How Detroit’s climate change activists are using science to plan for a warmer city

As Detroit's climate changes, scientists are working to inform policies that will help the city both mitigate its greenhouse gas emissions and increase its resiliency in the face of a warmer, wetter future.

Imagine Detroit circa 1950. Men in dark suits and fedoras dash in and out of high-rise buildings. Women in dresses and heels shop at the downtown Kresge for home linens and cosmetics. Streetcars crowd Woodward Avenue alongside shiny Studebakers, Cadillacs and Packard Super Eights.

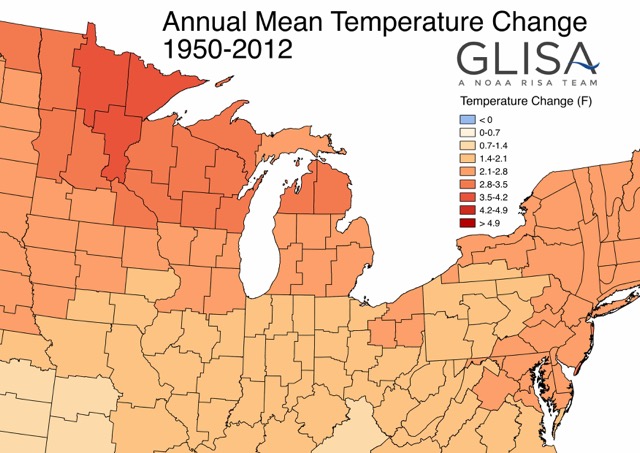

And the climate was approximately 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit cooler on average than it is today.

That’s according to historical climate data analysis from the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program (GLISA), a collaboration between the University of Michigan and Michigan State University. It’s funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and is one of a network of Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISAs) that focus on local climate change adaptation.

GLISA focuses on the Great Lakes, working with cities and rural communities to support efforts to plan for climate change. But rather than focusing on how the climate might change in the next century, GLISA uses historical weather data to look at how it’s changed up to now.

“In our experience, we’ve found bringing people information about how climate has already changed has been really valuable, because many of times people don’t even realize the changes that they’ve already experienced,” says GLISA climatologist Laura Briley.

According to GLISA’s analysis, most of the warming in the Detroit area so far has been in winter and spring. Metro Detroit has experienced increasing precipitation during all seasons. Total precipitation has increased thirty percent in the fall. And much of the warming has come from increased daily low temperatures.

“That becomes really important in the summer,” says Briley. “Those nighttime low temperatures help people get relief from the heat. That relief has been harder to get and will continue to be harder to get into the future.”

This kind of local scientific insight is helping Detroit’s climate activists develop plans to cope with climate change in the future.

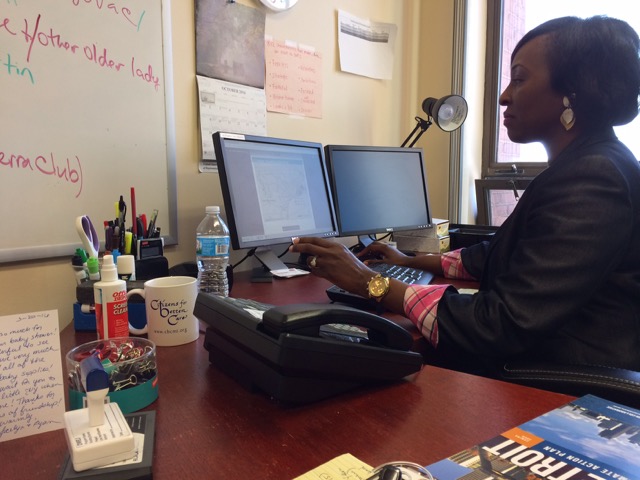

Kimberly Hill Knott is the director of policy with Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice.The group is leading a Detroit Climate Action Collaborative of 25 public and private partners to develop a climate action plan for Detroit. They’re relying on scientific data and models from GLISA and the University of Michigan to inform the strategies and policy recommendations in the plan, which is expected to be released later this year.

“We’re using this information to develop a more targeted approach in our recommendations,” says Knott. “For instance, when considering green infrastructure or energy usage reduction projects, we’re incorporating information from the climatology report, developed by GLISA, in addition to our maps that show the areas of greatest climate vulnerability. So instead of planting trees everywhere for aesthetic purposes, we’re looking at the areas that are most prone to climate threats.”

