‘Keep Detroit weird’ and other takeaways from second Detroit-Berlin Connection conference

The second-annual Detroit-Berlin Connection conference began by redefining what "techno" is and ended with a declaration that "we must keep Detroit weird."

It began by redefining what “techno” is and ended with a declaration that “we must keep Detroit weird.” In between, there were four hours of presentations, discussions, slides, and marketing strategies to promote “subcultural” assets and develop the city’s “night economy.”

The second Detroit-Berlin Connection conference, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) last Wednesday, offered outside-the-box ideas and actions to move Detroit forward. There were no heady monologues steeped in obscure theory. It was a solutions-based conference based around Detroit inspiration and simple ideas that work in Berlin.

“Detroit must be open all night –for thinkers, philosophers, for innovators and problem solvers, for locals and travelers from afar,” said Dimitri Hegemann, founder of the Tresor club and label in Berlin.

Berlin, one of Europe’s most dynamic cities where tens of thousands of visitors come for art and music events every weekend, “would collapse” if it closed down at 2 a.m., said Hegemann. His words were echoed by Burkhard Kieker from Visit Berlin, which markets the capital city as a place where alternative cultural options — including intense clubbing that lasts from Friday to Tuesday in some spots — are the main attractions.

Hegemann was joined in conversation by Packard Plant owner Fernando Palazuelo, with whom he is hoping to partner in a major “art project-based” redevelopment of the former Fisher Body 21 plant. (Though no announcement of a formal partnership was made, Hegemann said after the conference that he believes he and Palazuelo can work together on a project at the nearly 600,000-square-foot building in the city’s Milwaukee Junction.)

Other highlights included a presentation by University of Detroit Mercy School of Architecture faculty members Tadd Heidgerken and Noah Resnick, who are heading a summer studio dedicated to finding new visions for Fisher Body. There was a panel on repurposing industrial spaces and a presentation by Philip Kafka, who owns a New York City-based boutique advertising company called Prince Media, which is behind Move to Detroit billboards in Brooklyn.

Galapagos Art Space director Robert Elmes, who was to appear with Kafka on a panel to discuss their investments in Detroit and Highland Park, did not attend the conference due to illness in his family.

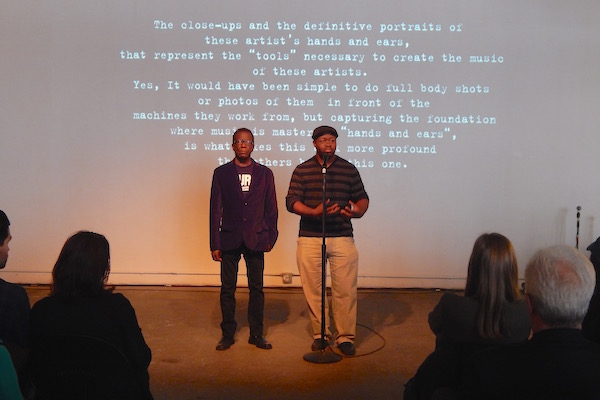

The conference got its techno bearings (though the project is far more than about music, Hegemann said) early by featuring a slideshow of Detroit artists by Berlin-based photographer Marie Staggat. John Collins and Cornelius Harris of Underground Resistance then put techno into the context of the project by saying it was “about the future,” as much to do with high speed rail from Detroit to Chicago as it is about dancing to 4/4 beats.

Marsha Philpot (aka Marsha Music) added perspective to the future by talking about the past — in particular the now demolished Hastings Street commercial strip that was home to a thriving African-American performing arts district. The roots of techno, it can be argued — of all Detroit black music in fact — are here, replaced by a ditch that carries motor traffic up and down I-75 and I-375, between Milwaukee Junction and downtown.

The mood throughout the entire conference was upbeat, but the energy became kinetic as it moved to its conclusion.

Lutz Leichsenring of Club Commission Berlin teamed up with Kieker of Visit Berlin to talk about the virtues of their city’s “scene economy” or night economy, describing the benefits of attracting millions of young people from Europe and around the world. Berlin is largely absent of all the industry and manufacturing that drove its economy in the first half of the 20th century, replaced by a service economy led by record-setting tourism. In 2014, nearly 29 million overnight stays were recorded in Berlin, about half that number coming for alternative arts and culture programming, Leichsenring and Kieker said.

During the Q&A session, a man in the audience asked if the goals of the Detroit-Berlin Connection included persuading billionaire investors like Dan Gilbert to think about strategic alternative culture options for his properties.

Panelist Mario Husten, who is behind Holzmarkt, a cooperative urban village being developed on the banks of the Spree River that cuts through Berlin, answered by saying, “Creativity cannot be bought.”

Hegemann said he has not yet met Gilbert, but he would like to. “We must say to him that Detroit must stay weird,” he said. “It is an inspiration for Berlin. We don’t want to change too much. Just get some brooms and clean it up. Bring people to visit and to live here. This is our plan.”

Walter Wasacz is former managing editor at Model D and fully discloses that he now consults for the Detroit-Berlin Connection. His notes, however, remain as pure as his Detroit soul.