Detroit author turns son’s reading challenges into hope for kids across Michigan

Leslie Vaughn’s ‘Bus Stop Blues’ gives struggling Detroit readers a story that reflects their challenges and offers a way forward.

Leslie Vaughn was lost and looking for options. A former teacher at Oakland University, she left the job to homeschool her children. Seven of them were strong readers, but her youngest son was struggling.

Knowing this was something she could not handle herself, she and her husband put him in school in the second grade. Three years later, in fifth grade, her son was getting good grades, was well-behaved, and participated in class. However, he was still struggling with reading, and she was afraid he had missed the window.

Fourth grade is considered a crucial stage for reading development because it is the grade at which most students transition from learning to read to reading to learn. As reading becomes a bigger part of the educational process, students who struggle with reading fall further behind.

“If they are not proficient by fourth grade, they are not proficient readers,” said Kristin Dwyer, founder and executive director of We Shall Read, a nonprofit that focuses on expanding literacy by teaching others how to teach people to read.

According to the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), 65 percent of American fourth graders read below reading level. Michigan is struggling more than most, ranking 44th nationally in fourth-grade literacy.

If children are the future, Michigan’s current literacy scores are a flashing red light about tomorrow’s danger.

“Teachers choose the level they want to teach,” says Vaughn, pointing out that most teachers after fourth grade are not equipped to teach kids to read.

Like many parents who homeschool their children, Vaughn belonged to a co-op. There she met Dwyer, who told her there is only one way the brain learns to read, which is through phonics. She became Vaughn’s son’s tutor and also taught Vaughn how to better help her son improve his reading skills.

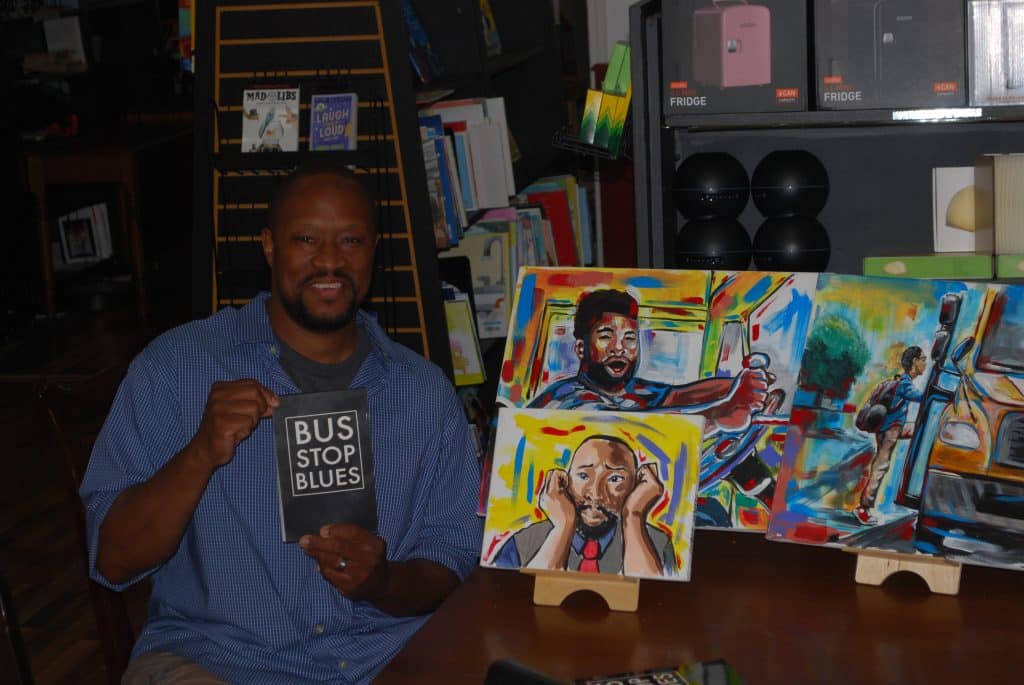

While helping her son, Vaughn couldn’t find a book that matched the emotional and interest level of older students struggling with reading after the fourth grade, so she wrote her own book.

Bus Stop Blues engages older readers by first using buses as a symbol for doing well in school and succeeding in life. In the book, the main character misses the bus and finds himself falling further behind in school.

In Bus Stop Blues, the main character is a young boy who compares his difficulties with reading to waiting for a bus that just passes him by.

Vaughn writes: “It is like I am at a bus stop. The bus goes by but does not stop. It does not stop. Why? I was at the stop. I yell and yell. I run and run. I huff and puff. I jump and cuss. But I am left. Why?? I was at the stop!?

The boy’s damaged self-esteem is highlighted in the book. He feels like he will never catch up, wondering why he struggles when reading comes so easily to friends, and how he deals with the feelings, like breaking pencils to distract himself from his poor reading skills.

Flashy black cars representing the criminal element illustrate what can happen to young, struggling kids looking for an easy way out. As the book says, “They come to the bus stop and wait for kids to quit. Then they pick them off one by one. They use them up and spit them out and come back for more.” According to the Department of Justice, 85 percent of juvenile offenders struggle with reading.

Vaughn’s book makes struggling readers see they are not the only ones invested in their success and confronts the struggles of intergenerational literacy problems. It gets inside the head of the main character’s mother, who remembers her own reading struggle as a student. She would break pencils and be a disciplinary problem, so no one would notice she was struggling, just like her son. As a result, the mother wants to help her son but feels powerless.

Parents who struggled with reading themselves want their children to succeed, but many may not have the skills to help and are too embarrassed to admit they have an issue.

Books aimed at helping older students improve their reading skills must connect with that age level, says Dwyer. Many primary reading books are geared toward early elementary school-age kids. A kindergartener’s book, like See, Spot, Run, will not engage an older reader.

