Data Driven Detroit becomes worker-owned in bid to preserve community-centric culture

What does a worker-owned small business look like? The team behind Data Driven Detroit discuss their new model and why they wanted a democratic, responsibility-driven workplace.

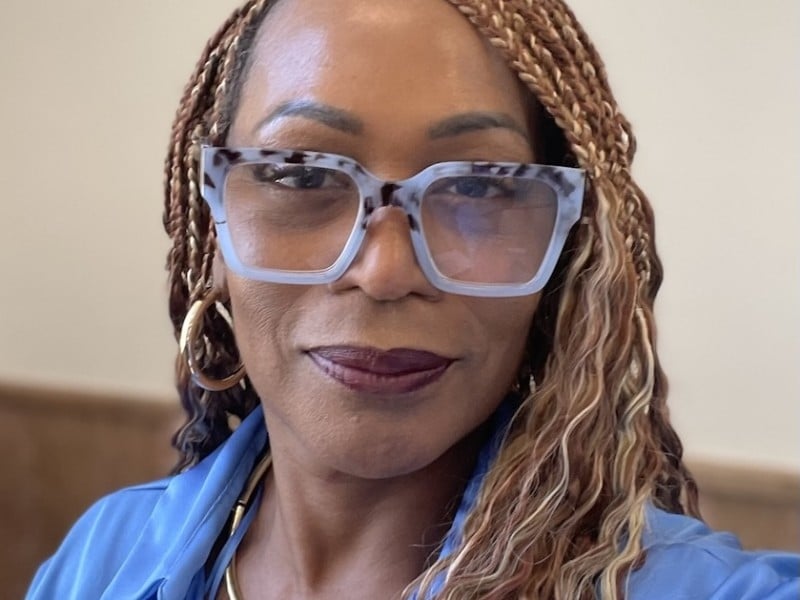

Looking back at a career spent working for other people’s companies, becoming part-owner of a business was something Stephanie Quesnelle never envisioned for herself.

“When I first got married, my husband was talking about starting a company and I vividly remember saying, ‘I never want to own a company,’” Quesnelle, senior research analyst and project lead at Detroit-based data analytics firm Data Driven Detroit, recalls with a laugh.

Quesnelle’s attitude changed in January, though, when the TechTown-based firm transitioned to a worker-owned cooperative — diffusing the responsibilities of ownership among the company’s five owner-eligible employees, including Quesnelle.

As a new worker-owner, Quesnelle says the transition to part-owner of the company where she’s worked for the last half-decade has been a positive learning experience — and a valuable business decision she hopes will help ensure the company’s longevity in Detroit.

“Dispersing that power amongst a group of individuals helps build the stability and long-term sustainability of the organization, which is really important to us because we are a data utility and the longevity of data access in the community — the longer we exist, the more valuable our data is, because there’s more of it,” Quesnelle says.

A history of democratic decision-making

The concept of employee ownership dates back to the mid-1950s, when economist and lawyer Louis O. Kelso created the employee stock ownership plan, a model later explained in “The Capitalist Manifesto,” which Kelso co-authored with philosopher Mortimer J. Adler.

While the ESOP is still the most common structure of employee ownership in the U.S., other models today include the worker-owned cooperative structure employed by D3. According to the National Center for Employee Ownership, a nonprofit advocacy organization, there were 6,482 ESOPs in the U.S. in 2019, accounting for over $1.6 trillion assets. In Detroit, the model has also started to gain traction, with companies like Pingree Detroit embracing the concept in recent years.

According to Noah Urban, co-executive director of D3, the model is something the firm has been moving toward almost since its inception 14 years ago.

“This has been a natural evolution of D3 as an organization, and we’re really excited to be able to present the structure to the world at long last,” Urban says.

Founded in 2008 under the name Detroit-Area Community Information System (D3 changed its name the following year), the data analytics firm became an affiliated program of the Michigan Nonprofit Alliance in 2012, the same year its founding director left the company. Three years later, D3 went independent and transitioned to a Low-Profit Limited Liability Company (L3C) — a structure that allowed the company to maintain its community-centric mission, like the AskD3 program that connects Detroiters with data on request, often for free, while taking on paid consulting projects.

Despite the recent shift to a worker-owned cooperative, Quesnelle says things haven’t changed much at D3. Rather, the transition has been more of a legal formality than an entirely new way of operating.

