How good teachers are making a difference in Metro Detroit’s multiethnic classrooms

American students are more racially and ethnically diverse than ever before. Thats why teachers in multiethnic communities are responding by developing more inclusive curriculums.

At Kosciuszko Middle School in Hamtramck, at least seven different languages are spoken by students, whose ethnic backgrounds include Yemeni, Bengali, Bosnian, Albanian, Polish, and Lebanese. While this may not be your typical American school, it is a microcosm of the multiethnic city of Hamtramck, home to the country’s first Muslim majority city council.

Americans are more racially and ethnically diverse than ever before. Much of this change has been driven by immigration—it is estimated that 14 percent of the country’s population is foreign-born, and this number is expected to continue to grow. How are schools and teachers adapting to these changing demographics? When much of today’s political rhetoric on immigration is negative, immigrants and second-generation students are facing unique challenges in the classroom.

Teachers in multiethnic communities like Hamtramck, Dearborn, and Southwest Detroit are responding by developing more inclusive curriculums, teaching empathy and an understanding of other cultures, and engaging students in political discourse and community-based action.

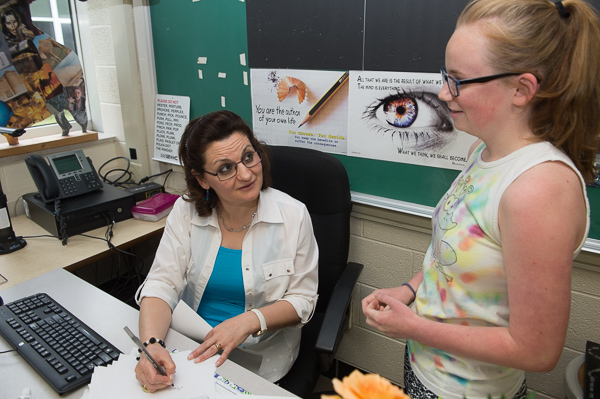

Nancy Walter, Kosciuszko Middle School

At Kosciuszko Middle School in Hamtramck, most of Nancy Walter’s students are immigrants from Yemen and Bangladesh. Kosciuszko’s student body includes approximately one-third Yemeni students, one-third Bangladeshi students, as well as Black, Bosnian, and Central European students. One fourth of the school’s students speak English as a second language.

Walter, who is fluent in Bengali, is an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher. But language is hardly the only challenge.

“Our kids are crossing a huge cultural, religious, and language gulf,” says Walter. “It’s important to acknowledge who they are, and one of the biggest challenges is finding materials that really reach our kids.”

Because nearly 80 percent of ESL students in the U.S. are Spanish-speaking, much of the curriculum is designed for that demographic. But when it comes to students like hers, who speak Arabic and Bengali, Walter has few easily accessible, culturally relevant resources. She seeks out books and other resources that connect with her students’ cultures, such as watching stories from “Arabian Nights” when studying Islam or playing carrom, a game popular in the Middle East and South Asia, at lunchtime during Ramadan.

Empowering students to feel proud and connected to their cultures is important for Walter, who recently organized a series of day-long events for the ESL students at Kosciuszko to celebrate their cultures. The first was held on February 21, overlapping with International Mother Language Day, a holiday widely celebrated in Bangladesh. ESL students decorated the school with their national flags, made posters in their mother tongues, served home cooked food, and dressed in national dress. Teachers were invited to share a meal and learn more about their students’ home countries.

“Learning a language can make you feel dumb,” says Walter. “Having a day to celebrate their cultures and allowing them to be the experts in something is very motivating for our ESL students.”

This was the first year Walter organized cultural celebration days, and she hopes to make it a school wide celebration next year.

In addition to navigating the cultural differences of being a first generation American, Walter’s students must also confront the very real threats they face as immigrants. “Half of my students are from Yemen—one of the countries on the travel ban,” Walter says. “The fact is they fear going home for the summer, and they ask me, ‘Will I still be able to get back into the U.S.?'”

In February this year, Kosciuszko Middle School’s board passed a motion declaring themselves a “Safe Haven” school that will not cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids or seek students’ immigration status.

Walter’s goal is not only to help her students feel pride for their own cultures, but also to learn empathy and understanding for people different from them. To this end, she started a language exchange unit with her Bengali and Yemeni students so each group could teach the other their mother tongues. She also recently partnered with a group called Religious Journeys to launch a series of field trips where the kids visit a mosque, Hindu temple, Sikh temple, and the Holocaust Memorial Center.

“Someday they may not have all Bangla and Yemeni neighbors,” says Walter. “If I can give them the skills to get along with anybody I’ve given them something that will help them move forward in their lives.”

Lisa Lipscomb-Jones, Neinas Dual Language Academy

At Neinas Dual Language Academy in Southwest Detroit, a pre-kindergarten to eighth grade public school, almost all of Lisa Lipscomb-Jones’ students are Hispanic, first or second generation Americans, from countries such as Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Panama.

For some of her students, school is the only place where they speak English, and keeping up with state mandated testing can be a challenge. “Our kids are burned out from hours of testing,” says Lipscomb-Jones. “And because they’re doing it in English, it’s not always an accurate reflection of what they know.”

She tries to tap into the general interests of her students to engage them. For example, she recently assigned one of her students to be the class photographer after she learned he had taken photography classes. “When kids see I’m interested in their life, not just doing my job, it makes a huge difference,” she says.

In recent months, several families have left the community because of a fear of deportation amidst increased enforcement of illegal immigration and an anti-immigrant political climate. “Often the kids may be here legally, but their parents or caretakers are not,” says Lipscomb-Jones.

