idea to teach people to be better musicians, better producers, or better DJs, but the spirit is really more about being a more well-rounded person. The planet doesn’t revolve around you, we all got something to learn.”

Although much progress has been made, establishing the academy has not been easy. The need for the existence of a school like UMA is a challenge within itself. O’Bryant often contemplates how to help people reconcile the importance and necessity of the academy. It is a deep-rooted struggle that goes beyond the art of producing music.

“Most folks don’t know that techno is a Detroit-born artform,” he says. “The root of techno and house music is based on peace and love, but in terms of legacy, it’s our birthright as Detroiters.”

18th Street Design-Build Green Tech Hub

Tanya Saldivar-Ali understands the ins and outs of urban planning. 18th Street Design-Build Green Tech Hub is the outward, physical proof of her love of the industry.

Saldivar-Ali and her husband, who are co-founders of AGI construction, aim to have the project on 18th Street give Detroiters the opportunity to learn more about various careers within urban planning and gain access to training through Detroit Future Ops, the social arm of AGI that works on advocating for minorities and local pipelines.

“It is very personal for AGI as Native Detroiters and as a minority business trying to scale amidst a pandemic,” says Saldivar-Ali. “I want people to know that there are many city builders that have been investing and developing our community’s way before the rest of the world decided to believe in rebuilding Detroit.”

Saldivar-Ali has also collaborated with Seann Lewis, a CEO of his own tech company and Navy Veteran, to help with different types of technologies, including matter port scans, VR, and storytelling which is housed on the online portal.

Saldivar-Ali believes Lewis’ passion for VR is what catapulted this project to the next level.

“It was just not the tech but ‘how’ we used the tech that gave access and highlighted the engagement was super innovative, she says. “I realized after COVID hit that we were ahead of the game with tools for our industry and connecting Detroit’s design-built ecosystem with tech innovation.”

But this project is bigger than a building, Saldivar-Ali and her team strongly believe that breaking the generation divide is crucial and involves more than erecting buildings; it stems from ownership of these properties and bridging the digital divide.

“We wanted to demonstrate a community development model that new businesses and other developers could learn from,” she says.

Her teammates share her vision.

“I hope to be able to help people the way I continue to be helped,” says Lewis, who is from Southwest Detroit. “I believe that this project will bring jobs to the area and help those who want to start or maintain their business to do so.”

It’s possible the project would be further along, but accessing capital has been a challenge. Nevertheless, Saldivar-Ali remains laser-focused on the goals of “community engagement, respect, and understanding the needs, trust, solutions by and for the community, and partnerships.”