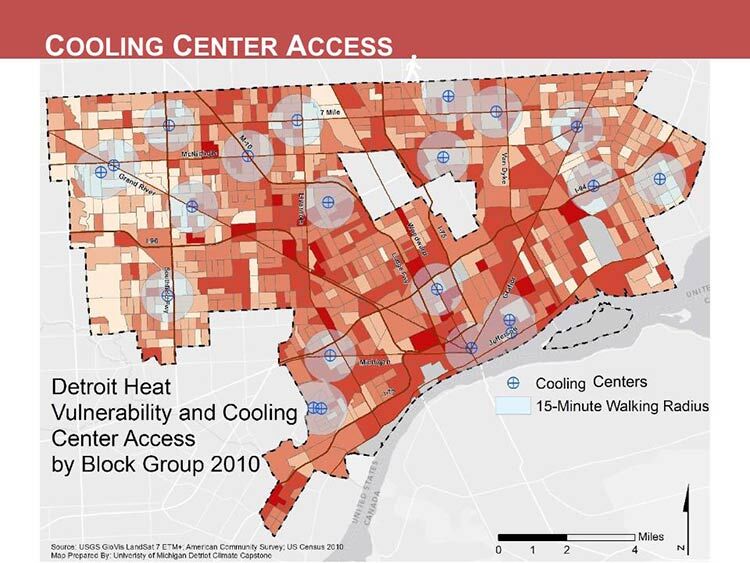

That kind of analysis applies to many facets of climate change planning and adaptation. A University of Michigan analysis identified the areas of the city with the greatest heat vulnerability. They first identified the hottest areas of the city by combining surface temperature data with measures of impervious surface, like trees and vegetation, which have a cooling effect. The researchers then combined and mapped demographic data describing vulnerability to heat-related illness, including the proportion of residents 65 years and older, educational attainment, poverty, and household access to a vehicle. The end result was overlain on a map of cooling centers to show gaps where they were most needed.

“Hopefully city planners can use this information to make better decisions about where you might place cooling centers and how long to keep them open, since many places tend to be places like libraries,” says Larissa Larsen, an associate professor in the Urban and Regional Planning Program at the University of Michigan who supervised the work.

Once the plan is complete, an implementation phase will begin. But it’s not simply a matter of enacting a few initiatives or programs. Addressing problems like this, and climate change generally, will require complete buy-in across all sectors of the city.

“We believe that effectively addressing climate change will require an all hands on deck approach,” says Knott. “There’s a role for everyone—for city government, for local government, for residents, for businesses and institutions, and the public health sector.”

To engage residents, the group is working through Detroit Climate Ambassadors Program to empower people to make a difference in their own neighborhoods. The Ambassadors are currently working with residents in the flood-prone Jefferson-Chalmers area on a “train the trainer” program to install rain barrels and rain gardens throughout the community.

Another important issue addressed in the plan is energy poverty. Tony Reames is an assistant professor in the School of Natural Resources and Environment at the University of Michigan and leads the Urban Energy Justice Research Group. His work in Kansas City, Missouri and Detroit shows that households in areas with concentrated disadvantage also experience energy poverty; they tend to live in inefficient buildings and pay a disproportionate amount of their income on energy, known as the energy burden, especially when compared with higher-resourced areas. An affordable energy burden for heating and cooling is four percent or less.

“It’s a justice issue,” Reames says. “People with higher energy burdens are less resilient to climate change because they have fewer resources to adapt to extreme temperatures.”

Reames proposes programs that help improve energy efficiency targeting energy poor neighborhoods. He points to Kansas City’s “Green Impact Zone” programs which proactively funneled resources into weatherization and energy technology in low-income, high vulnerability neighborhoods.

“This can improve the resiliency of low-income neighborhoods while also creating training and jobs for the people in those neighborhoods,” he says.

By 2050, a full century will have passed since men in Fedoras, women in heels and Packards traveled on Woodward Avenue. Those of us who will be fortunate enough to be alive then are likely to see a much transformed Detroit—one that we hope is more vibrant, perhaps yet again with a streetcar running on Woodward.

That Detroit will almost certainly be warmer and wetter. But because of climate science and the planners and activists putting that science to work, it may be well be a greener and more sustainable city as well.

This piece is part of a series highlighting the role science plays in Detroit. It is supported by the Michigan Science Center.

All photos, except of Kimberly Hill Knott, by Sean Work.