The school has Spanish-speaking secretaries and hosted a number of trainings around immigrant rights and resources to resist deportation. Lipscomb-Jones also uses journaling as a way to help students process what they are going through, providing open-ended prompts for students who, she says, “feel like they need to vent.”

Place-based learning is another important component of her classroom, something she developed through her experience with the Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition (SEMIS Coalition), a program at Eastern Michigan University that partners with schools to empower students to create positive change in their communities. A few years ago, Lipscomb-Jones took her students on a community walk with the program, where they examined things in their neighborhood that they’d like to change, such as the abandoned, burned-out building across from the school. The school’s science teacher, Amy Lazarowicz, worked with the students to create models designing their visions for the space.

The building was eventually demolished and the space will be transformed into a soccer field and learning center. “I feel that it’s my job to empower them to know how to write a letter, make a phone call, imagine another way—rather than saying that this is the way it is,” says Lipscomb-Jones.

Amira Kassem, Dearborn High School

Amira Kassem has been teaching in Dearborn for 25 years. Currently she’s a ninth grade English teacher at Dearborn High School, which has a student body of approximately 2,100, 50 percent of whom are Arab American, and 25 percent English language learners.

“Historically, Dearborn High has been a mostly white, middle class school,” says Kassem. “We see that shifting, not only with more students of different ethnicities, but also students of lower socioeconomic backgrounds.”

English language learners, or students who speak english as a second language, are the fastest growing population at the school. But it’s been a struggle to find teachers willing to teach ELL classes. “There’s a deficit mindset towards these students,” Kassem says. “A view that if you’re working with a minority population they are somehow less.”

In her English classes, Kassem uses literature as a means of an “investigation into the self.” Kassem recently introduced the idea of slam poetry to the students, bringing in Black and Muslim poets to share their work on issues like discrimination and mental health. “Slam poetry appeals to the students because of its performative nature,” says Kassem. “The pain is on display, and it’s very sincere and transparent.”

At the end of the unit, one of her students shared a poem she had written that involved her coming out as gay for the first time. “She had been silent about it until that moment,” says Kassem. “On paper she is a very high achieving student, and you never would have known about her struggles and mental health issues.”

Some of her students also formed a Modern Discussions Club, where they come together after school to debate issues like mental health, prejudice, racism, the recent presidential election, and terrorism. Based on their interest, Kassem is teaching a social issues class next year—the very first at the school.

She plans to teach the history of the civil rights movement in the United States and facilitate a project in which students engage actively in a social justice issue. “They learned that to speak about politics is wrong,” says Kassem. “My role is to engage kids in critical thinking and facilitate discussion. They need to unlearn this idea that teachers need to tell them what to think.”

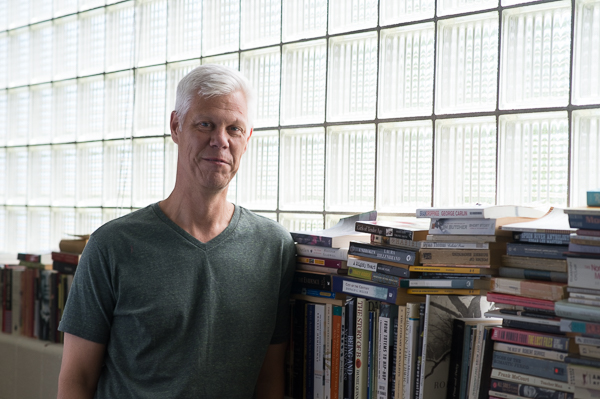

Rick Kreinbring, Avondale High School

The fastest growing population in the school district of Auburn Hills is people whose second language is English, including primarily Hispanic and Asian immigrants—close to 17 percent of the population in Auburn Hills is foreign born. For Oakland County, a predominantly white region of Metro Detroit, Avondale High School’s student body is relatively diverse, with 20 percent African American students, and 15 percent Hispanic and Asian.

Rick Kreinbring has been an English teacher at Avondale for 26 years, and has witnessed the demographic shifts. “When I first started teaching AP classes the curriculum looked like ‘Rick’s favorite books,'” says Kreinbring. “That’s fine if I’m teaching white boys from 1983, but my evolution in the classroom was first to stop picking so many white dudes, and then realizing I needed to pick writers of color and women because that’s what my class looks like.”

Kreinbring participated in a writing workshop with the National Writing Project around the topic of creating a culturally responsive classroom and realized he needed to address the demographic changes he was seeing in his school through his classroom curriculum.

So Kreinbring swapped “Death of a Salesman” for “Fences,” and chose texts that focus on protest and the use of force by police. “It has to be about them, not about us being uncomfortable,” says Kreinbring.

After reading “Fences,” “students were a thousand times more engaged,” says Kreinbring. From his perspective, the themes between that book and “Death of a Salesman” are very similar, but through changing the language and the setting, it becomes much more relevant to kids’ lived experiences.

Over the summer, Kreinbring assigned “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lax” and “Between the World and Me,” books that address issues of race and culture. As much as these changes engage his students of color, he says it’s also about “providing white kids with a look at something other than themselves.”

Beyond diversifying the texts in his curriculum, Kreinbring’s larger focus is on teaching argumentative writing skills that help his students better express their opinions. “Access to these skills means that you have access to democracy—the ability to be literate, argue effectively, defend yourself. That’s huge. That’s your way into the conversation.”

This article is part of Michigan Nightlight, a series of stories about the programs and people that positively impact the lives of Michigan kids. It is made possible with funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Read more in the series here.

All photos by Sean Work.