“[D3 has] always been very focused on collaboration and cooperative decision-making, so the switch to this employee-owner model is really just making that all legal,” Quesnelle says.

To ensure everyone on D3’s 10-person team has a voice, the company employs a detailed decision-making process that gives every team member a seat at the table — a strategy the firm has relied on for years.

“We use a modified form of the sociocracy concept. With sociocracy, one person makes a proposal and the rest of the team discusses the merits of the proposal and voices any concerns that they might have. Once everyone has had a chance to weigh in, the finalized version goes out for consensus. In sequence, each team member has the opportunity to either consent to the proposal as written or offer an amendment, and the process continues until everyone has consented,” Urban explains.

While that process tends to be successful for the team at D3, it isn’t always easy to get people with opposing perspectives on the same page. Although the company’s operating agreement allows for majority votes in specific situations, the option is reserved as a last resort. Instead, Quesnelle says rational conversations and a culture of cooperation prevail in more difficult decision-making conversations.

“It’s not perfect. It might not be the decision you would make in a silo by yourself. That’s part of the process — making sure that everyone’s comfortable with the decision, normalizing those slightly different kinds of ways of running a company and working against a corporate top-down model that people might be used to from other organizations,” Quesnelle says.

New responsibilities bring challenges and growth

Despite the company’s built-in model of inclusiveness, transitioning to a more formal structure of shared ownership wasn’t without challenges for the worker-owners of D3, especially when it came to adjusting to the new responsibilities of business ownership.

“I think all the other worker-owners would agree with me — we’ve all had different experiences, but one of the greatest challenges is the personal growth aspect. Because, aside from Erica (Raleigh, co-executive director), none of us have ever owned a company before, and so learning the ins and outs of that is challenging. But there’s also personal growth that had to happen in order for us to be confident in that transition and in this new role,” Quesnelle says.

One of those challenges, according to Urban, was identifying ways to preserve the company’s long-established values and culture while directing D3 toward a more sustainable future.

“The biggest overall challenge was the fact that we were converting an established organization with, at the time that we started exploring the process, nearly a decade of history and institutional context. That meant that we really needed to be thoughtful with how we designed the new structure, especially with ensuring that would be equitable, in line with D3’s culture and values, and responsive and accountable to the needs of our community,” Urban says.

To achieve that goal, the worker-owners at D3 developed a framework for ownership eligibility that requires a time investment of 1.5 years. After being employed by the company for at least six months, team members can begin the worker-owner curriculum — an educational program designed to preserve D3’s culture and inform future worker-owners about the company’s values and expectations. Upon completion of the year-long curriculum, workers are eligible to be invited into worker-ownership.

“The curriculum focuses on helping people understand how to read financial statements, because we’re in charge of the budget and approving what management brings to us. Understanding the decision-making process — we rely on a kind of modified more form of sociocracy, which is a consent-driven model, so everybody has to agree that that decision is acceptable,” Quesnelle says.

To determine the benefits of ownership at D3, which could include stipends or bonuses but not stock options, Quesnelle says the worker-owner team plans to meet annually to evaluate the company’s performance data.

“Based on our finances and our income and what the projected cash flow for the next year looks like, we’ll be able to decide on an annual basis,” Quesnelle says.

Developing a legacy that will last

Despite its challenges, Quesnelle and Urban agree that the advantages of a worker-owner cooperative model are worth it. In particular, they are optimistic about the model’s ability to preserve the longevity of the company and its culture, especially under future changes in leadership.

“The longevity of D3 now rests on five people, and it’ll soon be hopefully eight, because we have employees who are eligible to start the process to become worker-owners. It kind of diffuses the responsibility across multiple people, so that if any one person leaves the organization, we’re not s**t out of luck,” Quesnelle says, adding that she is also hopeful about the model’s potential for impacting entry-level employment retention — something the data-centric firm expects to evaluate over time.

On a more personal level for Quesnelle, the experience of worker-ownership has driven home the reality of being responsible for the success and continued existence of a company that workers depend on for their livelihood.

“I think that it helps us all appreciate the work that the executive directors put into the organization to keep us employed, because that’s a big part of their job is to continue getting us new projects. And being on the frontlines of that, we kind of all have to appreciate each other’s role in the organization a little bit more,” Quesnelle says.