“Older readers will reject books that seem too babyish,” she says.

Vaughn recently launched her book, Bus Stop Blues, at Pages Bookshop in Rosedale Park, where a roundtable was held after the book was read.

Dwyer was one of the participants. Again, she emphasized the need to learn phonics to be a strong reader. She said attempts to teach outside phonics can have negative effects on readers because, moving forward, their brains will make a partial or wrong connection to the word.

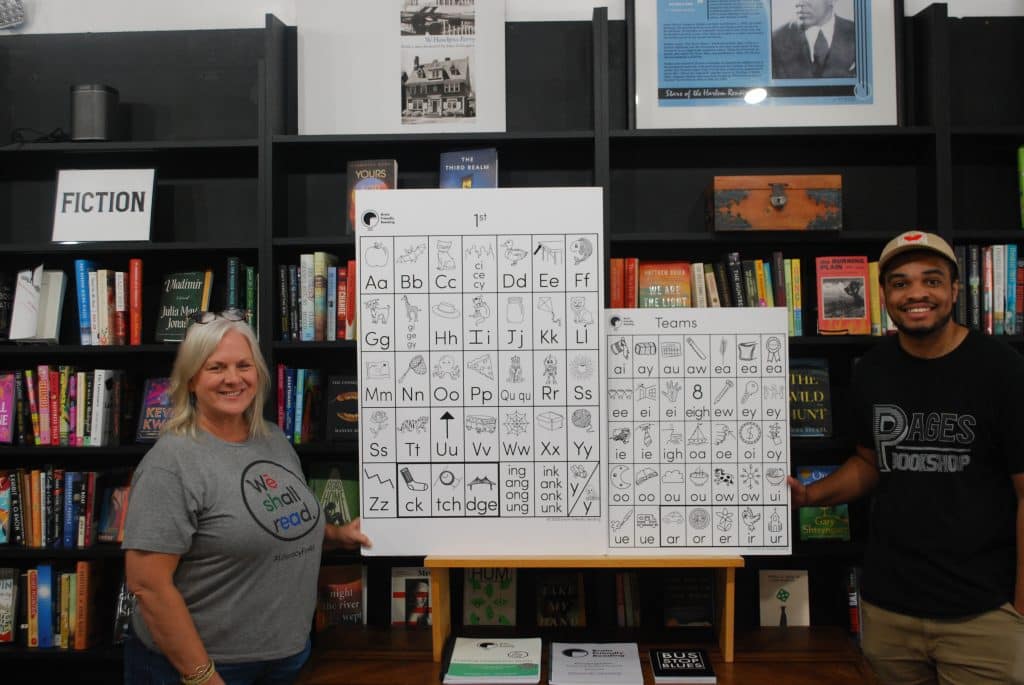

To help teachers better teach reading, she was a part of a team that created the Brain-Friendly Reading program. She used how she taught Vaughn to teach her son as a pilot for the program.

Today, Vaughn’s son is not blazing through copies of Moby Dick, but he is doing better. He can read recipes and is now rereading books and getting a better grasp on their content.

Dwyer has successfully taught phonics to older struggling readers. One 16-year-old student is now able to take his written driving test. However, she notes that while all brains learn to read the same, all brains are different, and the process will take longer for some.

Her most successful program helping teachers to teach has been in South Redford, where they were very receptive and wanted to find better ways to teach. Dwyer said she also reached out to the Pontiac school system and found they were not interested.

She uses a phonics sound chart to help struggling readers learn the letter sounds in a rhythmic way that engages them. The goal is to have them retrieve the sound by sight. An example of how it can be used to teach children can be found here. The same chart is in the back of Vaughn’s book.

When asked for other suggestions on how to improve reading skills, roundtable participants said parents need to read more to their children, and giving them books on topics they like or having friends read to them would be helpful.

According to Dwyer, just pushing kids with topics or peer pressure would not help them learn to read. Once they have had their explosive reading moment, it could be a way to strengthen reading skills or make them more invested in improving those skills. However, if they are still struggling, they will struggle without the phonics build-up.

The roundtable also included a discussion about the different types of reading that come with changing technology and the need to bridge gaps. New technology like Twitter and texting has created new, faster ways of reading, and in some ways a new language.

Several in attendance had a history in education and appreciated how the book looks at the frustration of teachers, who want to help kids read, but can’t. Many teachers are discouraged and internalize their inability to help struggling readers.

In her book, Vaughn casts teachers as bus drivers, driving the kids to adulthood.

“We are good drivers,” writes Vaughn in her book. “Yes, but what good is a driver if the bus is broken?“ Followed a few lines later by “we are drivers, not mechanics.”

She also pointed out what she sees as flaws in the system.

One problem is how reading progress is tracked. The reading levels of grades, teachers, and districts are tracked by year. However, the progress of the individual student is recorded, but not tracked, so there is no record that shows if that student is getting better, stagnating, or getting worse.

Today, there is a good model for improving reading. After decades of being at the bottom of reading scores nationally, Mississippi enacted what has been dubbed “The Mississippi Miracle.” Today, the state is in the top quartile.

The Literacy-Based Promotion Act, passed in 2013, involves much of what Dwyer and Vaughn advocate and experience. It mandates phonics-based science of reading instruction and teacher training in the science, reading coaches, holding back third graders who don’t meet reading standards, and early testing to improve students’ reading skills and comprehension.

Dwyer believes a massive call for reform is needed on the state level to enact the policies in Michigan or anywhere. However, this would not do anything about the students struggling with reading, and a separate plan would be required.

“Nobody doesn’t want these kids to read,” is Vaughn’s mantra. The question for Detroit and Michigan is, why can’t they?